The Graves on ul. Kawia

by WIESŁAW PASZKOWSKI, Częstochowa Municipal Museum, History Documentation Centre

Edited: ALON GOLDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel English translation: ANDREW RAJCHER

On the night of 21st September 1942, German police (under the command of Hauptmann Schutzpolizei Paul Degenhardt, supported by armed formations) surrounded the Częstochowa ghetto and began a full isolation of the area. The deportation to the extermination camp was also accompanied by a large number of additional deaths, as the death penalty was also the result of any attempt at resistance, hiding or escape.

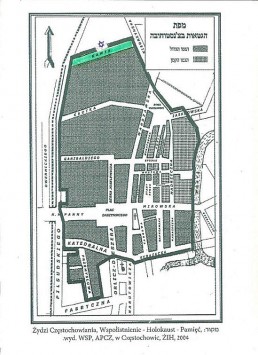

This meant that there was a need to bury those murdered within the confines of the blockade. The Germans selected vacant land at ul. Kawia 20 and 22 for this purpose, right near the northern border of the Częstochowa ghetto. According to Jewish historian Liber Brener, the author of Widersztand un umkum in czenstochower geto, before the commencement of the deportation, the Schutzpolizei had removed all the Jews from the area and, on the first day of the aktion, 22nd September 1942, the removal and burial of all the murdered corpses began.

The Germans brought (…) an older member from the Chevra Kadisha, Miśka, who was, under the supervision of the military policeman Überschär, to manage the collection of those killed and the transportation of them to ulica Kawia, where two mass-graves had already been prepared.

Hauptmann Degenhardt assured Miśka that he would be completely safe if he carried out this task well. He also allocated him an apartment on the grounds of the former “Metalurgia” foundry on ul. Krótka. Miśka was provided with carts, formerly owned by Jewish butchers and which had been used to transport animal carcasses. They were covered with timber planks which rose from the sides of the carts.

Janusz Czaryski described, in detail, the beginnings of the work carried out on that day on ul. Kawia:

At lunchtime, the Volksdeutsche Blanke (…) told us that he had been ordered to take us to “Metalurgia”. When we arrived there, that thug Degenhardt told us to run to the gate, where the Germans were already standing. He then carried out a selection, beating the Jews.

At the gate, a policeman approached me and told me to go outside. There was a group of seventy men there and the military policeman led us to ulica Kawia. Another policeman on horseback took over the group and said that we were to work. The tools were already in place.

Half of the men began digging graves, while the others stacked corpses. The military policeman said that we should carry out the work “anständig” (decently). If not, there was still room enough there for all of us.

The horror was indescribable when we saw the carts, which once transported meat, bring the dead bodies of the murdered Jewish victims. We laid the bodies into the graves in rows, head to head. After each row (layer) was laid, we poured in lime or chlorine.

We have no eye-witness description of what happened on Kawia over the following days.

Brener’s book contains a description based on post-War reports by non-Jewish residents:

The wagons, containing the dead, rolled along ulica Kawia, where the Schutzpolizei pulled gold teeth out of the corpses and cut off fingers with gold rings. These were collected into baskets and taken away. The elderly, the sick and children were also brought here. They were forced to undress and lie in a row, face down. It was only then that the military policemen went from one victim to the other, shooting each of them in the head. Later, some of the clothing was given out to residents of the street who had, earlier, been forced to throw the corpses into a mass grave.

So, the graves on ulica Kawia also became a place of murder.

Deportation trains left for the Treblinka extermination camp every three days. But, in the intervening two days, German police, assisted by auxiliary units, searched empty homes, pillaging abandoned possessions and murdering the Jews in hiding. This was why, every day, wagons brought corpses until the end of the aktion. The last transport was arranged for 7th October 1942. At that time, Degenhardt summoned Miśka and his wife and sent them to the wagons. Responding to Miśka’s complaints, he said that an officer’s word to a Jew was meaningless.

The group of wagon-drivers and gravediggers, led by Miśka, had transported 1,600 individuals to be murdered at ulica Kawia. After the War, it was reported that at least 2,000 had been murdered there. So, at least, four hundred Jews had been killed on the spot.

In Degenhardt’s post-War trial, the indictment accused him of the murder of twenty sick Jews in October 1942. They were forced labourers who were extracted, after selections, from HASAG-Pelcery. There, they had been diagnosed with some sort of disease. Due to the extremely poor sanitary conditions there (workers slept in their clothes on a concrete floor, with limited access to water and sanitation), there was a fear of an epidemic break-out. Degenhardt ordered all the sick to be brought to ulica Kawia. A pit had been dug there. Degenhardt ordered the sick to run around the grave. He took a machine-gun from a factory guard and, with one rain of bullets, he killed them all. After hearing from an expert, the court in Lüneburg considered it to be technically feasible and also found the testimony of two eye-witnesses to the murders to be credible.

Initially, the graves were cared for by the Częstochowa District Jewish Committee. The graves were surrounded with metal mesh. There were two concrete slabs, containing inscriptions in both Polish and Yiddish:

Mass Graves of

Jews

The Victims of Nazism

22nd September 1942

May their memory be honoured.

(The right grave inscription is in both Yiddish and Polish. The left grave inscription only in Polish.)

Caring for the graves proved difficult, because the area was privately owned. The municipal authorities wanted to have the bodies exhumed, because they were afraid of an epidemic (the graves were located close to residences, next to where potatoes were being grown).

Unable to cope with its obligations, the Częstochowa District Jewish Committee handed the graves over to the Częstochowa authorities who, in turn, passed care on to the Zieleń Miejska company. After its transformation into the Municipal Public Utilities Enterprise, it continued to care for the graves. It is known that, in 1962, the graves were cleaned up. Lawns were planted over the graves and roses were planted. Concrete pavers were laid at the graves and a hedge was planted along the fence. After that, care and repair were carried out on a regular basis. For example, in 1982, the surface of the paver slabs was repaired and the fence mesh was replaced. The current cast iron surround was, most probably, installed in the 1990’s.

The complex consists of two graves measuring 36.0 x 4.5 = 162 sq.m. and 33.0 x 9.0 = 297 sq.m.. The whole area measures 661 sq.m.

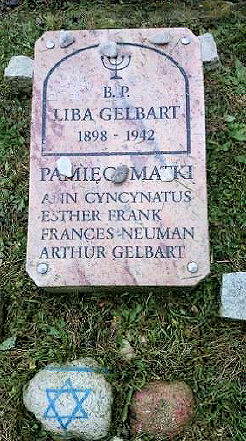

In the right-hand compound, there is another small tombstone erected by the family of a woman who, according to the testimonies, is probably was buried there. The inscription, in Polish, reads:

On blessed memory

LIBA GELBART

1898-1942

IN MEMORY OF MUM

Anne Cyncynatus

Esther Frank

Frances Neuman

Arthur Gelbart

The entrance to the left compound is alongside a building.

On the paving stones, leading to the mass grave, is an inscription created by students of the Częstochowa Fine Arts High School.

A satellite image of ul. Kawia.