Machel Birencwajg

- craftsman, head of the Möbellager and a leader of the Jewish underground

Machel Michał Birencwajg was born on 10th July 1907 in Częstochowa, the son of Icek Majer and Bajla née Kurnendz. He was a craftsman, communist and leader of the Jewish underground.

Machel Michał Birencwajg was born on 10th July 1907 in Częstochowa, the son of Icek Majer and Bajla née Kurnendz. He was a craftsman, communist and leader of the Jewish underground.

He received a traditional Jewish education in a cheder, after which he studied at the Jewish Gimnazjum. There, he joined the Zionist circle and was also a member of the Ha’Shomer Ha’Tzair scouting movement, as did his elder brother Pinchas and sister Mania (Ruchla). Machel was a charismatic, daring young man, full of energy and an accomplished skier. Very soon, he came to doubt the Zionist ideal and joined the illegal Communist Party

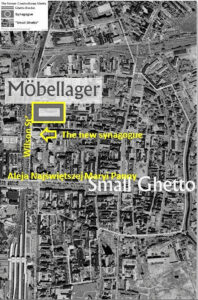

One of the most important forced labor camps in Częstochowa, during the German occupation of WW II, was the Möbellager (furniture warehouse) (ML) located at ul. Wilsona 20-22. It was on the outer edge of the ghetto, while the other side faced the “Aryan” part of the city. The grounds, spreading over two large yards, with storage facilities, belonged to Lewkowicz before the war, and Wajsberg also had his factory there. The Möbellager grounds were under the jurisdiction of the City of Częstochowa and Mayor Linderman assigned its supervision to Paul Lange.

Lange was a soft-spoken man and, amongst the few children in the Möbellager, they referred to him, “Those wearing a brown uniform they are nice guys, but those in a black uniform, oh boy, they are mean. He was nicknamed “Chazn”.

After the mass deportations to Treblinka, starting 22nd September 1942, almost all children his age had disappeared from the streets of Częstochowa. For this age group, the city had become  essentially “Judenrein”.

essentially “Judenrein”.

There was a rumor in the Möbellager that Lange, certainly, knew all the time about the “bunkers”, where mothers with their children were hiding, but probably for his own security he withheld his secret.

Lange would spend his days bored in his office. When he learned about Machel Birencwaig’s popularity among his fellow workers, he entrusted him with the management of the Möbellager. In essence, Machel became the Möbellager’s CEO much to the relief of Lange who, from time to time, could leave the city on a bird hunting spree.

Machel’s popularity reached outside the bounds of the Möbellager – people in the ghetto nicknamed the Möbellager the “Machel Lager”.

Lange’s decision, to hand over full powers to Machel, was a gift of Providence, as it gave Machel and his colleagues the opportunity to save many lives from the hands of the murderers. During the deportation of the Jewish population from the ghetto (in September and October 1942), Birencwajg and his companions saved hundreds of Jews and hid them in the Möbellager.

Following the opening of the “Small Ghetto”, they were smuggled there, despite the presence of Germans and two Jewish spies (“Kulibajki” and Gnata), who were specifically sent by the Gestapo. These activities were made possible due to Birencwajg’s determination and mental resilience. (Mothers, with their children, were transported inside wardrobes, sofas, and chests, and were hidden in shelters prepared by the underground.)

Workshops were built in the Möbellager, which employed professional Jewish tradesmen in many areas of competence – carpenters, locksmiths, electricians, sanitary specialists, automobile mechanics, painters, upholsterers, curtain decorators, etc.

When Machel took over, sixty craftsmen worked there but, following the 22nd September to 4th October 1942 deportations, when 40,000 people were sent to the Treblinka death camp, he negotiated with Mayor Linderman for more help, and their numbers soon doubled. They then called in the rest of their families from the ghetto, and the number grew to around 400.

After the deportations, teams of workers were sent out from the Möbellager to the ghetto, which had turned into a ghost town, to collect furniture and valuables from the now empty homes. This mission was assigned to Machel Birencwajg.

Carl Langner writes:

“One day, Machel learned that there was still a family hiding at Aleja 10. He sent a group, comprising his brother Pinchas and his cousin Jankev (Mojs) Rajch, to get them. They took a horse-driven platform charged with furniture and machines, found the family and smuggled them. The children were hidden in sacks surrounded with machines. On the way back to the Möbellager, they had to pass through German and Ukrainian control stations. One of them was corrupt, but another was not. They all risked immediate death if anything was uncovered.“

However, perhaps the most spectacular rescue occurred on that fateful Yom Kippur on 22nd September 1942, when the first “Akcja” took place, and a few thousand of the “selected” were sent to the Treblinka death camp. The route to the Umschlagplatz, the train station near the Warta River, led along ul Wilsona. As the crowd was passing the Möbellager, Machel and a group of workers, in a daring and heroic move, taking advantage of the turmoil, somehow distracted the Schutzpolitzei guards away from the gate. When the terrorised and panicked crowd of elderly people and mothers with their children came near, many rushed inside the open gate. Up to six hundred people were saved that day.

When the “Small Ghetto” was opened in November 1942, Hauptman Paul Dagenhardt ordered the Möbellager workers to move to there and live at ul Nadrzeczna 88. Immediately, Machel had them build there four new “bunkers”. This was important, as it allowed the transfer of the elderly and the children, when the “bunkers” in the Möbellager became too crowded. At the beginning of November, a large number of children were sent there.

One such smuggling is described by Leber Brener:

“Children were hidden in coal crates, furniture or wrapped in old clothes. The horse-driven cart was also loaded with a large pile of old clothes. At the entrance to the gate, Machel ordered the bundles of clothes to be unloaded and, while the guards were busy checking their content, Machel whipped the horse and the cart, with the children, rushed inside. This maneuver required steel nerves, and Machel was the man.

A detailed account of the activities in the Möbellager, and the role of Machel Birencwajg, is also provided in the testimony of Leon Silberstein:

“At that time, there was already a Möbellager for the plundered Jewish furniture. It was headed by Machel Birencwajg, who played an important role. My group also worked there.

“When furniture was brought inside the Möbellager, some Jews were also smuggled inside, especially children and elderly people, that is, those who were not able to work and risked being shot dead. Such people were brought in inside cupboards and we drove them inside the Möbellager. That is how we successfully saved a large number of children and elderly people, who for sure, would have been selected during an ‘Akcje’.”

At all times, Machel was in contact with the underground in the ghetto and was a key man of ŻOB (Jewish underground movement).

Clandestine activities, crucial for the underground, were carried out in the Möbellager. False identity cards (Kenkarte) were printed allowing people to escape to the “Aryan side”. Hand grenade parts were made there and, later, assembled in the “Small Ghetto” under the guidance of Heniek Wiernik. Some of these grenades had been smuggled out and sent to the Warsaw Ghetto, where they were used against the Germans during the 19th April 1943 uprising.

Living conditions in the Möbellager were not as drastic as in other forced labor camps, such as in the HASAG camps outside of the city. Nevertheless, food was rationed and every workshop worker received his meager daily portion. This posed a problem for the families hiding in the “bunkers”, since they were clandestine residents. It became even more critical after the 22nd September 1942 deportations, when a large number of people unexpectedly flocked into the Möbellager and Machel had to build new “bunkers” for them. Thus, after a hard day’s work, and waiting for darkness to fall, Machel and his elder brother Pinchas went from “bunker” to “bunker” and gave away a part of their food portion to those hiding, brought them fresh water and carried away their waste.

On the 8th June 1943, Hauptmann Paul Degenhardt, with his Schutzpolitzei, having been tipped by a Jewish informer, burst inside the Möbellager aiming to liquidate it. He shouted out an order to get Machel and his family. Machel quickly realised that he was in danger, and ran to the second yard to hide. “They’ll never get me alive”, he said to colleagues as he fled.

During their search, they found his 72-year-old mother Bajla, hiding in a public toilet in the second yard. They beat her cruelly, so she would reveal Machel’s whereabouts. People in the first yard heard her screaming “Bitte nicht schiessen, nicht schiessen”, as she desperately pleaded for her life – Degenhardt killed her.

They then found Machel’s wife, Hadassah (Hania) nee Feldman. They took her to the Zawodzie prison from where she was later taken to the Jewish cemetery and was murdered there together with friends.

Pinchas, with others, was standing in a row, while the search continued. He was eating his new Kenkarte with the Aryan name “Piotr Stanislawski” and trying to swallow it. If ever they had found that ID card, they would shoot him dead on the spot. A Schutzpolitzei officer came near and asked him about Machel, and punching him in the face and breaking his teeth. He then pulled out his gun, pointed it diretly at him, but he did not pull the trigger, saying, with a waive of his hand, “Ach, du kommst so wie so Um”, (You will perish anyway.). He put the pistol back into his holster. Pinchas was taken to the Gestapo. At night, he jumped out of the first floor window onto the top of a tree below and ran to hide in the “Small Ghetto”.

Colleagues decided that Machel would now be safest outside of the Möbellager. So they resorted to a well-tested technique – they smuggled him out inside an empty cupboard in a horse-driven cart. As they approached the gate, Machel shouted to friends below, “Ratujcie się, ratujcie się !” (“Save yourselves! Save Yourselves!”). He somehow felt that he would never see them again.

He went into hiding on the “Aryan side” of the city, in the apartment of a Pole whom he knew and trusted. This young man, ever since he was a teenager, worked for many years at the Birencwajg’s store and workshop on Aleja 10. He earned a decent living and was able to provide for his family. Soon after, however, he blackmailed Machel by asking him for money. At one point, Machel summoned Leon Zylbersztajn to bring him some jewellery to satisfy the Pole’s demands.

Even in such a desperate situation, the odds had been in Machel’s favour. He had a Kenkarte with a fake Polish name, allowing him to travel outside of the ghetto. He did not look Jewish, and he spoke and wrote Polish like a a non-Jew. Moreover, he underwent surgery so as to mask his circumcision. He could have easily survived the war, just like his cousin Jankev (Mojs) Rajch and Berek Wajsberg, who both fled to Switzerland and survived . But he stubbornly refused, saying that he would not abandon his beloved. So, he waited, hoping to get a chance to deliver Hadassah from the hands of the Gestapo.

On the 19th of June, a dramatic graffiti from ŻOB appeared on a wall in the ghetto. The scribbled words said, “MACHLA NIEMA , MÖBELLAGER DD, ODCIĘCI DN 19.VI.43”, meaning, “Machel cannot be found, the Möbellager is finished. We are cut off”, followed by the date above. Sometime later (date unknown), two Schutzwerk Politzei broke into the apartment of the Pole. They pulled Machel foutrom under a bed and took him to the Gestapo.

Machel was tortured. As a member of ŻOB, he took orders directly from Mojtek Zylberberg, and knew the names and the hideouts of colleagues, and the caches of weapons and money. Inmates saw him being brought back into his cell unconscious. On the 29th of July, Machel and several inmates, were loaded onto a truck, driven to the Częstochowa Jewish Cemetery and ordered to undress, as was the rule. A supreme humiliation. Machel refused and was cruelly beaten before he was shot dead.

Webmaster’s Comment:

The text on this page was prepared by

Mark Stanislawski-Birencwajg

– Machel Birencwajg’s nephew

and

Wiesław Paszkowski

– historian of the

Częstochowa Historical

Documentation Centre

Mark Birencwajg’s Story

At the time of the liquidation of the ghetto in September 1942, Mark was five-years-old and, together with a group of children, hid in the Möbellager.

One day, in the winter of 1942, he was with his grandmother Bajla, sitting next to the warm stove, when a man suddenly opened the kitchen door from the outside yard. His grandmother instinctively threw herself against him in order to protect him with her body. It was Lange, the Möbellager supervisor. He stood at the entrance showing his sore finger. Bajla went over and treated him with iodine and a band aid.

When the situation became dangerous, with the intention of saving him, Mark’s parents gave him to a Polish family.