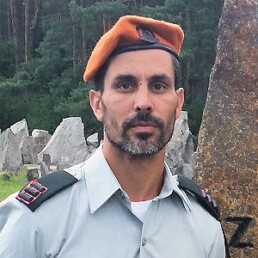

Tomer Gekler

My Częstochowa

by TOMER GEKLER (Israel)

When did my roots journey begin?

Maybe it was after I returned from “Witnesses in Uniform”, a journey of a group of IDF soldiers to Poland as part of my reserve service?

Maybe, when I suggested to my mother that, in honour of her 70th birthday, she should come with me on a family roots tour of Poland and Lithuania?

Maybe, right when we boarded the plane to Poland, after four hours of waiting in the Ben-Gurion Airport?

The truth is that, for me, the journey started right from the day I was born.

BACKGROUND

I am Third Generation of Holocaust survivors, who tried with all their might to live a normal life – tried and did not always succeed.

Apparently we lived an ordinary life. The stories of the Holocaust, which we heard at home from time to time, seemed to us to be heroic stories about heroes, who fled and survived, kinds of supermen who lived with us. We didn’t really understand the stories of the horrors that, from time to time, were shared with us. Our young souls were too delicate to understand, but the story was implanted within us. Even more than that, we also absorbed the anxiety, the survival instinct, the determination, the perseverance and the lust for life.

And there was also a considerable amount of constant sadness, which accompanies us as a trans-generational inheritance without our always knowing its origin.

My journey to Poland and Lithuania begins with a search for the roots of all my grandparents, who survived there by the skin of their teeth. I arrive in Częstochowa following one of them – Aryeh Leib Kolin ha’Kohen (“ha’Kohen” referring to the priestly class of which he was a member) or as he is known to me, “Grandpa Aryeh”.

Grandpa Arya died when I was nine-years-old and my childhood memories of him are very sketchy. As a child, I experienced my grandfather as an elderly man, whose character was the product of his Diaspora upbringing. I never really engaged with him. When I was nine-years-old and my brother, Yoav, had his bar-mizvah, Grandpa Aryeh gave me a small tallit as a gift, a tallit which, over the years , was left in my mother’s cupboard, patiently waiting for me to go and seek the grandfather whom I never really knew.

I began my renewed journey, to get to know my grandfather at an older age, after years of running away from the stories of the Holocaust and my family history. Like everyone else, I wanted to be the most Israeli, the most cosmopolitan, the most educated, the coolest, the most ….. But there is a moment when a person stops and looks at his life and questions who he really is. For me this moment began to sprout towards the age of forty. My two young children had grown up in a global and western culture, and I began to ask myself, what did I want for them and what did I want for myself.

Right at that time, on a summer day, the phone rang. It was the liaison officer of the reserve battalion in which I served at the time. I was expecting the standard summons to report for reserve duty but, instead, the liaison officer had a surprise – “we have been assigned to take you on a ‘Witnesses in Uniform’ trip to Poland. The truth is that I was surprised and, although I didn’t officially refuse, I decided that this was not for me and that I would not join this trip. For me, my involvement with the Holocaust narrative ended with my high school memorial ceremonies.

It took me another week of reflection, and talking with my older brother, for me to realise that I had nothing to lose. If someone offers you a trip abroad for free, you don’t say no, even if it’s to Treblinka. These were,s more or less, the considerations I had at the time for either going or refusing.

Six years before that phone call, my father David Gekler had died of cancer. In the months after he passed away, I found myself having a hard time recalling the beautiful moments, life before the illness and the moments of grace in the last months that I had accompanied him. All I could remember were the difficult moments in his last days and hours. This difficulty sharpened my understanding that traumas, whether they are personal, communal or national, have the ability to take over memory and, ultimately, one’s being. This insight suddenly dawned on me during the long trips during the “Witnesses in Uniform” trip to Poland.

There was this realisation that our observations of Jewish life before the Holocaust were, intentionally or unintentionally, coloured by the gloomy colours of their final chord – the Holocaust of the Jews of Europe and the personal Holocaust of my family.

With this understanding, I set out to collect fragments of evidence and stories that would help to understand the sequence of generations, rich in conceptual and cultural depth, that will connect me to my roots and to the source from which I came.

PLANNING THE TRIP

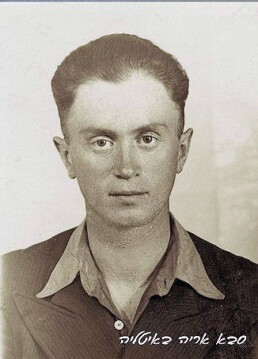

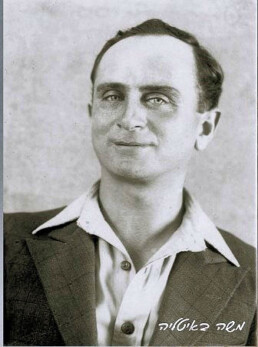

Aryeh Leib Kolin was born in Częstochowa on 8th April 1913, to a traditional religious family. That having been said, from the few stories which I was able to collect, it seems that, besides great loyalty to the tradition of our ancestors, the family was open to modernity. My grandfather Aryeh Leib and his brother Moshe belonged to the ultra-Orthodox sect of Radomsker Hasidism, which was very active in the Częstochowa area before the Holocaust. Apart from this fact, I was not able to find out much about life before the Holocaust. Grandpa Aryeh had two sisters, Sarah and Rachel, who were probably sent to their deaths in Treblinka, just like like their parents Frida (nee Rajch) and Szalom Kolin.

After my having spent two years of work in New York as an emissary of the Jewish Agency, I began planning our family trip to Poland in honour of the 70th birthday of my mother, Shoshana Gekler, Aryeh’ daughter. Haim Gekler, my uncle, also the son of Holocaust survivors, and his wife Evelyn, also joined the journey. Together, we left with many pieces of information and with mixed emotions, trying to understand the incomprehensible.

I learned about my grandfather’s bravery and the depth of his personality in preparation for the family trip. Grandpa went through the Holocaust, together with his brother Moshe Kolin, in the Częstochowa ghetto and in the Częstochowa forced labour camp, HASAG-Pelcery, which was a factory that made ammunition for the German war effort.

THE TRIP

When we set off from Kraków to Częstochowa, I did not know that the buildings where the factories were located were, in fact ,still standing. The visit to the factories was actually the first time that we had personally encountered “a station” on the journey which connects to the personal story of my family. I was astonished at the thought of the long days and hours, which my grandfather wold have worked here. Mostly, I was occupied by the thought of his thoughts at that time. Was he thinking of me? About a grandson who will, one day, be able to live in the State of Israel? What kind of hope kept him going during those long hours which he worked in the forced labor factory?

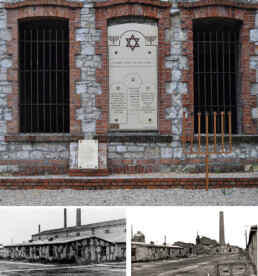

Not much remains of the factory itself, an old and ruined brick building. But, thanks to a commemorative plaque placed on the spot by the World Society of Częstochowa Jews and their Descendants, we could feel the intensity of the place.

After visiting the city, we visited the Jewish Museum of Częstochowa and the hiding bunker at Stary Rynek 24 (Old Market Square), where the Frajman family hid. Only there, when we went down to the bunker, could we feel the pain of those who had hidden there. We also visited the memorial monument to the Jews of Częstochowa, located at the Umschlagplatz, from where about 40,000 Jews were deported from the ghetto to the death camp in Treblinka – including, apparently, members of my family.

We walked the streets of Częstochowa and the streets where the ghetto had been. We looked at the houses, the stones and the people and my thoughts and imagination wandered to the time when my grandfather and his brother Moshe walked these very streets.

TRIP HIGHLIGHT

The highlight of the visit to Częstochowa was actually at a site which is not directly related to the memory of the Holocaust. Before we left Częstochowa, and with the kind help of Alon Goldman, chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel, we were able to locate the residential address, where my grandfather lived with his family.

We did not know if the original residential building still existed and, when we arrived, we were in for a surprise. The apartment building at ul. Garncarska 11 not only exists, but it has been preserved almost in its original version and design. It is a two-storey, burnt-red brick building,with an inner courtyard surrounded by a large abandoned building. We entered the building’s courtyard and the stairwell. For a moment I could imagine my grandfather, as a young man, descending those stairs in front of us.

(Below: my mother and me in front of that building)

SOME FAMILY HISTORY

The visit to Częstochowa was short, but it was a significant starting point for the rest of our journey in Poland and Lithuania. And as for my grandfather, “Grandpa Aryeh”, he survived the Holocaust, together with his brother Moshe and was among those Częstochowa children who were freed, on 17th January 1945, when the Russians liberated Częstochowa.

Like many other Survivors, they began their journey towards the Land of Israel and found themselves in a refugee camp in Italy waiting to immigrate to Israel. That is where my grandfather Aryeh met my grandmother Sara, also a Holocaust survivor, and that is where they decided to marry. Soon they had a son Yosef, my mother’s older brother. Unfortunately, Yosef was not a healthy child and their aliyah plans had to be put on hold. They moved from Italy to Finland, where my grandmother’s sister lived even before the War. My grandparents lived there until 1972 and, only then, when they were both approaching the age of sixty, did my grandparents realise their dream of immigrating to Israel. They did this following my mother, who had immigrated to Israel alone a few years earlier at the age of sixteen.

Despite the memories of the Holocaust and many other difficulties which befell my grandparents, they did not lose their vitality and lust for life. Grandfather became a resilient and successful man. He opened a prosperous business and continued to maintain a Jewish way of life, raising descendants who are, today, also parents and grandparents.

In moments of challenge and difficulty, I often find myself reflecting on my grandfather Aryeh, and not only on the story of his survival during the Holocaust. I rather focus on the life which he built for himself after the Holocaust, his insistence on living, starting a family, prospering in business and fulfilling his dream of immigrating to Israel – all of which are a source of inspiration for my daily life’s work.

We thank Alon Goldman, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel,

for helping me prepare for the trip and for encouraging me to write down my impressions.

Steve Forberg

My Częstochowa

by STEVE FORBERG (Toronto, Canada)

BACKGROUND

My grandfather, David Forberg, was born in 1922 in Częstochowa, Poland. He passed away in 2011.

Through the years, as a grandchild of two Holocaust Survivors, I heard many stories and real-life accounts from my grandparents, Syma and David. My grandparents met, during the war, in the HASAG-Pelcery forced labour camp in Częstochowa. Many of the stories, which I had heard, were about “the old country” and about life before the war with their families.

I had never been to Częstochowa nor has any member of my extended family been back since my grandfather was liberated in 1945. He never wanted to return and discouraged his children, also, from setting foot back in the country that changed his life forever.

They say, you can’t go back to a place which you never left. But, for me, I was going BACK as Częstochowa was where my roots began.

David Forberg had four Children – my father Joe , Honey (Silverberg) Esther (Michaels) and Bill Forberg. Together, they have ten grandchildren and twenty great-grandchildren to David Forberg.

I felt honored to be the first one to report back to my family on my experience.

OUR VISIT TO CZĘSTOCHOWA

I, Steven Forberg, at the age of forty-three, was traveling in Poland, together with my wife Sue and two sons, Josh 16 and Ryan 14 – with Sue’s family, whose father is from Poland. For his 75th birthday, for ten days, we all went to Warsaw, Kraków and Krynica. Since I would be so close, I decided that I would arrange a day, from Kraków, to make a side-trip, with my wife and kids, to the town about which I’d heard so much – where the Forbergs began -Częstochowa.

Through my Aunt Esther, I was connected to Alon Goldman, with whom I spoke with about my plans, prior to leaving Toronto, Canada. Alon put me in touch with Małgorzata and Marek Małecki, who live in Częstochowa and provide tours for people, who come back to visit the old town. I really didn’t know what to go see or what I wanted to see, other than the Jewish Cemetery and the address of where my grandfather had lived. I ended up seeing much much more.

I went with an open mind – more like a sponge as I wanted to soak it all in. I really wanted to see it from the perspective of how, I think, my grandfather’s life was before 1939 and how he lived.

Where did he live ? Where did he have his bar- mitzvah ? Where did his family go to synagogue ? What was the town like that where he would run around on the streets as a young boy during his brief time of innocence.

On 21st July 2017, at 10:40am, I was greeted by Malgorzata and Marek at the Częstochowa railway station . This wasn’t a day for good weather as it was pouring rain all day long.

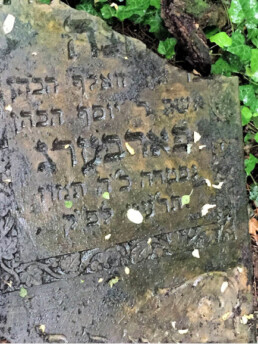

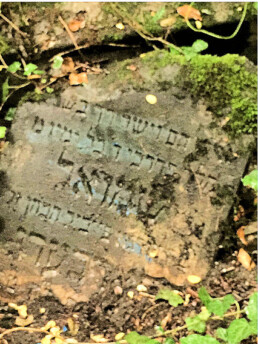

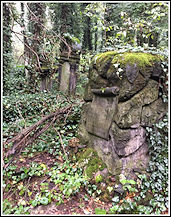

We got into the car and our first stop was the Jewish Cemetery. I had visions of a typical cemetery but, when we arrived there, I knew that this was far from any typical cemetery. The street that led us to the entrance of the cemetery was hidden and far removed from the main streets. The cemetery entrance was set back and it appeared to me that this cemetery doesn’t get many visitors.

We exited the car into the pouring rain, with three umbrellas for the six of us. We begin to walk into the cemetery, down a path which seemed rather new, but which led us to the unkempt grounds . Marek led us off the path into the woods, towards four gravestones of members of my family. Now, picture walking through a forest with overgrown weeds and ivy everywhere.

We had to step over all this on the way to the tombstones we were in search of. We began to get wet, very wet. The insects biting us were plentiful. We were also walking over many broken tombstones, fallen tombstones and soaking wet soil as we finally arrived at Samuel and Hana Forberg’s tombstones.

For a moment, I stood in amazement, not knowing who these people were in relation to me. At that moment, it hit me that my Forberg family roots were here and not just my grandfather’s.

I paid my respects, took some photos and said a prayer over both headstones, accompanied by my sons who, with me, had braved the trek through the woods. It was pouring rain and it was too difficult and emotional to continue on to see the other two Forberg tombs. The rain was coming down so hard, I thought to myself that my grandfather was definitely looking over me and shedding his own tears with us or that he had wished that we didn’t go back and was trying to hurry us along.

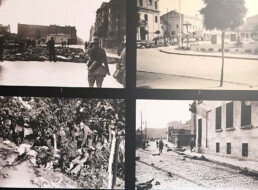

We were take to an open area, where we were shown the grave site, where several mass executions committed by the Germans. So many thoughts were running through my mind. But the one which stood out most was, “What horror would my grandfather be feeling, when his town was being invaded by the Nazis ?”

Wet and cold, we got back into the car and headed to the Częstochowa Jewish Museum, where we could get out of the rain and dry off. As we drove from the Cemetery to the Museum, I looked out the window during the entire car ride (as I did much of the day). I was trying to imagine life here between 1939 and1945.

We parked and walked a short distance to the new Częstochowa Jewish Museum, which recently opened in September 2016. There was no big signage or anything to indicate that there was a museum on this street. Just a small plaque outside the main doors.

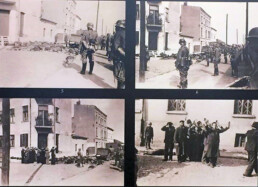

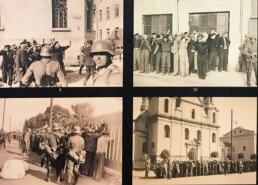

We entered and took a tour through the exhibition, which was very well done. It takes you through Jewish life in Częstochowa prior to 1939 and shows how vibrant it was when the town’s population was 130,000, of which 30% were Jews. From the Old Synagogue and New Synagogue, the Jewish district, the town’s Rabbi and so forth.

Then images of the Germans, in the town square, rounding up the Jews and herding them out. As you walk through the Museum, it brings you back in time to what life must have been like. How terrified my ancestors must have felt when the Nazis took over their city and all of Poland.

(Click on each of these three images to enlarge.)

In 1942, the Germans established a small munitions factory (HASAG-Pelcery) , which operated until liberation in January 1945.

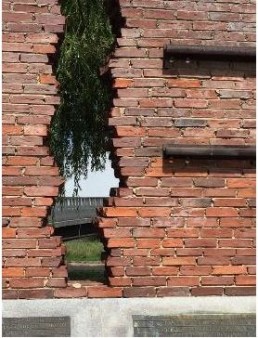

I was in utter amazement when I arrived there and stood in the rain looking at this building. During the tour, Marek explained the use of these dilapidated buildings and what transpired inside them. We were told how the workers were brutally treated, poorly fed and how they lived in the worst of condition. Many had to walk miles daily, from the Częstochowa “Small Ghetto” to this slave labour work camp, where they made ammunition to kill other Jews.

The building was untouched since 1945. In three different languages, with the Star of David, there is a memorial plaque on the outside wall. The brick was dark and broken, the windows non-existent and the main entrance to this HASAG had broken glass windows, which resembled an Alfred Hitchcock horror film.

One side of the building still had, on it, the original fencing and barbed wire. Across the street, from the walls of horror, there were homes and people living a normal life, which amazed me. I looked into the building and could only imagine the conditions of the workers, the lack of food and water and the Germans, standing in the spot I stood during their time of power, and how angry I felt standing there.

I thought to myself, “Were my grandfather’s brothers and sisters, mother and father, aunts and uncles in this building?”. My grandfather was in the Skarżyko-Kamienna HASAG.

In January 1945, 5,000 slave labourers were liberated in January 1945 – the largest of any liberation in Poland and only 1,500 were Jews were from Częstochowa.

(Click on either image to enlarge.)

From there, we ventured to the banks of the Warta River, next to which stands the Częstochowa Jewish Memorial. To my shock and dismay, this memorial was only erected in 2009. What took so long ? The memorial is a brick wall – wide, tall, yet simple. The brick wall is broken into three sections. The first has two smooth railway tracks hung parallel against the brick wall, symbolising the smooth and simple life the Jews had before the war. The second has a split with missing bricks, which that resembles a crack in the wall, depicting the break of normal life which was the horror of the Holocaust. The last section is the Star of David made of old railway tracks and shows that Jewish life had survived the war and again is thriving today.

It was an eerie feeling to be standing in the same spot from where the trains had left to the death camp of Treblinka. Just a few yards away, stood a barricaded old railway house through which each Jew must have gone through prior to boarding the cattle cars to their deaths. How this building is still standing was a surprise to me but, if it’s a reminder of the hell that went on here, then it’s there for the world to see.

There’s a gravel path, where the old railway tracks once lay and from where the trains departed. In awe, I stood there, staring down this path, knowing that 40,000 Jews had left from this very spot – from Częstochowa to Treblinka.

The site also has an original German train manifest, enclosed in a glass, displaying the schedule for the deployment of the trains. A schedule of various locations, dated 1942, and this particular one, shows Częstochowa on the list with the final stop in Treblinka.

To visualise this made this Memorial even more chilling. The shock wasn’t just on my face, but on the faces of my two sons and my wife as I explained what had really transpired, in this very spot, just decades ago. My kids were well aware of stories of the Holocaust but, at that moment, they felt the reality of it all. It was very emotional for me knowing my grandfather was the only survivor and that his first wife and new-born child were on one of those trains to Treblinka and were murdered.

(Click on either image to enlarge.)

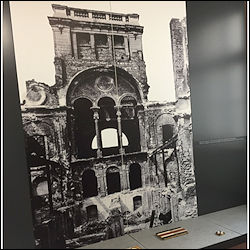

From there we toured the “Big Ghetto”and “Small Ghetto” areas. We walked and saw where the Old Synagogue once stood, which is now an abandoned lot. This first synagogue in Częstochowa was set ablaze by the Nazis. There was only one five-foot wall of the old stone synagogue still standing from before the war.

From there we toured the “Big Ghetto”and “Small Ghetto” areas. We walked and saw where the Old Synagogue once stood, which is now an abandoned lot. This first synagogue in Częstochowa was set ablaze by the Nazis. There was only one five-foot wall of the old stone synagogue still standing from before the war.

We walked to the Old Market Square (Stary Rynek), the small shops that aligned the main streets and to the address where my grandfather had once lived – ul. Warszawska 30/32 (pic left). Today, the address is a newly-renovated three-storey large building.

Many surrounding buildings were old. I stood there and stared at the building at the address I was given and looked around. I was in awe thinking that I was able to stand in the exact spot that my Zadie (grandfather) lived. I thought about all the terror, but the strength he had to have to survive. It was a miracle that he survived it all, but as my Zadie used to say, “It was all luck”.

We then saw the huge church where my grandfather was held during the first days of the Nazi occupation of Częstochowa. This was where he stayed for days, with no food or water, in unsanitary conditions. This is how the Nazis weakened and demoralised hundreds of Jews, so they couldn’t fight back. Again, I was imagining him, as a young man 17/18 years old, as his life was being turned upside down.

POSTSCRIPT

My time in Częstochowa gave life to the stories that I’d heard about before the war, but also to the horrific stories that my grandfather had told me about the Holocaust.

It was different in the sense that I could finally visualise a little of what took place. How much I wish he was still here with us so that I could tell him I was there, tell him what I thought, but more importantly, to ask what would he have thought.

I do understand though why he never wanted to return, as it would have opened so many old wounds that I am sure he would never have wanted to relive.

Was he a survivor ? Absolutely!! He was also the toughest man I ever met and, for him, to restart his life after the war, after all he went through, is a true result of his strength.

I miss my grandfather and think of him often

but, on that day, I know he was with me every step of the way.

Submitted by:

STEVE FORBERG

Elena Feder

For My children, Ari and Sharon, and For Theirs ...

by Elena Feder (Vancouver, Canada)

I travelled to Częstochowa in September 2016. It was the first time I set foot in the country where my parents were born; the land they fled with no desire ever to return; the world that took from them loved ones, their youth, dreams and aspirations, and irremediably destroyed their lives.

So strong was their rupture with the past, that they chose not to teach their children Polish, the language in which, in their eyes, unspeakable atrocities had been carried out. For them, the Polish neighbours with whom they shared a life had all but aided and abetted the murderous actions of their German masters. At home in Bolivia, I spoke Aymara and Qechua with my nannies, Spanish later at school. With my parents, it was always Yiddish, the mameloshen.

Thus it is no surprise that Poland was never high on my list of places-I-must-visit. Had someone asked me why I was going, I might have reasoned that Częstochowa was where my mother and her four brothers were born, that I knew nothing about their lives, and even less about the grandparents, great-grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins I may have had. My mother was not the garrulous type.

In truth, I hadn’t formulated any questions, let alone found answers to guide me out of the maze I unknowingly had set out to unravel.

I went as one of the 130 participants in the Fifth Reunion of The World Society of Częstochowa Jews And Their Descendants. The First Reunion took place in 2004, but I only learned of the Society’s existence a few months before going. The hook was a link on their website to The Return of the Violin, a stunning documentary that tells the story of how a 1713 Stradivarius, stolen from the internationally renowned violinist Bronisław Huberman at Carnegie Hall in 1936, returned sixty five years later to his native Częstochowa in the hands of its new owner, the legendary Joshua Bell1.

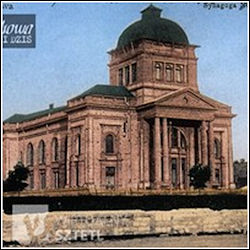

I was mesmerised by the story. I had heard that my grandparents owned a paint/hardware store not far from the destroyed New Synagogue where the concert hall now stands. Dots kept connecting. I decided to go.

The New Synagogue and (left) an architectural wonder burned to the ground by the Nazis in 1939.

The moment I set foot on the minibus connecting Warsaw to Częstochowa, I was transported onto the set of an unfinished movie running unheeded in the deepest recesses of my brain since forever.

The language was incomprehensible and my knowledge of the social, cultural and political histories of the land of my ancestors rather superficial. Yet it all seemed strangely familiar, uncanningly like home; even the language. The ten passengers on the bus (French, American, Australian and Canadian) felt like extended family. So did most of the people I would later encounter.

Unsettled, I looked out the window for clues to my inner landscape. Everything I saw had meaning only in context. The present was impregnated by the past. The endless birch and alder forests at the sides of the road conjured images of emaciated ghosts, running for their lives tattered and terrified, begging for mercy, pitilessly gunned down by uniformed Nazis before the sometimes cowered but mostly gleeful eyes of their old compatriots. I could hear their muttered cries, the words of the Shema fade softly with their dying breath.

I shared my thoughts with the others. To my surprise, they too had had such visions. We share the nightmare. We also share the desire to find ways of coming to terms with it. Each in our own way, we were piecing together the frayed remnants of a common past, hopelessly unaware where the road would take us. We later crossed paths at the Archives, shared our discoveries, supported one another when things got tough, celebrated everyone’s successes as our own.

The only Polish speaker in the group, a seasoned Australian on his fifth reunion (Webmaster: I suspect that was me.), asked the driver, on my behalf, if this modern highway had been built atop the old road between Warsaw, Częstochowa, and neighbouring towns like Radom, Kielce, and Pilica, my father’s hometown. No one knew.

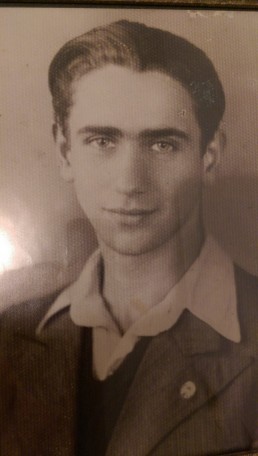

My father left for Warsaw to study dentistry, his life dream, in the mid-30’s. Armed with determination and a good dose of chutzpah, he handed his parents his newly-minted rabbinical title (Smicha) – obtained to soothe their fears that he might become a goy – cut his payes, and departed with a younger brother for the big city. By the time the War broke into their lives, the modernised yeshiva bucher had become a dental surgeon, read Mein Kampf in German, joined Betar and enlisted as a medic in the Polish Army “Where else could I learn to use a weapon?”2. A photograph of my father in uniform, his infantry cap irreverently misplaced, his gloomy brother and proud fiancée standing behind, leaning on his shoulder, speaks volumes. Neither survived. He was barely twenty three.

My father never forgave his Polish comrades for handing the Jews over to their captors. “Even the Nazi officer shamed and scolded them!” A breach of military etiquette, I guessed. In my eyes, no one could ever surpass the cold-blooded, measured, industrious barbarity of the Nazis; not even their eager collaborators. Besides, Jews fared no better when their own lives were on the line. “It’s not the same.” End of conversation.

Back there, where stories and places were coming together, I looked for markers of my father’s occasional trips home to see family, footprints of memories somehow transferred to mine. Other than the occasional centuries-old house in a village or an odd crumbling farmhouse far afield, I found none. Bare landscapes mimicked the erasure of the past. The murder of six million Jews, nearly half of them Polish with roots a thousand years deep, had left behind a haunting void.

Częstochowa, an important centre of Jewish activity before the War, offered a slightly different story. The town attracted large numbers of Jews from neighbouring provinces since the late 1700’s and, despite the typical animosities and the occasional Pogrom, the community prospered in this deeply Catholic town. By the 1930’s, a disproportionate number of the elegant two- and three-storey late-19th century houses and businesses lining the treed boulevard that leads to the world-renowned Jasna Góra Monastery, were owned by the wealthier. Jews were so central to the economic, industrial and social life of the city that even the icons and prints – sold by the millions to Christian pilgrims who traveled great distances to see the miraculous Black Madonna – were produced by them.

It is said that Jews had also fared better than anywhere else in Poland during the war. Not so.

When the German Army arrived in September 1939, Jews comprised approximately one-third of a total population of 135,000. By the end of the War, of the nearly 45,000 Jewish residents – of which only 28,456 were accounted for by the Germans before relocation to the Big Ghetto, in the poorer Jewish area of town – fewer than 5,000 survived. Of the 5,194 Jews who walked out alive from HASAG the morning of January 17th 1945, only 1,518 had been Częstochowa residents before the War, a mere 1,240 native-born – my mother was one. Approximately 3,000 more survived other camp, like my unle Yacob, or as partisans. Not exactly a stellar record.

One reason given for the purportedly high survival rate was Częstochowa’s strategic importance to the Nazi war machine. Four of the six armament factories in HASAG’s defense conglomerate were built there.3 As recorded in the original German Government workers lists (where I found my mother and one uncle), during the five years the camps were in operation, the number of labourers grew from 4,734 to 10,990.4 Only 2,490 were Częstochowianin, the other 7,500 were “selected” following transfers from nearby villages and camps. In 1942 alone, more than 20,000 people were forcibly transferred from neighbouring towns, raising the Jewish population to over 50,000, which turned Częstochowa into the third largest ghetto in conquered Poland after Warsaw and Łódż.

The HASAG-Pelcery Slave Labour Camp

I will never know if my paternal grandparents and their five murdered children were among those transferred in 1942 to Częstochowa from Pilica – a shtetl with a population of 1,711 Jews and a history dating back to the late 1500’s. It would have been the closest they would have come to crossing paths with their future in-laws, fantasmagorically prefiguring the tortuous road that led to their survivor children’s marriage.

I will never know, because the Nazis did not bother to keep records of their names or the names of the hundreds of thousands gassed, shot and buried in Treblinka.5 From Częstochowa alone, 48,000 Jews were packed into trains and “processed” in this forgotten hell on earth between September 22nd and October 7th 1942. A bare two weeks. Daunting.

The train station exterior, as it looks today.

I lit a candle and said Kaddish when we subsequently gathered at the Umschlagplatz Memorial, a striking monument unveiled in 2009, a few feet from the ramshackle remnants of the fateful station. Created by the late sculptor Samuel Willenberg, a Częstochowianin who miraculously survived the July 1943 Treblinka uprising, the memorial’s simplicity belies the profoundity of its message. Rusted train tracks, removed from the nearby station, are fastened to a severed brick-and-mortar wall, on one side in the shape of a star of David, on the other, in two parallel lines. A weeping willow mourns quietly behind the crack. A copy of a daily train schedule protected by two tall pieces of thick glass stands to one side like a silent witness.

The 2016 Reunion Memorial Ceremony at the Umschlagplatz Monument.

It was created in 2009 by sculptor Samuel Willenberg z”l, a native of Częstochowa

and the last survivor of the Treblinka uprising.

Four survivors, present at the Reunion, were honoured on this occasion.

From left: Gavriel Horwitz, Marila Rotfeld, Ada Ofir Frajman, and philanthropist Sigmund Rolat

Glass sculpture containing the train schedule6, with the train station in the background.

As if on cue, a sudden burst of heavy rain briefly interrupted briefly the rabbi’s heartfelt rendition of El Malei Rachamim.7 The heavens, too, were crying. “Too little, too late”, I thought.

There were other events – a banquet dinner, a guided tour of Jewish landmarks, two magnificent concerts, the unveiling of an abstract rendition of a chamber quintet by Israeli sculptor Anna Huberman-Lazowski,8 and an evening at the Jan Długosz Academy,9 where high school students unveiled projects referencing the past and present of their city in relation to the War – moving attempts of come to terms with a history their young minds can scarcely comprehend.

Most memorable was our visit to the HASAG Pelcery slave labour camp, a massive brick and mortar compound bordering the city, dedicated largely to the production of bullets and military uniforms during the War (one of my mother’s tasks). Across the road leading to the camp, stood two or three 4-storey buildings where doctors and engineers lived in cramped quarters alongside seamstresses, tailors, shoemakers and other professionals selected to serve the whims and needs of their Nazi masters.

Left: HASAG-Pelcery interior viewed from the street.

Right: HASAG-Pelcery memorial – with business signs on either side.

Thousands laboured and perished behind its walls. It was disturbing to see new industries in operation, their signs afixed to window bars that open to empty rooms, decaying walls and dusty dirt floors, their loaded trucks cutting into this hallowed ground incessantly.

One of the survivors, the indomitable Sigmund Rolat (left), founder and supporter of the World Society, bore witness to the horrors. Shaken yet contained, he spoke of life as child in that vile site, punctuating the personal with vivid descriptions of the camp’s day-to-day operations. Here, he pointed cane in hand, the metal was pressed; there, bullets were molded, over there washed… crated… loaded… shipped. In that courtyard, he gently bemoaned, people were regularly shot, punitively or at whim

we watched from the kitchen. Each prisoner, he sighed, worked two daily shifts of ten hours on starving rations.

One of the survivors, the indomitable Sigmund Rolat (left), founder and supporter of the World Society, bore witness to the horrors. Shaken yet contained, he spoke of life as child in that vile site, punctuating the personal with vivid descriptions of the camp’s day-to-day operations. Here, he pointed cane in hand, the metal was pressed; there, bullets were molded, over there washed… crated… loaded… shipped. In that courtyard, he gently bemoaned, people were regularly shot, punitively or at whim

we watched from the kitchen. Each prisoner, he sighed, worked two daily shifts of ten hours on starving rations.

The accumulation of details fleshed out the horror and gave the unimaginable the weight of the real.

Rolat’s story is exceptional. Born Zygmunt Rozenblat to a wealthy Częstochowa family, he lost both parents, a brother, and his devoted Polish nanny in the War. When he was fifteen, he made his way to the New World by dint of wit, eventually becoming a successful entrepreneur with businesses in the U.S. as well as Poland after the fall of Communism. An art collector, music aficionado and philanthropist, with a mission to preserve Poland’s rich Jewish history, Rolat is a founding member of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, the main contributor to the annual Jewish Culture Festival in Kraków, and an ongoing supporter of the Częstochowa Huberman Philharmonic. Along with Alan Silberstein and Alon Goldman, Simund Rolat was the driving force behind the creation of the Częstochowa Museum of Jewish History, inaugurated with great pomp and circumstance during our visit.10

The Mayor of Częstochowa placed countless resources at our group’s disposal and spoke at practically every event, with particular eloquence at the highly publicised visit to the Jewish Cemetery. Established between 1799 and 1804, the cemetery is a testament to the long-term commitment of the community to its city. Though its 8.5 hectares now cradle fewer than 2,000 surviving gravestones, jostled by crawling roots, bedecked by moss, hopelessly cramped by tangled brushes and sky-defying trees, several newer monuments have been erected to honour War victims.

The Mayor of Częstochowa placed countless resources at our group’s disposal and spoke at practically every event, with particular eloquence at the highly publicised visit to the Jewish Cemetery. Established between 1799 and 1804, the cemetery is a testament to the long-term commitment of the community to its city. Though its 8.5 hectares now cradle fewer than 2,000 surviving gravestones, jostled by crawling roots, bedecked by moss, hopelessly cramped by tangled brushes and sky-defying trees, several newer monuments have been erected to honour War victims.

Germans and their collaborators wrecked havoc at the cemetery from their arrival in 1939 until 1943, a year mired by mass executions. On March 19th, six resistance fighters were executed against a wall11; the next day, German soldiers shot 127 no-longer-needed professionals and their families: doctors, lawyers, engineers, and members of the Jewish Council; the 26th of June, they destroyed the remaining Small Ghetto, murdering some 1,500 people; on the 20th of July, hundreds of slave labourers were executed. Children were killed en masse at different times. When the War ended, hundreds of mass graves were exhumed by survivors and given a proper burial.

One of the mass grave memorials. The plaque reads:

“In this very place, on July 21st 1943, Germans and Ukranians shot over 200 Częstochowa Jews.

With the passing of time, only these individuals are still remembered (names follow)”.

Frustrated by the rain and by the fruitless search for family gravestones, my cousin and I left for the City Archives (Archiwum Panstwowe). It was not our day. We leafed through countless birth and marriage records but found nothing. In truth, we had no idea what we were looking for, or where to begin. Our empathetic friends smiled in recognition.

The next day, armed with new resolve, we went on a mission to find Kozia, the street on our parents’ birth certificates (obtained by my brothers a year earlier). No.24 was nowhere to be found. The houses along the short block and a half are either old or decaying, or reduced to a crumbling wall devoured by overgrowth. The house of prayer on the corner had been converted to apartments. A supermarket touted gentrification.

One of several abandoned lots where houses once stood on ulica Kozia.

I remembered my mother talking about the Black Madonna. The Monastery is still as luscious and crowded, but the house where she and her family lived had disappeared with barely a trace. We were pilgrims without a shrine.

I felt the stone pavers under my feet, imagined mom as a child playing with friends, brothers, cousins, walking to and from school, accompanying her mother to the market, the shochet for Holidays. I scoured the area for houses she may have considered while running for shelter after her family was rounded up. Perhaps she returned, betrayed by the farmer who hid the blond, blue-eyed seveteen-year old beauty, in exchange for free labour and the two gold coins her father had hidden in her shoes. I thought of her languishing in HASAG, emaciated, worked to exhaustion. Sadness gave way to anger. It was time to leave.

I spent the last day with friends at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. Sifting through microfiched records kept by the Częstochowa Judenrat between May 1941 and January 18, 1942, I found my grandfather’s name on a list of workers and craftsmen, whose tools had been confiscated for the Nazis.12 His was a sewing machine (Naehmaschine). He did not own a painting store after all!

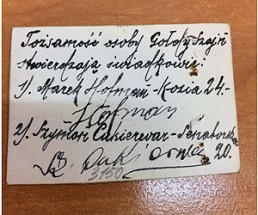

Moszek Hofman’s handwritten Judenrat entry

It bothered me that my grandfather’s was the only handwritten name on the typewritten pages. I set the thought aside. I imagined his sinewed hands working away at the old sewing machine, foot on pedal, his back bent over, the up and down motion of the needle giving life to shapeless cloth. Perhaps he was making a dress for his only daughter. Before I could fully image my mom proudly parading her father’s gift, joy faded into darkness at the realisation that ulica Kozia runs around the corner of the Old Market Square (Stary Rynek) in the Big Ghetto, the gathering place on the way to the train station a mere six blocks further, where her world would soon roll unabated through the gates of hell.

The archivist suggested I look through Częstochowa’s municipal records. Imagine my surprise when I found there an application for an identity card issued to my grandmother on May 31st, 1930. I pointed to the reference to an extant photograph on the microfiche. The archivist examined the screen in disbelief and ran to fetch the original. He returned with a small dark sepia photograph attached to the original yellowing document. The room was abuzz with excitement. I was dumbfounded.

No pictures of this side of the family had survived the War. Had I struck gold? The document revealed my grandmother’s and grandparents’ official first and last names (not the Yiddish ones I was given), the time and place of her birth (not Częstochowa), her avowed profession (worker), the colour of her hair and eyes (grey, like mine).

Front and back of Photo for Golda Hofman’s Identity Card

I searched the photograph for more clues. The young woman staring at the camera was clearly not used to having her photograph taken. Her gaze is stern yet quizzical, her body stiff but relaxed. I had imagined her a babushka. The solid, curious, assertive woman in the short-sleeved and relatively low-cut dress was everything but. I saw hints of my mother in her, my cousin saw her father.

The back of the photograph opened yet another door. My grandfather’s signature, certifying the identity of his 27 year old wife, jumped out at me like a bolt from outer space – a palpable remnant of his physical presence at a specific place in time. I was relieved that the rudimentary scrawl did not match the handwritten entry in that Judenrat list. I wouldn’t want to think of him performing that thankless role. The photograph had had a big impact, but the handwritten name had surpassed the mechanically reproduced image’s immediacy by far. I could smell the paper, touch the protruding ink and, through both, him. It is the closest I ever got to any of my four murdered grandparents.

Guided by the belief that I owe “never again” to my children and their children’s children, when my father died I made the decision to leave the study of the Shoa to historians and other experts and to direct my efforts, instead, to help curb the resurgence of Jew-hatred in the future. I wrote letters and articles, joined organisations, sat on boards, sought out innovative solutions. After eighteen years, all I saw was the multi-headed hydra rising again, safe places dwindling. My trip to Częstochowa was an attempt to understand why.

While that question still begs and answer, I learned that I was wrong to think I could skip the past. Not because it has the nasty habit of returning in different guises. One can live with ghosts forever without knowing it, but healing can only come from fleshing them out, endowing them anew with life through the work of re-remembering, of piecing together fragments of their truncated existence, touching walls, walking on cobblestones, cleaning the moss off gravestones, reaching out beyond dense-dark anxieties and fears to find moments of rest, maybe even deliverance.

We can only mourn a loss we make our own.

My mother, Sura/Sala Hofman, was born and raised in Częstochowa. My parents married in Germany after the War and left for Bolivia, pregnant with me. There, they raised a family, while recovering from undiagnosed and untreated PTSD. They immigrated to Vancouver shortly after I did. Both are buried here.

SUBMIT YOUR OWN STORY!

to learn how!

About the Author:

Elena is an independent scholar, theorist, critic and curator of Film and Media Arts. She holds an M.A. from the University of British Columbia and a PhD in Comparative Literature from Stanford University. She is the author of several articles published in magazines, academic journals and book collections.

Elena is an independent scholar, theorist, critic and curator of Film and Media Arts. She holds an M.A. from the University of British Columbia and a PhD in Comparative Literature from Stanford University. She is the author of several articles published in magazines, academic journals and book collections.

In addition to teaching, she has curated film and video programs and organised conferences, both nationally and internationally, with the support of both the Canada and British Columbia Councils for the Arts, as well as the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. She was Humanities Fellow at Stanford and founder and Executive Director of Americas on the Verge Society for the Advancement of Arts and Culture in Vancouver.

Born in Bolivia, with survivors of the Shoah as parents, she currently resides in Canada. She has served on the executive of the now-defunct, BC Campus Action Coalition, the first Canadian organisation aimed at identifying and supporting efforts to resist the growth of antisemitism on university campuses, also acting as liaison between this organisation and the Canadian Friends of the Simon Wiesenthal Centre.

Her work is increasingly focused on a number of initiatives aimed at curbing the resurgence of antisemitism worldwide.

Author’s Notes:

1 Huberman, who escaped Europe for British-controlled Palestine, founded the Palestine Symphony Orchestra in 1936 (renamed the Israeli Philharmonic in 1948) largely to rescue, in a desperate and undoubtedly heart-wrenching effort, some 1,000 musicians and their families from certain death. In a revival of some sort, Bell chose to play the Brahms Violin Concerto (played for Brahms by Huberman when he was nine) on the recovered Stradivarius with the Częstochowa Philharmonic at the World Society’s Third Reunion in 2009. The world-class Częstochowa concert hall was officially renamed the Bronisław Huberman Philharmonic Hall on that occasion.

2 Research into the history of Jews in the Polish military has barely began. Most joined, if allowed, in response to Zev Jabotinski’s passionate entreat, to flee or to take up arms, in speeches delivered in Warsaw to tens of thousands of beleaguered coreligionists on three separate, historical occasions – 1936, Tisha B’Av 1937 and 1938.

3 A state-sponsored corporation, the acronym “HASAG” stands for Hugo Schneider Aktion Gesellschaft. HASAG Pelcery, Warta, the Raków steel mill, and the Częstochowianka plants where built within Częstochowa. The other two were HASAG Granat Werke in Kielce and HASAG Skarzysko-Kamienna. Each was devoted to a different aspect of the military enterprise.

4 This number was corroborated by the survivors in the last year of the War.

5 It took never more than three hours to “process” each man, woman, and child into one of the ten gas chambers working simultaneously 24/7. Between 800,000 and 1,200,000 unnamed Jews (and an undetermined number of Roma), continuously transferred to Treblinka as the “inventory” dwindled, were gassed, shot, and buried in mass graves at the camp – up to 15,000 per day. Himmler ordered the camp closed in 1943, after the grounds were razed by fires set by heroic inmates led largely by Częstochowa natives. In a partially successful effort to hide all evidence of his crimes from the advancing Soviet Armies, he personally oversaw the exhumation of 700,000 bodies. Inmates, who did the dirty work, witnessed the large heaps of bodies on pyres burning for months. Imagine.

6 The timetable of the death train from Czestochowa to the extermination camp in Treblinka. It departed from the Warta freight station on September 22nd, 25th and 28th, and October 1st, 4th and 7th 1942 at 12:29 pm to reach Treblinka at 5:25 the next morning. At 10 am, when the train was scheduled to leave for Częstochowa, out of the 7,000 people in the transport only a few men chosen by the Germans to work in the camp were still alive.

7 “God, full of compassion” – a prayer for the dead, especially martyrs, with roots tracing back to the 1648 Chmielnicki pogroms.

8 A relative of Bronisław Huberman. The Częstochowa Philharmonic was dedicated to him at the 2012 World Society Reunion.

9 A prestigious tertiary education institution named after a 15th century Polish priest and true Renaissance man.

10 A treasure trove for visitors and researchers alike, the Museum occupies the main floor of a beautifully restored, neo-Gothic palatial mansion built ca. 1910, on the somewhat seedy but central Kateldrana Street. Owned by two or three Jewish families before the War, among them Alon Goldman’s maternal grandfather Jacob Czarnylas, the former home now serves several social functions. The Museum, which covers the entire main floor, was created to permanently house the exhibition Jewish Life in Częstochowa, on tour since 2004. Curated by Prof. Jerzy Mizgalsky and designed by Prof. Andrzej Desperak, it spans three centuries of Jewish contributions to all aspects of life in the city, with particular emphasis on the years following the Nazi occupation and the 20th century events leading up to the War.

11 Częstochowa was reportedly one of three cities in Poland where Jewish Fighting Organizations were set up during the War.

12 Judenrat, a Board of Elders approved by the Nazis, was assigned the job of documenting public events: police reports, robberies, upheavals, fires, lack of public services, etc.

Henry Srebrnik

In Częstochowa - a Return to the Past

by HENRY SREBRNIK (Professor of Political Science, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada)

I’m writing this from Częstochowa (on 23rd July 2017), where I was born 72 years ago.

The city is best known for the Jasna Góra monastery (pic right). Visited by around four million pilgrims per year, it is a shrine to the Virgin Mary. The cloister houses the Black Madonna, one of the holiest icons of the Catholic Church. My wife and I had a close-up view of it on a tour, and it is indeed a magnificent work of art. Photographs don’t capture its splendor.

The city is best known for the Jasna Góra monastery (pic right). Visited by around four million pilgrims per year, it is a shrine to the Virgin Mary. The cloister houses the Black Madonna, one of the holiest icons of the Catholic Church. My wife and I had a close-up view of it on a tour, and it is indeed a magnificent work of art. Photographs don’t capture its splendor.

My parents, native to the city, were freed from a Nazi labor camp by the Red Army in January 1945. We all left Poland in 1946, and I’ve only been back once, forty years ago. Back then, it was a Communist country and tourism was not high on its list of priorities. It was hard to even obtain information about its history, including the Holocaust, in which some 90 percent of the Jewish population was murdered by the German occupiers.

Things are different now, and historical sites are well marked, tourist guides are everywhere, and the history of its once major Jewish community is recognized and even celebrated. Bus tour guides point out the former Jewish ghetto and recount its history.

Częstochowa was an important center of Jewish activity before World War II, and the community prospered.

Częstochowa was an important center of Jewish activity before World War II, and the community prospered.

All this changed on September 3, 1939, when German troops occupied the city. At the time, Częstochowa was home to 29,000 Jews, out of a population of 138,000. Soon enough, the persecution of the Jewish population began.

In August of 1941, the overcrowded Jewish ghetto was hermetically sealed off from the rest of Częstochowa. In 1942, more than 20,000 people were forcibly transferred from neighbouring towns, raising the Jewish population to over 50,000. It turned Częstochowa into the third largest ghetto in conquered Poland after Warsaw and Łódż. Between September 22 and October 7, 1942, most of the city’s Jews were packed into trains and sent to their deaths in the Treblinka death camp.

By 1943, only 3,990 Jews (including my parents) were still alive, all of them working in the HASAG-Pelcery munitions factory as slave laborers.

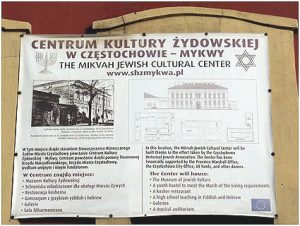

In Częstochowa, where in 1977 it was almost impossible to even locate the Jewish cemetery, there is now a Jewish Museum, opened last year, on Ulica Katedralna. It spans three centuries of Jewish contributions to all aspects of life in the city, with particular emphasis on the 20th century. It also serves as a venue for various events, including academic conferences and reunions of descendants of Częstochowa Jews visiting the city.

The Jewish Social Club (TSKŻ), a community hub, is located at Ulica Generala Jana Henryka Dąbrowskiego. As for the Jewish cemetery, it now includes memorials at the mass graves of Jews killed during the 1943 uprising by the Jewish Combat Organization. My mother’s two brothers were shot by the SS at that time.

We walked around the area that served as the Jewish ghetto during the Holocaust. Among the monuments located there is the Umschlagplatz Memorial on Ulica Strażacka, unveiled in 2009. This was the place, near the Warta train station, from where the city’s Jews were sent to their deaths at Treblinka. The brick monument resembles a ghetto wall on which a large Star of David is mounted and is situated in the spot where daily round-ups and deportations took place. It was designed by the Częstochowa-born artist Samuel Willenberg, one of the last survivors of the 1943 uprising in Treblinka.

At Bohaterow Getta Square, a plaque recalls the members of the Jewish Combat Organization who died fighting the Germans. Ulica Kawia, the site of mass executions of Jews, also has various plaques commemorating some 4,000 murdered victims.

We also went to Ulica Warsawska 13, where my parents had lived before the Nazis, and Aleja Wolnosci 19, where they were housed in 1945-46, after their liberation (along with me, born after the War).

Th e ruins of HASAG-Pelcery still stand, a massive brick and mortar compound on Ulica Filmatów, in an obscure part of the city. A plaque (pic right), in English, Hebrew, Polish,and Yiddish, was placed on an outer wall in 2009 “In memory of the Jews who suffered and died in the German forced labor camp in the Hasag-Pelcery ammunition factory 1942-1945”.

e ruins of HASAG-Pelcery still stand, a massive brick and mortar compound on Ulica Filmatów, in an obscure part of the city. A plaque (pic right), in English, Hebrew, Polish,and Yiddish, was placed on an outer wall in 2009 “In memory of the Jews who suffered and died in the German forced labor camp in the Hasag-Pelcery ammunition factory 1942-1945”.

The ruin looks as sinister and as evil as I would have imagined, like something out of a horror movie.

It’s in an ugly industrial area, there are no signs leading to it, and you can feel the suffering. It was palpable, in the very air, as if the bricks had absorbed the tragedy that had unfolded here.

Perhaps it sums up in graphic form the cataclysm that befell the city’s Jews.

SUBMIT YOUR OWN STORY!

to learn how!

Shosh Koren

A Visit Which Encouraged Me to Do More

by SHOSH KOREN (Second Generation Częstochower and Tour Guide to Poland, Israel)

My Father, Yitzchak Wishlitzky z”l, was born in 1909 in Częstochowa and lived at ul. Warszawska 37. My mother, Chaya (nee Frank) z”l, was born in 1919 and lived in Częstochowa at ul. Garncarska 22. Both survived the War. On the ship “Exodus”, they emigrated to Israel, where had two daughters.

For the past twenty years, I have been leading delegations of youth and adults to Poland, where I have told them my family’s story. I consider this to be very important. By doing this, I am fulfilling the will of my late parents, who always told me to always remember and to never forget.

I think that it is incumbent on all of us to research and document our histories – not just for ourselves, but also for future generations. In doing so, we continue to warn the world that we have not yet learned the lessons of the Holocaust.

In February 2018, I was given the golden opportunity of going to a special educational seminar in Częstochowa thanks to three dear people – Sigmund Rolat, Alan Silberstein and Alon Goldman. The purpose of the seminar was to familiarise ourselves with the history of the Częstochowa Jewish community – from its beginnings to its destruction. It was also intended to raise an awareness of the ongoing encounters between Jewish and Polish youth, which is the result of cooperation between the schools in both Częstochowa and Israel.

This trip gave me the chance for my first visit to the new Częstochowa Jewish Museum at ul. Katedralna 8, which documents the story of the Częstochowa Jewish community. There, we were exposed to stories, some of which I didn’t know at all, further adding to my knowledge.

Also for the first time, I entered the gates of the HASAG forced labor camp, where my parents worked during the War. I saw and felt the place where they suffered hard work, but also the place from which they emerged alive, even though my mother’s two sisters perished there.

Also for the first time, I entered the gates of the HASAG forced labor camp, where my parents worked during the War. I saw and felt the place where they suffered hard work, but also the place from which they emerged alive, even though my mother’s two sisters perished there.

During the visit to the cemetery (pic right,) we found the broken tombstone of my grandfather’s grave, Shlomo David Wishlitzky, who passed away in 1933. Finding it was the result of the excellent work done by the Gidonim group, the Reut students from Jerusalem, led by their teacher Dina Wiener, as well as by Mr. Paszkowski. We held an emotional ceremony next to the grave, with a reading of El Maleh Rachamim and Kaddish. To think that my father was the last survivor of three brothers and one sister. After 75 years, his granddaughter finally visits his grave – who would have believed it???

We then visited my mother’s family home ul.  Garncarska 22. There I spoke about the family hiding in the basement of the house and how they were taken from there during the Aktion which took place on Yom Kippur – 22nd September 1942 – when my aunt Leah, my mother’s sister, and others were sent to their deaths in Treblinka.

Garncarska 22. There I spoke about the family hiding in the basement of the house and how they were taken from there during the Aktion which took place on Yom Kippur – 22nd September 1942 – when my aunt Leah, my mother’s sister, and others were sent to their deaths in Treblinka.

At the end of the seminar, we met the directors and staff of the Museum Archive, where documentation regarding the Jewish inhabitants of Częstochowa can be found. Here, I had quite an emotional surprise – the privilege of seeing the birth certificate of my grandfather, Hanoch Frank, the marriage certificate of my grandparents, the death certificate of grandfather Shlomo Wishlitzky and much more. I showed the archive staff pictures of family members, the people behind these documents.

After the seminar ended, I returned to my home with a clear feeling that I had to go on researching. I needed to restore my grandfather’s gravestone in the cemetery and, with my extended family, I need to share everything which I’d experienced during the seminar.

My parents were allowed to emigrate to Eretz Israel, where they raised a new family and fulfilled their dream – to witness the existence and independence of the State of Israel. This is my family’s sweet revenge over the Nazi enemy, which had tried to exterminate them, but failed. My parents had two daughters – my older sister Michal and me. Michal has five children and thirteen grandchildren. I have three children and seven grandchildren. The more, the better!

I wish to thank all those who helped me, especially to all the Polish staff who accompanied us on the tours, took care of us and who treated us with great respect. Thanks to the instructors who supported, encouraged us and listened to us. Special thanks to Alon Goldman for the opportunity afforded me to join an interesting and instructive seminar that enriched me with great knowledge about the Jewish community which had lived in Częstochowa for centuries. The Seminar achieved its goal!

Adaya Klin

I Will Return to Connect the Dots

by ADAYA KLIN (Second Generation Częstochower, Israel)

My father, David Krakauer, was born in Częstochowa in June 1924. Throughout his life, he tried to tell us his story. Sometimes we listened and sometimes we didn’t. When I grew up, got married and had my children, I began to listen in earnest to his life story. At some point in my life, I joined the staff of instructors at the Ghetto Fighters’ House and, through the guidance of the Museum staff and through young people on trips to Poland, more and more stories penetrated my skin; so much so that the Holocaust has become central to my life.

Long before the passing away of my father and mother-in-law Tosia Klein (nee Krause, who was also born in Częstochowa), Alon Goldman suggested that I join the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel. I declined his offer then. I felt overwhelmed by the evidence and the research.

I then forgot all about it and went on with my life, until a few months ago, when I was asked by Dr.Sharon Geva, a historian who lectures at the Kibbutzim College, to write, in her blog “Women in History” about Dorka Sternberg and the Bram family. Dorka was a very well-loved woman whom I met at the Ghetto Fighters’ House. I entered my father’s name in the blog, mentioning that they had both worked in the HASAG-Pelcery forced-labor camp in Częstochowa.

I don’t know how the article came into Alon Goldman’s possession but, the day after its publication, he sent me a picture of the cemetery mass grave. Engraved among the names on it were members of my father’s family.

Between here and there, my heart didn’t stop beating. As soon as the next trip to Częstochowa was announced, I hurriedly filled out the application form. I went very excited.

I had already visited the city in 1992 with my sister, mother and father, but my memories of that journey are terrible, a true nightmare. My father was agitated and wandered around the city like some ghostly incarnation of Amok. He spoke only in Yiddish and Polish and didn’t see us at all.

This personal trip was to be a correction. This was to be a reunion of a different kind.

The story of Sigmund Rolat, who grew up in the city and spent the Holocaust, and a short time after, in Częstochowa, dovetailed with that of my husband, Giora (Grzegorz) Klein. He also grew up in the city after the War. The photographs and sights in the Częstochowa Jewish Museum, the Ghetto area and the highlight of my visit, the Jewish Cemetery, where I told my family’s story and was able to say Kaddish. I never thought of saying Kaddish or lighting a candle. These are rituals which I never practised in the cemetery at my family’s graves. But the group offered, asked, and I responded. I thank them very much for that.

What surprised me and lingers as an unsolved question – Why did my father not take us to the cemetery in 1992? Why did he run around the city from place to place and not go to the cemetery? After all, both the mass grave and the martyr’s monument, on which his family names are engraved, were erected after the War. This is something which I will never know.

I have no doubt that I will return to the city with my sisters (if they will want to come with me) and reconnect the dots. I don’t have enough words to thank Alon Goldman. Through him, I have learned so much new information about Częstochowa. Thanks to him, I participated in this journey. Thank you, of course, also to Sigmund Rolat and all the people in the city and our supporting group.

It was a once in a lifetime journey.

Jeff Hersch

Another "Birthright" in Poland

by JEFF HERSCH (New Jersey, U.S.A.)

My grandparents grew up in Częstochowa – a small, yet well-known city in southern Poland. It is one of the most important pilgrimage sites for Polish Catholics, being the home of the Black Madonna, in addition to over fifty Catholic churches. Prior to World War II, Jews made up a fifth of the area’s population. But being so close to the border had its consequences: it was one of the first places to quickly fall victim to the German offensive. After enduring the brutal Nazi-occupation for nearly five years, my Grandfather and Grandmother were the only survivors from their respective families in 1945. They vowed never to return to Poland. In November, I decided to visit.

It was cloudy and bright gray all morning. I was lucky enough to be accompanied by my girlfriend, who had met me in Israel after Birthright. We had gone from Tel Aviv to Budapest, and now to Poland. We rode the train for two hours, seeing rural Poland along the way. A Poland that was synonymous with “the old country”, comprised of vast hills, farm animals, and small, colourful houses spread throughout the fields – “The old country”.

The girl at the front desk of our hostel was taken aback when I asked for a train schedule to Częstochowa. “Aside from religious Polish people, I’ve never heard of foreigners visiting that city,” she proclaimed. I explained to her that I was neither Catholic nor looking for some religious enlightenment, but rather I was on a personal journey to my family’s historical roots. As the half-empty train approached Częstochowa, the blue sky began to peek through the clouds and, before we knew it, the sun was out as we came to a screeching halt.

The girl at the front desk of our hostel was taken aback when I asked for a train schedule to Częstochowa. “Aside from religious Polish people, I’ve never heard of foreigners visiting that city,” she proclaimed. I explained to her that I was neither Catholic nor looking for some religious enlightenment, but rather I was on a personal journey to my family’s historical roots. As the half-empty train approached Częstochowa, the blue sky began to peek through the clouds and, before we knew it, the sun was out as we came to a screeching halt.

Prior to leaving New Jersey, my 94-year-old Grandmother gave me the address of her childhood home. The last time she was there was in 1945, after the War, as a young, distraught twenty-something. On a napkin, without hesitation, she drew an impromptu map of her neighbourhood. From the train station, she indicated that her apartment building was only a block away. Katedralna 7 was her address (she even spelled it right). I was in awe as she vividly remembered her neighbourhood from seventy five years before. “There was a market in my building and a bakery across the street”, she described, as she pointed poignantly in the air with her eyes closed. It was incredible to witness. I took her information and confirmed it with a map online. I showed her a street view of the building now in present-day to verify it was still standing. That was enough to make her cry.

Katedralna – the experience quickly became surreal. I soon found myself in the courtyard of her apartment building. I stood there, mostly in silence, taking it all in, while imagining the neighbourhood bustling with life. Unfortunately, I had no knowledge of which actual apartment my Grandma had lived in, but seeing the building was equally significant.

Around the corner was a huge church (pic left), one of the biggest I had ever seen. I immediately recognised the church, not by its immense size, but by its significance in the story of my Grandparents. This was where the Germans had rounded up Jews on September 3, 1939 – “Bloody Monday.” My Grandfather, then 18 years old, was rounded up with his brother and father, and detained in the church. This is the church where Jews were kept for days and routinely shot at with machine guns. I had heard this story, but standing there, trying to imagine the terror endured, was surreal. I can still hear my Grandfather’s voice telling the story, describing his father jumping on top of him and his brother to shield them from the bullets. That was the first of many assaults they encountered.

Around the corner was a huge church (pic left), one of the biggest I had ever seen. I immediately recognised the church, not by its immense size, but by its significance in the story of my Grandparents. This was where the Germans had rounded up Jews on September 3, 1939 – “Bloody Monday.” My Grandfather, then 18 years old, was rounded up with his brother and father, and detained in the church. This is the church where Jews were kept for days and routinely shot at with machine guns. I had heard this story, but standing there, trying to imagine the terror endured, was surreal. I can still hear my Grandfather’s voice telling the story, describing his father jumping on top of him and his brother to shield them from the bullets. That was the first of many assaults they encountered.

As we continued our walk through the neighbourhood, we came across a large memorial dedicated to the Jews of Częstochowa. The brick monument resembled a ghetto wall and stood in the exact spot where daily round-ups and deportations took place. Accompanying the wall was a plaque which read September 22-October 7, 1942, German Nazi occupants deported from this place about 40,000 Jews of Częstochowa and environs to their death in Treblinka gas chambers. Their memory be honored!

As we continued our walk through the neighbourhood, we came across a large memorial dedicated to the Jews of Częstochowa. The brick monument resembled a ghetto wall and stood in the exact spot where daily round-ups and deportations took place. Accompanying the wall was a plaque which read September 22-October 7, 1942, German Nazi occupants deported from this place about 40,000 Jews of Częstochowa and environs to their death in Treblinka gas chambers. Their memory be honored!

I stood at the memorial and was overcome by an existential force. After a minute of standing there, tears flowed uncontrollably. I thought about my own existence, my life and the experiences I call mine. This was the spot where my then 17-year-old Grandmother was separated from her parents and three brothers, and where she became completely alone, aside from having my Grandfather at her side. (He, himself, was only 18.)

I thought about my entire family’s existence – aunts and uncles and cousins and their children – and the fact that they all stem from my two Grandparents. Had either of them perished, my family would have simply ceased to exist. By something that can only be deemed a miracle, they survived six years of hell, while their friends and families were murdered by the hands of the Nazis and their associates. I thought about all of their relatives who perished and imagined how big my family would be today had they all survived.

But most of all, I realised just how amazing it is to be alive and how grateful I truly am to wake up every day. At that moment, I was extremely proud to be Jewish. I recognise that my existence is a way to prove the efforts of those who sought to destroy human life. based on simple differences, unsuccessful.

Visiting Częstochowa was, in fact, a birthright. It is an experience that will stay with me forever.

SUBMIT YOUR OWN STORY!

to learn how!

Lowi, Noa Yalon

My Częstochowa

by NOA YALON LOWI (Israel)

Background

Yosef (Yosek) and Esther (nee Mendelowicz) Fridman both grew up in Częstochowa, in parallel streets, a few minutes walk away.

Yosek was born in 1916 in Częstochowa and lived ul. Garncarska. His father died when he was still quite young (long before World War II). Esther was born in 1917 in Krzepice and, while still a child, her family moved to Częstochowa and lived ul. Targowa.

Yosek and Esther both joined the Gordonia movement, and later, after the Hachshara, immigrated separately to Palestine – Yosek in 1938 and Esther in 1939.

Yosek had six brothers. The eldest, Dubcha (David), was invited to the United States. He emigrated, married and remained there until his death at a ripe old age. All other five brothers perished in the Holocaust, together with his mother and the rest of her family – three brothers and two sisters.

Two of Esther’s brothers, Yitzhak and Chaim, immigrated to Palestine in the early 1930’s. Esther’s illegal immigration to Palestine was financed by her brother Chaim and she remained grateful to him all her life. Another brother, David, survived the HASAG forced labor camp in Częstochowa and immigrated to Israel after the War. All her brothers, her parents and her other relatives perished in the Holocaust.

Yosek and Esther attended a training camp in Givat Ada and, shortly after, moved to Ma’aleh Hahamisha, where they originally intended to go. They then moved to Bnei Brak, where they decided to start a family out of a desire to raise children. During World War II, Yosek enlisted in the British army. In 1945, their daughter Nitzana was born, followed by their son Aviram in 1950.

Yosek and Esther were my grandparents (my mother is Nitzana), I am the Third Generation of the Częstochowa family living in Israel. In July 2017, I traveled with my family to Częstochowa.

My Trip to Częstochowa

My writing has been blocked, Ever since the visit in Poland.

Something has been thrust, something is blocked.

Something is choked inside and won’t come out.

What happened there? We knew all along that the majority of the Granny’s and Grandpa’s families had perished. That wasn’t a surprise.

We knew about the Holocaust.

We didn’t that think we’d discover a happy ending, something which history had forgotten to tell us about.

So, why this freeze? We hadn’t visited any of the extermination camps. We hadn’t seen harsh sights – not extremely harsh.

We simply went to visit the city where they had grown up and which we had been told about. But it actually began with a suffocation almost from the very first moment.

With excitement and sadness, we arrived at Częstochowa. As we approached the station and saw the “Częstochowa” signs through the window of the train, The heart raced, pounding, as tears climbed the throat, commencing their way out. We got off the train.

As I walked, trying to trace the sign I saw from the train to get closer and photograph it (as well as allowing my tears to burst out), We were welcomed by wonderful Małgosia and Marek, our warm and fantastic, guides whom we had hired to show us around all the places which we wished to see. They smiled broadly and warmly at us, as they held out their hands to help us down from the train. We found ourselves smothering our tears, swallowing them in order to greet them nicely, introduce ourselves and thank them for waiting for us with such devotion.

This blend of genuine gratitude and fought-back tears arouse caged anger and frustration. I felt, “I wanted a moment to digest and process it all and to meet you marvelous people five minutes later and not precisely now.

And you were so lovely and generous,you aren’t the source of this anger nor the shoulder to cry on. Thank you and it’s not fair. Why couldn’t you have been late a few minutes?

And so here began the journey to the past, to the city and to its civil registry and archives where the keep the birth certificates. Actually, when Auntie Macha was born and when Grandpa was born, Częstochowa was still under Russian rule and the documents were probably in Cyrillic. So doubts arose as to exact spelling and whether the documents will be found. And also, in those days, the registry was not necessarily done on the actual date of birth at all. This was not very common.

A beautiful, elderly woman arrives, waiting her turn. I wonder if she was born here and if she knew Granny or Grandpa. Maybe they were friends, maybe and maybe and maybe. And even if they would have met. Who knows if they would remember each other and, even if they did, who knows if they would recognize each other, even if I had a picture here with me of them from those days. Still, even if they did know each other, what issues would it raise? So they knew each other.