The Exhibition Album (First Edition)

The Exhibition Album (First Edition)

Below are PDF files of scans of the First Edition of the Album of the Exhibition

THE JEWS OF CZĘSTOCHOWA

EXISTENCE – HOLOCAUST – MEMORY

Thanks to Alan Silberstein for providing these files.

Part 9: Częstochowa at the Turn of the 20th Century (Częstochowa – Przełomu XIX i XX Wieku)

The Exhibits

The Exhibits

"The Jews of Częstochowa"

“One of Poland’s largest and most vibrant Jewish communities lived in Częstochowa up until the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 and the ensuing Holocaust. From the 18th Century, followers of traditional Judaism, Hasidic Jews, and Christians lived together in relative peace. Until its devastation, Częstochowa Jewry was renowned for its religious faith and academic advances. The massive deportations of Częstochowa Jews to the Treblinka death camp, September and October 1942, took a toll of 40,000 victims.

“Let history teach us tolerance, peaceful coexistence of nations and mutual understanding so that we know better our neighbours. Let us create something which will make us think deeply about the past and the future and will loudly announce that the future of Poland and of all other nations should and must be based on mutual understanding and tolerance.”

All photographs

on this page

were supplied by and

are copyright to

Alan Silberstein

They may not be

reproduced elsewhere

without prior permission.

From an Idea to a Reality

From an Idea to a Reality

by Professor Dr. hab. Jerzy Mizgalski

In the late 1990’s, I received a telephone call which completely surprised me. A pleasant sounding voice advised me that I was speaking with a person from Częstochowa, currently living in Venezuela, Professor Elżbieta Asz-Mundlak. She introduced herself as the great-niece of Częstochowa Chief Rabbi Nachum Asz. With great curiosity, I awaited our first meeting.

I suggested that we meet in my home, because my apartment was where my Jewish- related notes, archival material, literature and photographs are stored. I had already concerned myself with Jewish history issues for over ten years.

My extraordinary guest showed a great interest in the work which, together with my now-deceased colleagues, Dr Zbigniew Jakubowski, and Dr hab. Janusz Lipiec, I had undertaken since the early 1980’s.

Professor Asz-Mundlak  (pic right) raised the idea of making a documentary film about her unusual story as well as to describe her search for any traces that remained of her family and the Jewish community, following the tragedy of the Holocaust. Her enthusiasm spread to my colleagues. Jerzy Piwowarski, then Associate Dean of the Art Department of Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa, Jarosław Kweclich, head of that Department, then Archives Director, Elzbieta Surma-Jończyk plus the directors and staff of the Częstochowa Museum all joined into the project.

(pic right) raised the idea of making a documentary film about her unusual story as well as to describe her search for any traces that remained of her family and the Jewish community, following the tragedy of the Holocaust. Her enthusiasm spread to my colleagues. Jerzy Piwowarski, then Associate Dean of the Art Department of Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa, Jarosław Kweclich, head of that Department, then Archives Director, Elzbieta Surma-Jończyk plus the directors and staff of the Częstochowa Museum all joined into the project.

The intensity of my work on this project led me to search the Public Archives in Częstochowa, Kielce and Łódz, the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, as well as the Archiwum Akt Nowych (New Records Archive) of Warsaw. As the data collected grew, the information gathered regarding the Jewish community of Częstochowa in the 19th and earlier 20th centuries broadened.

Together with Elzbieta, we came to the conclusion that the subject required wider study and was of such interest that it could not be accurately represented in just one film.

Elżbieta made her documentary film entitled “I Was Lucky: A Lesson in History”. In the film, she presented the dramatic circumstances of her childhood when, as a little girl from the Jewish ghetto, she found protection with the Nazarene Sisters and then with the Catholic Częstochowa Zieliński a family.

During Elżbieta’s next visit to Częstochowa, I had the pleasure to meet with another former Jewish resident of Częstochowa who, like her, had the good fortune to have survived the hell of the ghetto and HASAG. Sigmund Rolat (pic left) and his cousin, Alan Silberstein (pic right), were extremely interested in the research material that we had collected and acquainted themselves with our planned project – a museum exhibition which, at the time, went under the working title of The World of Nachum Asz. From that meeting, the work took on an even greater tempo and the scope of the endeavour changed.

During Elżbieta’s next visit to Częstochowa, I had the pleasure to meet with another former Jewish resident of Częstochowa who, like her, had the good fortune to have survived the hell of the ghetto and HASAG. Sigmund Rolat (pic left) and his cousin, Alan Silberstein (pic right), were extremely interested in the research material that we had collected and acquainted themselves with our planned project – a museum exhibition which, at the time, went under the working title of The World of Nachum Asz. From that meeting, the work took on an even greater tempo and the scope of the endeavour changed.

Sigmund turned out to be an amazing man who, as a Częstochowiańin, was visiting his home city after many years and was treating his stay, not only as a return to memories and to his childhood and youth, but also as an opportunity to concern himself with everything that was happening today in Częstochowa. There were many emotional moments. For me, the most inspirational were my discussions with him.

The work surrounding the undertaking “The Jews of Częstochowa – Coexistence, Holocaust, Memory” attracted the interest of the city authorities who offered assistance in various ways. In discussions with students, either privately or with students and teachers in schools, I was bombarded with questions about how the preparatory work on the Exhibition was progressing. Sometimes, it gave me the feeling that this was the next “miracle” under Jasna Góra of John Paul II’s – that two communities, Christian and Jewish, together were creating reflections of their common city’s history.

This reflection on the past became a point of departure for us, who were required to reflect more deeply. Documentary evidence of events and historic facts would determine the narrative of the coexistence, the tolerance and the inter-penetration of cultures as conditioning factors on the progress of civilization. Extensive research in archives and libraries, especially that undertaken in Częstochowa, would answer the basic question:

which had co-existed here for over 200 years?”

“What is the current relationship of the inhabitants of Częstochowa to the Jews, especially those who,

due to the tragic years of the Holocaust, left never to return?”

A meeting of history with the current situation became a lesson for those Jews who arrived from around the world as well as for contemporary Częstochowiańin. Those who, with ill-will hovered here and there in oral history, had to give way to a rational view of relations between the two nations – Polish and Jewish.

“Days of Remembrance – The Jews of Częstochowa”, cultural events created in this city for the first time on so wide a scale after the great tragedy of the Holocaust, would serve the idea of building future societies on foundations of the memory of past historical events. Mutual recognition, as regards to past Częstochowa communities, both Polish and Jewish, was the thread that determined coexistence and tolerance.

The three days (21st-23rd April 2004) of cultural events, meetings and remembrances were something more for the Jewish visitors from all continents of the world, whose family-roots and even childhood is united “from under the cloisters of Jasna Góra” with the city, with the centre of Catholic religious life in Poland and known as such worldwide.

The three days (21st-23rd April 2004) of cultural events, meetings and remembrances were something more for the Jewish visitors from all continents of the world, whose family-roots and even childhood is united “from under the cloisters of Jasna Góra” with the city, with the centre of Catholic religious life in Poland and known as such worldwide.

It was a return to the years of their youth and their childhood, when they still felt the care of their mothers, fathers, times with brothers, sisters, cousins, traditional family gatherings during Jewish religious holidays. Streets, houses, the Jewish cemetery – all evoke memories that are painful – of what has gone forever.

I also had the honour to edit the Exhibition’s album in cooperation with other staff of the Jan Długosz University, the State Archives in Częstochowa and the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, who collected the material for the exhibition itself. Together with the exhibition, the album provides an overall essence. Each of its parts correspond with the arrangement of the material displayed in the exhibition.

I also had the honour to edit the Exhibition’s album in cooperation with other staff of the Jan Długosz University, the State Archives in Częstochowa and the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, who collected the material for the exhibition itself. Together with the exhibition, the album provides an overall essence. Each of its parts correspond with the arrangement of the material displayed in the exhibition.

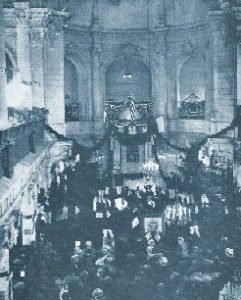

At 4.00pm, in Św.Stasic Park, in the exhibition hall of the Museum of Częstochowa, the exhibition, “The Jews of Częstochowa” was opened. It was a co-operative effort between the staff of the Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa, the State Archive in Częstochowa, the Museum of Częstochowa and the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

At 4.00pm, in Św.Stasic Park, in the exhibition hall of the Museum of Częstochowa, the exhibition, “The Jews of Częstochowa” was opened. It was a co-operative effort between the staff of the Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa, the State Archive in Częstochowa, the Museum of Częstochowa and the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

The exhibition’s Official Opening was attended by many honoured guests. Among those gathered inside and in front of the building’s entrance were many conference attendees and a great number of city’s residents.

Written by:

Prof. Dr. Hab. Jerzy Mizgalski

Historian,

former Vice-Chancellor of the

Jan Długosz University and

one of our Exhibition’s creators.

How It Began

"The Jews of Częstochowa - Coexistence, Holocaust, Memory"

How It Began

Following its opening during our First World Society Reunion in April 2004 in Częstochowa, the Exhibition went on show in Poland’s capital, Warsaw in the following October. A travelling version of the Exhibition subsequently visited cities in the United States of America and in Canada.

Following its opening during our First World Society Reunion in April 2004 in Częstochowa, the Exhibition went on show in Poland’s capital, Warsaw in the following October. A travelling version of the Exhibition subsequently visited cities in the United States of America and in Canada.

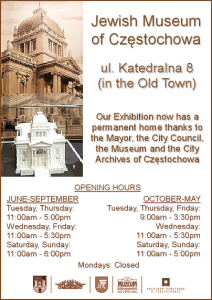

The full exhibition then temporarily went into storage until it found a permanent home in the Jewish Museum of Częstochowa at ul. Katedralna 8.

The original idea of creating such an exhibition came from a granddaughter of Rabbi Nachum Asz (a leader of the Jewish community of Częstochowa in the early 1900’s), Professor Elizabeth Mundlak, who had for years been active in the Polish Association of the Children of the Holocaust. Her idea was supported by Prof. Dr. hab. Jerzy Mizgalski, a historian and a former Vice-Chancellor of the Jan Długosz University of Częstochowa.

The Exhibition traces the history of Częstochowa’s Jewish community, from the beginning of the nineteenth century, through the tragic years of WWII, to the post-War period. The many photographs and precious objects come from state and private collections, both from Poland and abroad.

The Exhibition traces the history of Częstochowa’s Jewish community, from the beginning of the nineteenth century, through the tragic years of WWII, to the post-War period. The many photographs and precious objects come from state and private collections, both from Poland and abroad.

Numerous photographs are reprints from Czenstochower Yidn published in New York in 1947. The Exhibition includes documentary films based on the memories of Holocaust survivors Sigmund A Rolat and Elizabeth Mundlak, as well as many others.

Funded by Sigmund Rolat and Alan Silberstein, the Exhibition was put together utilising the resources of the Pedagogical Institute of Częstochowa, the Częstochowa Municipal Archives and the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw.

From the Exhibition’s Sponsor, Sigmund A. Rolat ….

I was a Pole whose religion happened to be Jewish. And then came the rude awakening. During the War, the Germans declared Jews to be “Untermenschen” and our Polish compatriots, with some notable exceptions, were passive or worse.

I was a Pole whose religion happened to be Jewish. And then came the rude awakening. During the War, the Germans declared Jews to be “Untermenschen” and our Polish compatriots, with some notable exceptions, were passive or worse.

The horrors continued after the War. In 1946, there was the Kielce pogrom and random violence in other places. In 1968 – the coup de grace – Poland lost her Jews as a result of the communist government’s so-called “Anti-Zionist Campaign”.

I was lucky to have immigrated to the USA where I proved, as millions before and after me have done, what America is all about. A young, penniless, orphaned boy, willing to apply himself, can receive the best education, prosper in business and secure a solid place in society for his family. Only in America!

But my roots are here, I am a Jew from Częstochowa. I wish my city well. May it prosper and grow.

I salute all those wonderful people who turned a wish into a reality starting with Prof.Berdowski, Prof.Mizgalski and former City Mayor Tadeusz Wrona.

I am grateful to Elizabeth Mundlak Asch, Elżbieta Surma-Jończyk, Janusz Jadczyk, Jan Jagielski, Ireneusz Kozera, Prof.Jarosław Kweclich, Prof.Tadeusz Panecki, Mark Shraberman, Dr.Dove B.Schmorak and especially to my dear Piotr Stasiak for their untiring work and countless hours. My cousin, Alan Silberstein, and I are proud to be part of this distinguished team.

I trust that all who view the Exhibition, and the book that depicts its exhibits, old and young – especially the young – will shed a tear for the once-vibrant community that is now reduced to a tiny handful.

Our Exhibition

Our Exhibition

The first volume of a biographical guide to the Jewish Cemetery of Częstochowa has been published by the History of Częstochowa Documentation Centre of the Museum of Częstochowa.

The book contains a register of identified tombstones, short footnotes about the deceased and detailed biographies of more notable people buried in this necropolis. War-graves have been specifically highlighted. The guide also contains information about graves where, today, tombstones no longer exist or where the engraving on existing tombstones has completely eroded.

The book contains a register of identified tombstones, short footnotes about the deceased and detailed biographies of more notable people buried in this necropolis. War-graves have been specifically highlighted. The guide also contains information about graves where, today, tombstones no longer exist or where the engraving on existing tombstones has completely eroded.

This book is the first attempt at such a study. The authors have used both library and archival sources. They have collected data from both Polish and Jewish periodicals as well as works in Polish, German and Yiddish.

They also took advantage of a Polish inventory carried out in 1970-1975. At that time, every gravestone received its own number, however that inventory only listed the Polish-language inscriptions. In 1997, coordinated by Benjamin Yaari, a group of young Israelis, together with Martyna Strachel, Ada Holzman, Uri ben Zion and Michael Chen, listed over 2,000 monuments. Unfortunately, this work was incomplete, contained many errors and inaccurately recorded many names and dates. The authors of this guide have also utilised the results of both inventories.

Due to time constraints and the difficult or impossible access to many graves, the authors’ research within the cemetery itself has been limited. It did allow them, however, to correct and supplement the existing inventories.

This is the first attempt at work on this topic, because published material is limited and, not infrequently, in a “raw” state. The guide will, however, be continued in the form of a second edition or even a second part – depending upon how it is received by its readers and upon whether there is a demand for further work.

For this reason, we are asking for information to be sent to us about people buried in the Jewish Cemetery of Częstochowa, as well as photographs of both the people and also of their tombstones (if available). We also request information about the history of the cemetery itself.

| Our Address: Muzeum Częstochowskie Ośrodek Dokumentacji Dzieów Częstochowy, al. NMP 45a 42-200 Częstochowaemail: oddc@o2.pl |

The Authors:

Dr.Julius Sętkowski is an historian, having studied the 1905 Revolution. He is the author of monographs about the fighting-organizations of the Polish Socialist Party in the Częstochowa district and is also the author of two guides on the Częstochowa Catholic Cemeteries on Kula Street (including the sections of other faiths contained therein and the Evangelical Church section in Roch Street). He works at the Museum of Częstochowa, is Director of the History of Częstochowa Documentation Centre and heads the editorial team which is prepared the expansive “Encyclopaedia of Częstochowa”.

Wiesław Paszkowski was on the team to that prepared both the album “The Jews of Częstochowa – Coexistence, Holocaust, Memory” and the exhibition “The Jews of Częstochowa”. He is the author of articles on the history of Jewish education in Poland and on the state of research into the extermination of Częstochowa Jews. He works at the Museum of Częstochowa.

Our Exhibition

Our Exhibition

"The Jews of Częstochowa - Coexistence, Holocaust, Memory"

This section of our website tells the story of our exhibition which, after travelling around the world, finally in 2016, found a permanent home in the Jewish Museum of Częstochowa – thanks to the Częstochowa Mayor and City Council. More information about the Jewish Museum can be found here HERE.

This section of our website tells the story of our exhibition which, after travelling around the world, finally in 2016, found a permanent home in the Jewish Museum of Częstochowa – thanks to the Częstochowa Mayor and City Council. More information about the Jewish Museum can be found here HERE.

Unlike many exhibitions about the history of Jews in Poland, our exhibition, while of course covering the tragic period of Holocaust, places specific emphasis on how the Jews of Częstochowa lived, not just how and where they died. This is particularly important for two groups of visitors to the Museum:

- The descendants of the Jews of Częstochowa, who have read, seen and heard so much about how and where their ancestors perished, can now see how these ancestors of theirs lived and can also understand the contribution which they made to the city Częstochowa and also to Polish life.

- Polish young people, today, live in a country which is 90-95% mono-cultural. It is easy for them to think that it was always like this when, in fact, prior to World War II, Poland was probably the most multi-cultural country in the whole of Europe. They need to learn and understand that among this ethnic mixture, Jews in Poland made up 10% of the total population and, in Częstochowa, 30% of its inhabitants were Jews.

This section covers how the exhibition came to fruition. It features the people who made it a reality through vision and determined effort. It also shows how the exhibition travelled the world before it finally found its permanent home in Częstochowa.

This exhibition is one major legacy which we can leave to our future generations. It is almost a self-evident truth that to understand who you really are, you need to understand where you come from. Through the exhibition we commit to that truth and, in doing so, we preserve the history and memory of those who came before us and can no longer tell their own story.

Professor Dr. hab. Jerzy Mizgalski

"Why Am I Interested in the History of the Jews of Częstochowa?"

by Professor Dr. hab. Jerzy Mizgalski

I am often asked this and similar questions. Sigmund Rolat also asked me this question on 3rd November 2005 at the history symposium connected to the opening of the Jews of Częstochowa exhibition in the Polish Consulate-General in New York. I will answer this question here in the same way that I answered in New York.

It all began when I was searching through various Polish archives for material relating to education at municipal government level during the time of the Second Polish Republic. I ascertained at that time that, among many stored archival documents, there were documents confirming wide-scale educational activities conducted by Jews.

During discussions with my late colleagues, Dr. hab. Janusz Lipiec and Dr. Zbigniew Jakubowski, we decided to examine the issue of Jewish education within the Second Republic.

THAT WAS EASY ENOUGH TO SAY – BUT WHERE TO BEGIN?

From preliminary research, I realised that, at that time (beginning of 1990), very little had been written in the Polish language on this subject. I ended up at the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw. There, I met a wonderful man – Zygmunt Hofman. After long discussions with Zygmunt, I was convinced that this very complex issue could not be researched without a deeper study of Jewish history and culture.

The death of Zygmunt Hofman and, later, Janusz Lipiec and Zbigniew Jakubowski, motivated me to even more intensive work. Zygmunt Hofman and Janusz Lipiec, despite their advanced years, and Zbigniew Jakubowski, despite his severe illness, remained extremely enthusiastic for the work until the end of their days. They regarded the statement, preserving memory, not as a short-term slogan, but as a program of serious research.

Janusz Lipiec, a fighter in the Polish underground (ZWZ AK) during the years of Nazi occupation, a prisoner in Pawiak prison, in the concentration camps in Auschwitz and Dachau, strongly reminded me, daily, that the history of Polish Jews is a part of the history of Poland and that the Holocaust was the greatest crime of recent history.

This was a tragedy for the Jewish people and an enormous loss for the whole civilised world, including Poland. The contribution of Jews to the development of the civilised world and to the Polish state cannot be forgotten. To show the truth about Jewish communal life in Poland before the Holocaust is an obligation we owe to those Jews who survived the hell of World War II, something we also owe to the Polish people who, for centuries, welcomed into their land the descendents of King David.

As years went by, I coyly published the results of my research in humble articles. I was concerned, and am still concerned, as to whether I am interpreting the archival documents accurately. Raised within Catholic culture, I neither knew nor understood how Jewish religious traditions are so strongly tied to Jewish daily life.

A NEW MOTIVATION

A visit to Częstochowa by the great-niece of Chief Rabbi Asz, Professor Elżbieta Mundlak (pic right), gave me a new motivation for the work. Cooperating in the preparation of Elżbieta’s documentary film, I Was Lucky, caused me to research deeply into the history of Częstochowa’s Jewish community. However, the amount of gathered material far exceeded the amount which could be utilised in just one documentary film.

A visit to Częstochowa by the great-niece of Chief Rabbi Asz, Professor Elżbieta Mundlak (pic right), gave me a new motivation for the work. Cooperating in the preparation of Elżbieta’s documentary film, I Was Lucky, caused me to research deeply into the history of Częstochowa’s Jewish community. However, the amount of gathered material far exceeded the amount which could be utilised in just one documentary film.

A small project then arose under the working title of The World of Rabbi Nachum Asz”. The exhibition displayed the life of Częstochowa’s Jewish community before the Holocaust. Rabbi Asz (pic left), who was a rabbi in Częstochowa for more than 40 years, died in 1936.

A small project then arose under the working title of The World of Rabbi Nachum Asz”. The exhibition displayed the life of Częstochowa’s Jewish community before the Holocaust. Rabbi Asz (pic left), who was a rabbi in Częstochowa for more than 40 years, died in 1936.

His world, namely life in Częstochowa, was the life of a city in which Poles and Jews lived as neighbours. The Jewish community underwent social and cultural changes at the turn of the twentieth century. The intensification of these changes during World War I and during the rebirth of the Polish state made for some very interesting research.

A variety of cultural life together with social and political diversity among the Jews indicated a lively Częstochowa Jewish community before the tragedy of the Holocaust.

A variety of cultural life together with social and political diversity among the Jews indicated a lively Częstochowa Jewish community before the tragedy of the Holocaust.

Elżbieta introduced me to Sigmunt Rolat (pic right), a Jew formerly from Częstochowa. The result of these discussions was the birth of the idea to create a larger exhibition The Jews of Częstochowa.

SO, TO ANSWER THE QUESTION … why I chose this subject of research, I can state:

1. To better understand others and myself.

2. To try, as much as possible, to accurately explore the life of the generation which preceded my own generation.

3. To draw attention to the fact that multiculturalism and life with multicultural tolerance is too little. It is still possible to live side by side and still not understand each other.

4. Transcultural recognition and understanding the differences also helps me to recognise and understand my own culture – the one in which I grew up. I am a Pole. My grandparents and parents were Catholics with a deep faith. I grew up in this culture. I am also a believer and, in accordance with the historic words of John Paul II about “older brothers in faith”, the culture and life of this society deserves to be recognised, having lived together with my grandparents’ and parents’ generations. Together, they built a future for their children and grandchildren.

5. In order to better recognise and understand the tragedy of the Holocaust. It is too little to merely speak and write about it. We must acknowledge this world which was destroyed by the Holocaust, the huge contributions to life made by entire generations of Jewish families, their contribution to the culture of the world, to Poland, as well as to my own city of Częstochowa and its surroundings; a society which was the target of not only annihilation, but also attempts to wipe it from the world’s memory. The Exhibition, as well as the Album, endeavours to show the spiritual and material richness of Częstochowa Jewish society that was brutally interrupted by the Holocaust. We have divided it into several sections which have been clearly designated in both editions of the Album The Jews of Częstochowa. This kind of concept better depicts the multifaceted and varied richness of Częstochowa Jewish society. What remains today is not quite 200 Jews living in Częstochowa. Centred around their cultural association, social gatherings take place once a month. Before World War 2, the Jews represented one-third of Częstochowa’s inhabitants.

6. To provide today’s young generation with a picture drawn from the many broken threads of life of generations of families living with their own traditions and culture, but which also contributed much materially and culturally to our city, region and country. Ideological blindness (the only explanation of the facts), which I clearly document, causes homo sapiens to not only disregard another person, but to also endeavour to destroy his traditions and culture and to eliminate him from memory with ideological slogans. Hostility, built upon the subsoil of this ideology, is close to the tragedy of the Holocaust. For the present generation of the 21st Century, I consider this message to be the most important. No ideology or religious interpretation and justify this outrage against humanity.

May the destroyed lives of the victims of World War II cause us to reflect and serve as a warning. A major reason for researching a culture is to serve as a warning, to all ideologues and politicians, that human life combines not only one’s own life, but also one’s society and that of one’s nation.

The divine commandment that thou shalt not kill applies to all religions and to all societies.

The article on this page

was written by

Prof. Dr. Hab. Jerzy Mizgalski

Historian,

former Vice-Chancellor of the

Jan Długosz University and

one of our Exhibition’s creators.

Rabbi Nachum Asz

Rabbi Nachum Asz

-Chief Rabbi of Częstochowa

The Gaon of Częstochowa

Rabbi Nachum Asz was born in 1858 in Grodzisk, near Warsaw, His father, David Hersz, was a renowned Talmud scholar. On his mother’s side, his grandfather, Leon Landau, was the author of several religious books.

Rabbi Nachum Asz was born in 1858 in Grodzisk, near Warsaw, His father, David Hersz, was a renowned Talmud scholar. On his mother’s side, his grandfather, Leon Landau, was the author of several religious books.

Already as a teenager, when Nachum Asz studied at the famous Talmud school of Rabbi Lewental in Kole, he was known as an extremely clever student.

The next step was the school of Rabbi Samson Arensztajn, the Rabbi of Kalisz. There, Nachum Asz received the title of Rabbi and married Rabbi Arensztajn’s daughter, Sara. Nachum Asz obtained his first rabbinical position in Nieszawa, a position he held for several years.

In 1889, at the age of 31, Nachum Asz was called to the position of Rabbi of Częstochowa. For 47 years, until the time of his death in 1936, he held the position of the city’s Chief Rabbi and was the pride and joy of the Jewish community of Częstochowa.

A very wise man, he chaired the Court of Arbitration and also produced several religious books in Yiddish and Hebrew. At the same time, he was active in communal life and was known throughout Poland.

A very wise man, he chaired the Court of Arbitration and also produced several religious books in Yiddish and Hebrew. At the same time, he was active in communal life and was known throughout Poland.

In the last years of his life, a major problem arose with the threat of forbidding ritual (Kosher) slaughter in Poland. An antisemitic front, headed by parliamentarian Janina Prystorowa, with the participation of Father Trzeciak as an “expert” on Talmud, proposed that the Sejm (Parliament) issue a law forbidding ritual slaughter. Only one Talmud scholar, Professor Tadeusz Zaderecki, stood in defence of the Jewish proposition that ritual slaughter was, in fact, “humane”.

Rabbi Asz (his signature, pic left) took an active role in defence of ritual slaughter. With the help of two of his sons, in 1935 he published a book entitled In Defence of Ritual Slaughter. The book was a great success. The Jewish Community Council of Warsaw published a second edition which it distributed to all members of the Sejm with the aim of presenting the arguments from the Jewish point of view.

Rabbi Asz (his signature, pic left) took an active role in defence of ritual slaughter. With the help of two of his sons, in 1935 he published a book entitled In Defence of Ritual Slaughter. The book was a great success. The Jewish Community Council of Warsaw published a second edition which it distributed to all members of the Sejm with the aim of presenting the arguments from the Jewish point of view.

The Jewish Community Council of Częstochowa then published a third edition of the book. Rabbi Nachum Asz was now famous throughout Poland.

As Gaon, Nachum Asz was in constant contact with the Bishop of Częstochowa, Teodor Kubina. At the same time, he was also Chaplain to the Polish Army garrison stationed in Częstochowa.

Highly learned, he was interested in both Jewish and international affairs. As a member of Mizrachi, a religious-Zionist party, he was one of the first great Polish rabbis to accept Zionist ideology at a time when the majority of Orthodox rabbis were against it.

In 1904, as President of the Committee to Aid Pogrom Victims, Rabbi Asz busied himself raising money. So as not to embarrass the people who were helped, he proposed that the money be distributed in the form of loans, as opposed to charity. When asked why, Rabbi Asz replied that, according to our religion, the most important thing was to help people – not merely to give charity – and in any case, no one would worry about the money being repaid. It was a question of honour – it would be easier for people to accept a loan rather than charity.

In 1904, as President of the Committee to Aid Pogrom Victims, Rabbi Asz busied himself raising money. So as not to embarrass the people who were helped, he proposed that the money be distributed in the form of loans, as opposed to charity. When asked why, Rabbi Asz replied that, according to our religion, the most important thing was to help people – not merely to give charity – and in any case, no one would worry about the money being repaid. It was a question of honour – it would be easier for people to accept a loan rather than charity.

As an influential personality, Rabbi Asz raised considerable funds for both Keren Hayesod and Keren Kayemet, zionist charitable foundations.

In 1934, he founded and chaired the committee to raise funds for the rebuilding of the 100-year-old religious Beit Hamidrash school. Shortly after his death, in recognition of his contribution and efforts, the Jewish Community Council directed that the new school be called Ohel Nachum.

Rabbi Asz took a large role in the building of Hachnasat Orchim – a refuge for the extremely poor, within which was also a religious school and prayerhouse.

In the 1920’s, a new mikvah was built (pic right) – again at the instigation of Rabbi Asz.

In the 1920’s, a new mikvah was built (pic right) – again at the instigation of Rabbi Asz.

In 1925, numerous celebrations were organised to mark the opening of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. In Częstochowa, Rabbi Asz delivered a speech in Hebrew and a brochure containing his teachings in Yiddish was published to mark the occasion.

During the time of his governance, the Rabbi solved numerous and important disputes between Jewish secular and Orthodox groups, and performed thousands of religious and scholarly activities. His pronouncements always carried a high moral value.

His brother-in-law, Rabbi Moshe Halte (pic left) , was also a renowned Talmud scholar. He chaired the Chevra Kadisha – an organisation which dealt with Jewish burials. Rabbi Asz was also the cousin of Nachum Sokolow, the chairman of the World Zionist Organisation and also a distant relative of the famous writer, Shalom Asz.

, was also a renowned Talmud scholar. He chaired the Chevra Kadisha – an organisation which dealt with Jewish burials. Rabbi Asz was also the cousin of Nachum Sokolow, the chairman of the World Zionist Organisation and also a distant relative of the famous writer, Shalom Asz.

Rabbi Asz left nine children – five sons and four daughters. A pious man, he was also tolerant and permitted his children to undertake “worldly” studies. In those days, this was extremely rare. One daughter became a teacher, one son became a journalist and another son became a Doctor of Laws and a Czestochowa City Councillor.

Rabbi Asz left nine children – five sons and four daughters. A pious man, he was also tolerant and permitted his children to undertake “worldly” studies. In those days, this was extremely rare. One daughter became a teacher, one son became a journalist and another son became a Doctor of Laws and a Czestochowa City Councillor.

Rabbi Asz died on 12th May 1936. He went to the synagogue for a memorial service to mark the first anniversary of the death of Marshal Jozef Piłsudski. Perhaps moved by the emotion of the occasion, Rabbi Asz suffered a heart attack and, within a few hours, he tragically passed away. His passing was greatly mourned amongst the Jewish community. His funeral was huge event.

Rabbi Nachum Asz was a great personality. He presided over the religious Jewish community of Częstochowa for forty seven years (1889-1936) – right up until his death at the age of 78.

Source:

The Webmaster gratefully

acknowledges the help of

SEVEK GRUNDMAN

and his daughter

JOELLE

in creating this

tribute page.

The "New Synagogue"

The "New Synagogue"

The Haskalah Movement

The Haskalah (“Enlightenment”) mov

The Haskalah (“Enlightenment”) mov ement had its origins in Germany in the mid-18th Century. It had, at its core, an emphasis on Western culture, use of Hebrew instead of Yiddish, a love of Israel, and it encouraged the study of secular subjects. It is also credited with laying the groundwork for the eventual Zionist movement.

ement had its origins in Germany in the mid-18th Century. It had, at its core, an emphasis on Western culture, use of Hebrew instead of Yiddish, a love of Israel, and it encouraged the study of secular subjects. It is also credited with laying the groundwork for the eventual Zionist movement.

The Jews who came from nearby Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries and settled in and around Częstochowa, including the founders of the kehillah, brought with them the spirit of the Haskalah. In the late 19th Century, the more affluent of Częstochowa’s Jews moved away from the traditional Jewish quarter to the city’s centre, around I Aleja Najświętszej Marii Panny.

It is in this area, in 1893, that they built the New Synagogue, on the corner of ul. Wilsona (formerly ul. Aleksandrowska) and ul. Garibaldiego.

Due to its style of architecture, the presence of a male-voice choir, the dress of its clergy, the more modern pronunciation of the Hebrew prayers and its Haskalah philosophy, the New Synagogue came to be known within Częstochowa’s Jewish community as the Deutscher Shule (“German Synagogue”).

The Height of Chazanut

In accordance with the ideas of the Haskalah or Jewish Enlightenment, the New Synagogue sought to combine secular knowledge with religion. They chose outstanding scientists and scholars to be religious leaders,such as the historian Mayer Balaban.

In accordance with the ideas of the Haskalah or Jewish Enlightenment, the New Synagogue sought to combine secular knowledge with religion. They chose outstanding scientists and scholars to be religious leaders,such as the historian Mayer Balaban.

In 1903, as its first Chazan (Cantor), the New Synagogue apppointed Reb Abraham Birnbaum – a great coup as Cantor Birnbaum already had a great reputation throughout Europe for his Chazanut.

During his tenure, which ended in 1923, Cantor Birnbaum established a renowned cantorial school at the New Synagogue. Its graduates found success and admiration in the United States. He was also the first person to start a Union of Cantors. In his compositions. Cantor Birnbaum combined traditional Jewish themes with the elements of contemporary European music.

In 1923, Reb Avraham Fiszel (pic right) became the New Synagogue‘s Chazan. He lived with his family in an apartment on the synagogue premises.

In addition to his duties as Chazan, Reb Fiszel taught music at the Jewish high school and was instrumental in the formation of numerous Jewish choirs in Częstochowa.

After the Nazis set fire to the New Synagogue, Reb Fiszel decided to remain, living in a small shack in the synagogue courtyard, where he continued to perform his duties as best he could.

According to some historians, Reb Fiszel perished in Treblinka in 1942. However, other accounts tell the story of how, when he was caught conducting services by the Nazis, he was made to run through the streets in front of a Nazi motorcycle. When he was exhausted and could run no further, he was stood up against a wall and was shot.

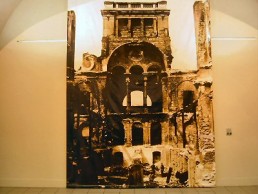

Destroyed by the Nazis

On Christmas Day, 25th December 1939, the New Synagogue was set on fire by German military policemen, assisted by their Volksdeutsch henchman.

On Christmas Day, 25th December 1939, the New Synagogue was set on fire by German military policemen, assisted by their Volksdeutsch henchman.

The Judaic library, with its rich music collection, was decimated along with the building itself.

After the Nazis had left, it has been reported that Reb Fiszel, together with three others (Gliksman, Mitz and Dawidowicz) entered the synagogue ruins and saved whatever they could.

It is quite possible, that the New Synagogue‘s Aron Ha’Kodesh, which has been held in the Jewish Historical Institute’s Warsaw warehouse until this very day, is still in existence only due to the daring efforts of these four individuals.

Until his death (whether at Treblinka or in the streets of Częstochowa), Reb Fiszel continued to conduct services in the basement of the ruins of the New Synagogue.

Today …

Sadly, Częstochowa’s New Synagogue only stood for 46 years, before its destruction by the Nazis.

Sadly, Częstochowa’s New Synagogue only stood for 46 years, before its destruction by the Nazis.

Today, on the corner of ul. Wilsona and ul. Garibaldiego, where the New Synagogue once proudly stood as a symbol of Częstochowa Jewry, stands the Bronisław Huberman Częstochowa Philharmonic Concert Hall, home of the Częstochowa Philharmonic Orchestra.

Given this site’s historical significance to the Jews of Częstochowa, it is more than fitting that this building has been named after world-famous violinist Bronisław Huberman, a Częstochowa Jew and founder of the Palestine Symphony Orchestra (comprised of Holocaust escapees) and which today is known as the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra. This building hasalso been the focal point for many of the activities which have takenplace during our Reunions in Częstochowa.

While the New Synagogue stands no more, it is a little melancholic that, even today, when performances of various kinds are advertised for this venue, occasionally the venue is still referred to as The Synagogue.

The "Old Synagogue"

The "Old Synagogue"

Background

The earliest evidence of the presence of Jews in Częstochowa dates back to the 17th Century and is found in the reports of the royal inspections from the years 1620 and 1631.

The earliest evidence of the presence of Jews in Częstochowa dates back to the 17th Century and is found in the reports of the royal inspections from the years 1620 and 1631.

A separate Jewish Religious Community was established in 1808, when the Calisian Department gave its permission to create the community in Old Częstochowa.

The exact date of the start of the construction of the Old Synagogue (Stara Synagoga) at ul Nadrzeczna 32 is unknown. The building was expanded in 1872 and then renovated in 1928-29.

It was ransacked by the Germans in September 1939, who then competely destroyed it during the liquidation of the Small Ghetto in 1943.

The Artist

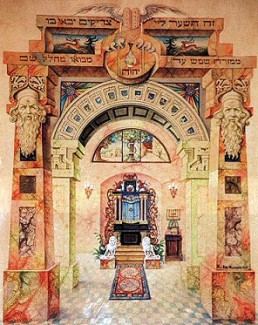

At the instigation of Harav Reb Nachum Asz – Częstochowa’s Chief Rabbi, Professor Perec Willenberg designed the new ornate interior for the renovation of the Old Synagogue which, sadly, only lasted a few years until the building was destroyed by the Nazis.

Professor Willenberg, a graduate of the Fine Arts Academy, taught art and painting in the established Jewish schools, as well as in the artistic school that he founded.

He designed beautiful polychromes and stained glass windows for synagogues in Częstochowa, Piotrków Trybunalski and Opatów.

During the war, he hid in Warsaw under the name of Karol Baltazar Pękosławski. He died in 1947.

His son, Samuel Willenberg z”l, a survivor of the Treblinka death camp uprising, lived in Tel Aviv and was a noted sculptor and artist in his own right.

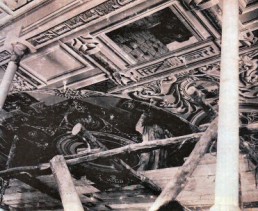

Beauty Lost Forever

Like a latter day Michaelangelo,

Professor Perec Willenberg

lovingly works on the ceiling

of the Old Synagogue.

His paintings adorned

both the ceiling and the walls

of the Old Synagogue.

An illustration by

Professor Perec Willenberg

of his design

for the interior

of the Old Synagogue.