The Graves on ul. Kawia

The Graves on ul. Kawia

by WIESŁAW PASZKOWSKI, Częstochowa Municipal Museum, History Documentation Centre

Edited: ALON GOLDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel English translation: ANDREW RAJCHER

On the night of 21st September 1942, German police (under the command of Hauptmann Schutzpolizei Paul Degenhardt, supported by armed formations) surrounded the Częstochowa ghetto and began a full isolation of the area. The deportation to the extermination camp was also accompanied by a large number of additional deaths, as the death penalty was also the result of any attempt at resistance, hiding or escape.

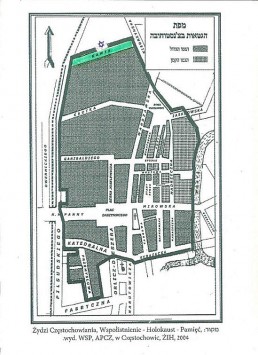

This meant that there was a need to bury those murdered within the confines of the blockade. The Germans selected vacant land at ul. Kawia 20 and 22 for this purpose, right near the northern border of the Częstochowa ghetto. According to Jewish historian Liber Brener, the author of Widersztand un umkum in czenstochower geto, before the commencement of the deportation, the Schutzpolizei had removed all the Jews from the area and, on the first day of the aktion, 22nd September 1942, the removal and burial of all the murdered corpses began.

The Germans brought (…) an older member from the Chevra Kadisha, Miśka, who was, under the supervision of the military policeman Überschär, to manage the collection of those killed and the transportation of them to ulica Kawia, where two mass-graves had already been prepared.

Hauptmann Degenhardt assured Miśka that he would be completely safe if he carried out this task well. He also allocated him an apartment on the grounds of the former “Metalurgia” foundry on ul. Krótka. Miśka was provided with carts, formerly owned by Jewish butchers and which had been used to transport animal carcasses. They were covered with timber planks which rose from the sides of the carts.

Janusz Czaryski described, in detail, the beginnings of the work carried out on that day on ul. Kawia:

At lunchtime, the Volksdeutsche Blanke (…) told us that he had been ordered to take us to “Metalurgia”. When we arrived there, that thug Degenhardt told us to run to the gate, where the Germans were already standing. He then carried out a selection, beating the Jews.

At the gate, a policeman approached me and told me to go outside. There was a group of seventy men there and the military policeman led us to ulica Kawia. Another policeman on horseback took over the group and said that we were to work. The tools were already in place.

Half of the men began digging graves, while the others stacked corpses. The military policeman said that we should carry out the work “anständig” (decently). If not, there was still room enough there for all of us.

The horror was indescribable when we saw the carts, which once transported meat, bring the dead bodies of the murdered Jewish victims. We laid the bodies into the graves in rows, head to head. After each row (layer) was laid, we poured in lime or chlorine.

We have no eye-witness description of what happened on Kawia over the following days.

Brener’s book contains a description based on post-War reports by non-Jewish residents:

The wagons, containing the dead, rolled along ulica Kawia, where the Schutzpolizei pulled gold teeth out of the corpses and cut off fingers with gold rings. These were collected into baskets and taken away. The elderly, the sick and children were also brought here. They were forced to undress and lie in a row, face down. It was only then that the military policemen went from one victim to the other, shooting each of them in the head. Later, some of the clothing was given out to residents of the street who had, earlier, been forced to throw the corpses into a mass grave.

So, the graves on ulica Kawia also became a place of murder.

Deportation trains left for the Treblinka extermination camp every three days. But, in the intervening two days, German police, assisted by auxiliary units, searched empty homes, pillaging abandoned possessions and murdering the Jews in hiding. This was why, every day, wagons brought corpses until the end of the aktion. The last transport was arranged for 7th October 1942. At that time, Degenhardt summoned Miśka and his wife and sent them to the wagons. Responding to Miśka’s complaints, he said that an officer’s word to a Jew was meaningless.

The group of wagon-drivers and gravediggers, led by Miśka, had transported 1,600 individuals to be murdered at ulica Kawia. After the War, it was reported that at least 2,000 had been murdered there. So, at least, four hundred Jews had been killed on the spot.

In Degenhardt’s post-War trial, the indictment accused him of the murder of twenty sick Jews in October 1942. They were forced labourers who were extracted, after selections, from HASAG-Pelcery. There, they had been diagnosed with some sort of disease. Due to the extremely poor sanitary conditions there (workers slept in their clothes on a concrete floor, with limited access to water and sanitation), there was a fear of an epidemic break-out. Degenhardt ordered all the sick to be brought to ulica Kawia. A pit had been dug there. Degenhardt ordered the sick to run around the grave. He took a machine-gun from a factory guard and, with one rain of bullets, he killed them all. After hearing from an expert, the court in Lüneburg considered it to be technically feasible and also found the testimony of two eye-witnesses to the murders to be credible.

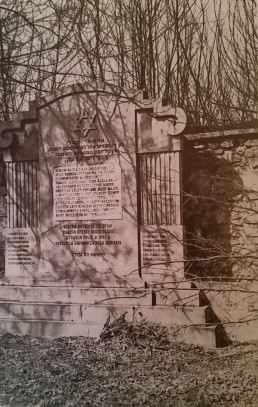

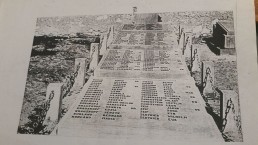

Initially, the graves were cared for by the Częstochowa District Jewish Committee. The graves were surrounded with metal mesh. There were two concrete slabs, containing inscriptions in both Polish and Yiddish:

Mass Graves of

Jews

The Victims of Nazism

22nd September 1942

May their memory be honoured.

(The right grave inscription is in both Yiddish and Polish. The left grave inscription only in Polish.)

Caring for the graves proved difficult, because the area was privately owned. The municipal authorities wanted to have the bodies exhumed, because they were afraid of an epidemic (the graves were located close to residences, next to where potatoes were being grown).

Unable to cope with its obligations, the Częstochowa District Jewish Committee handed the graves over to the Częstochowa authorities who, in turn, passed care on to the Zieleń Miejska company. After its transformation into the Municipal Public Utilities Enterprise, it continued to care for the graves. It is known that, in 1962, the graves were cleaned up. Lawns were planted over the graves and roses were planted. Concrete pavers were laid at the graves and a hedge was planted along the fence. After that, care and repair were carried out on a regular basis. For example, in 1982, the surface of the paver slabs was repaired and the fence mesh was replaced. The current cast iron surround was, most probably, installed in the 1990’s.

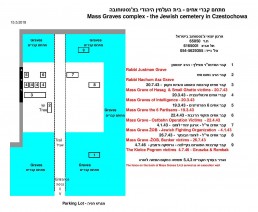

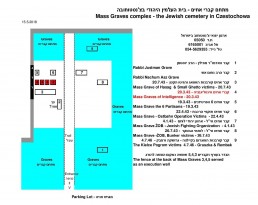

The complex consists of two graves measuring 36.0 x 4.5 = 162 sq.m. and 33.0 x 9.0 = 297 sq.m.. The whole area measures 661 sq.m.

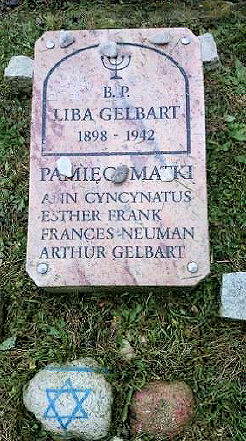

In the right-hand compound, there is another small tombstone erected by the family of a woman who, according to the testimonies, is probably was buried there. The inscription, in Polish, reads:

On blessed memory

LIBA GELBART

1898-1942

IN MEMORY OF MUM

Anne Cyncynatus

Esther Frank

Frances Neuman

Arthur Gelbart

The entrance to the left compound is alongside a building.

On the paving stones, leading to the mass grave, is an inscription created by students of the Częstochowa Fine Arts High School.

A satellite image of ul. Kawia.

The Grave of Częstochowa Victims of Kielce Pogrom

The Grave of Częstochowa Victims of the Kielce Pogrom

by ALON GOLDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel

On 4th July 1946, the day of the Kielce pogrom, Częstochowers David Yosef Gruszka and Shmuel Rembak z”l boarded the train at the railway station in Kielce with the intention of traveling to Częstochowa.

On the way, Poles recognized that both were Jews and threw them out of the train – to their deaths. When he saw that they did not make it back to Częstochowa, Abraham Gruszka, Joseph’s brother, walked along the train-tracks until he found the two bodies. He brought them home for burial in the Częstochowa Jewish cemetery.

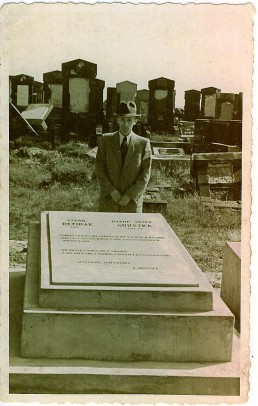

Pic left: Abraham Gruzska at his brother’s grave – Częstochowa 1946

Pic right: Abraham Gruszka and witnesses at the consecration of the matzevah

The gravestone inscription in Polish did not include Rembak’s age (25). It was later added to the cemetery inventory book by the historian Wiesław Paszkowski. The translated inscription reads:

Shmuel Rembak David Yosef Gruszka

age (25) age 38

perished tragically on 4th July 4 1946, on the Kielce-Czestochowa railway line, at the hands of fascist murderers.

Their glory be forever

An eternal disgrace to the fascist thugs.

This gravestone was laid by A. Gruszka.

Over time, either due to vandalism or to weather damage, the tombstone was destroyed. The Gidonim and historian Wiesław Paszkowski found no trace while mapping the area, although Wiesław had an of its general location.

In February 2018, during a seminar in Częstochowa, held for tour guides from Israel, we made another attempt to locate the grave and found a fragment of the stone tablet bearing a few words. (A picture of that fragment is shown below.)

The words “Kielce – Czestochowa”, in Polish, caught our attention. Abraham’s son, Aryeh Gruszka’s comparison between the fragment and the original photograph confirmed the hypothesis that this was, indeed the grave, of the two men.

Aryeh Gruszka finalised the rebuilding of the tombstone, with the original inscription, at the end of May 2018.

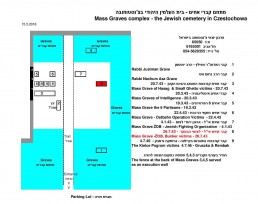

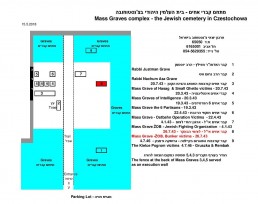

The grave is located in the plot behind the mass grave of the ŻOB victims, on a path to the right of the main path (No. 9 in the diagram below).

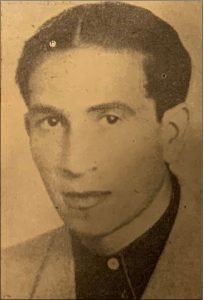

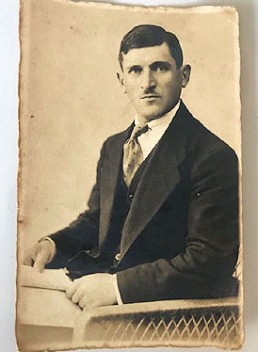

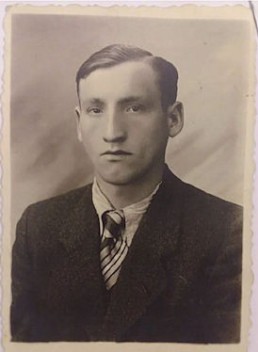

David Joseph Gruszka z”l

Shmuel Rambak z”l

Originally, a picture of Shmuel Rembak could not be found nor could his family be contacted. Also, the man with the beret seen standing at the grave in the picture on the left could not be identified.

However, after the information public amongst Częstochowa landsleit in Israel and abroad, the missing information was received. It was sent by Ya’akov Wasilewicz, a native of Częstochowa, son of Halina Wasilewicz z”l, the Director of the Częstochowa TSKŻ for 40 years, and grandson of Ya’akov Wasilewicz, who was Shmuel Rembak’s cousin. Ya’akov identified the man wearing a beret in the picture next to the grave as his father and sent a picture of Shmuel Rembak z”l.

The picture below shows Ya’akov Wasilewicz standing by the grave of his cousin, Shmuel Rembak.

On 4th July 2018, a memorial ceremony was held in front of the house at ul. Planty 7 in Kielce. Forty-six Memorial Stepping Stones were discovered in memory of the victims of the Kielce pogrom, among them stumbling blocks bearing the names of the two Czestochowa Jews – Szmul Rembak and Dawid Yosef Gruszka.

The HASAG Victims' Mass Grave

The HASAG Victims' Mass Grave

by WIESŁAW PASZKOWSKI, Częstochowa Municipal Museum, History Documentation Centre

Edited: ALON GOLDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel English translation: ANDREW RAJCHER

The inscription on this monument reads as follows:

The common monument to the hundreds of victims

of the Small Ghetto and the HAGA camp

whose lives, in 1943,

were criminally cut-short by the occupier.

May their memory by honoured.

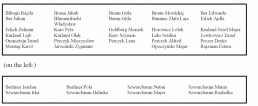

In 2016, during the monument’s reconstruction, two black plaques werr added to both sides of the tombstone. On them are recorded additional names of victims who did not appear on the original tombstone and who, according to testimony given by survivors of HASAG in Czestochowa, were sent to their deaths on 21st July 1943. Because not all the names of the victims could be identified to be memorialised, these same plaques carry this additional epitaph in English and Polish:

IN THIS VERY PLACE, ON JULY 21, 1943,

GERMANS AND UKRAINIANS SHOT

OVER 200 JEWS OF CZĘSTOCHOWA.

WITH THE PASSING OF TIME, ONLY THESE INDIVIDUALS

ARE STILL REMEMBERED.

Here are their names:

This monument was intended to commemorate the most well-known site of execution of Jews at the Jewish Cemetery. At least four hundred forced labourers from HASAG (Hugo Schneider Aktiengesellschaft, with its headquarters in Leizig) and from police warehouses were killed here. Meanwhile, only seventy-five names were placed onto the monument. The disproportion is huge. In order to understand this, it is necessary to refer to the history of the Jewish community in Częstochowa.

From the end of June 1943, following the liquidation of the forced labour camp in Częstochowa, the so-called “Small Ghetto”, all the Jewish labourers, still alive, were relocated to prefabricated camps in the HASAG-Pelcery plant and in the grounds of the steel-mill in HASAG-Raków. There was also a large group employed in the police warehouses on ul. Garibaldiego. There, they sorted, and prepared for transport to the Reich, goods that had been looted from Jews in the autumn of 1942, during the liquidation of the Częstochowa ghetto and the deportation of 40,000 individuals to the death camp in Treblinka. The mikvah (ritual bath) at ul. Garibaldiego 18 served as barracks for the last fifty Jewish policemen and their families. In July, they were transferred to HASAG-Pelcery.

On 19th July, the German meisters in HASAG-Pelcery attempted to put together a list of non-essential workers. In the face of resistance from those at risk, the attempt was unsuccessful. For this reason, under the direction of Director Lüht, engineers and meisters, in the presence of Bernard Kurland, who was the Jewish leader of the labourers group, conducted the selection at night. All the men and women were required, in ranks, to pass by the Germans. Victims were pulled out of the lines, placed into the factory compound outside the camp and then locked in the building’s basements, which served as the camp’s detention facility. After the selection, Hauptmann Degenhardt, who was in the facility and supervised the operation from a distance, ordered that Bernard Kurland be handed over and that he be added to the group locked in the basements.

On the following day, Degenhardt announced, to the labourers in the police warehouses, that anyone who wished could join their family in HASAG-Pelcery. More than one hundred individuals came forward and they were loaded onto trucks. They were transported to the basements in the facility and locked up with the others. Later, they were joined by Jewish policemen and their families. Only the wife of policeman Kohn hid, with her son, under the factory roof and thus avoided being imprisoned.

The victims were then pulled out of the basement and loaded onto vehicles. Some desperate prisoners put up strong resistance, but they were stunned with hammer blows, restrained and then thrown onto a vehicle. After being transported to the cemetery, they were all shot.

After comparing the inscription with data contained in the Central Database of Holocaust Victims at Yad Vashem, it must be stated that the victims of the selection and execution were those named in the upper table.

The remaining individuals are family members commemorated by their relatives who had survived the Holocaust. Was this only due to the difficulty in establishing the names of the victims? That would be understandable, because no Jews could have observed the execution. What is known, however, is that those, who were detained during the selection, never returned to the camp. Let us not be confused by the description robotnicy (workers/labourers). Often, the intelligencia would claim to be robotnicy in order to survive. Apart from reducing the workforce and those being fed by the Germans, a selection was aimed at finding people who lacked physical fitness or who were poor workers, those who lacked qualifications or those who pretended to be tradesmen. There, they tried to carry out selections according to work positions. So, it had nothing to do with people who were poor or who were insignificant within the Jewish community.

A large group of victims were Jewish policemen and their families. During their several years of work, especially in 1942 and 1943, they were sadly inscribed into the life of their community. There were few people who were not harmed due to them. They spied on their fellow Jews. They caught Jewish children and the elderly. They were almost all the “tested” helpers of the German police, along with their commander Herman Parasol. For the most part, they were not monsters. However, they were under constant pressure from their German superiors. Their names were well-known by many people. However, after the War, they were surrounded by disdainful silence.

The rest of the inscriptions on the monument are family memorials, most likely not related to the events of 20th July 1943.

Because the Jewish religion forbids the performing of exhumations (this can only be carried out in exceptional circumstances), it was carried out under duress. It was impossible to distinguish one from the other. Their names were omitted from the monument and what is not mentioned is that heroes are resting next to “traitors”. The Polish party authorities also spoke on this subject, ultimately forbidding the naming of Jewish policemen.

A quite typical example is that of Bernard Kurland, lying next to Herman Parasol – the most well-known of the murder victims. Although it is known that he is buried in this mass grave, his name was placed on the neighbouring grave where, amongst other members of the Jewish intelligencia, his family, who were killed 20th March 1943, are buried. Bernard Kurland avoided death at that time, escaping from the vehicle which was carrying Jews to the place of execution. It should be remembered, however, this case may also be controversial. In the grave, next to Jewish doctors, engineers, lawyers and their families, lie the last members of the Judenrat, the first commander of the Jewish Police Maurycy Galster and his son Jerzy who also served as a policeman.

In the creation of these graves-monuments, we see a strong interweaving of different motivations shown on the part of their creators. In the first instance, attempts were made to combine and to reconcile the various reasons and interests of political groups and of families. With the third monument, we are dealing with the omission of an entire group of victims, denying them the right to be remembered and natural justice when it comes to an ordinary grave. The formula in the creation of the monument created some limitations, but that formula was used inconsistently.

The monument was badly affected by the actions of time and people. Already, in the beginning (probably in the 1950’s), the central plaque was lost. The one that appears in the 1960’s differs in the layout of the text. Later, the cement joints and individual elements of the monument begin to deteriorate. Again, the central plaque is lost. In 2016, it was reconstructed during the renovation of the monument. A further plaque is added containing the names of victims, not mentioned up to that time.

Maysia Parasol

Jakub Rajcher

Jacheta Rajcher

Zysla Mariema Rozenblat

Roman (Abran Pinkus) Szładowski

Frania Frajda Szladowska

Juzio Josef Szladowski (lat 3)

Michał Szperling

Nechuma Szperling

Franciszka Szpic

Dawid Sztybel

Zygmunt Szydłowski

Pola Szyłowska

Inz. Szwarc

Dr Rachela Wajsberg

Zofia Wigdor

Fajga Beatus

Jakub Epsztajn

Genia Epsztajn

Mieciuś Epsztajn (lat 4.5)

Liliulsia Epsztajn (lat (2.5_

Jósek Fajerman

Sara Fajerman

Hana Feldman

Jerzy Galster

Moszek Gonzwa

Fela Fagla Gonzwa

Tauba Grynbaum

Jósek Jung

Szymon Kohn

Józg Kornbrot

Paulina Linka Kornbrot

Bernard Kurland

Icek Kurland

Mania Kurland

Józef Kurland

Chaja Hela Kurland

Leon Lajb Kurland

Henryk Hersz Parasol

THE ORIGINAL MONUMENT

AFTER RESTORATION IN 2016

The ŻOB Bunker Victims' Grave

The ŻOB Bunker Victims' Grave

by WIESŁAW PASZKOWSKI, Częstochowa Municipal Museum, History Documentation Centre

Edited: ALON GOLDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel English translation: ANDREW RAJCHER

The lack and, to a greater extent, the inaccuracies of journalistic information condemn us to the making of assumptions. A fundamental error in the date on the tombstone creates an additional difficulty.

The most important factor in the identification of the remains is the place in which they were found – at the exit of ul. Nadrzeczna, next to former house numbers 86, 88 and 90. From the end of October 1942, it was within the terrain of the Stare Miasto (Old Town), which was the forced labour camp for Jews, the so-called “Small Ghetto”. From that time, the Germans brought Jews here – those who still remained alive following the transportations to Treblinka and the mass murders in the Częstochowa ghetto. The camp was surrounded by concrete posts and interwoven barbed wire. It was located on the outside of the Rynek Warszawski which served as an assembly point. Entry into the “Small Ghetto” was possible through the so-called wylot (outlet). There was no gate here, just a wooden birch barricade and barbed wire, which was put in place and moved aside when necessary.

The Rynek Warszawski, a large square once used for market fairs, is now completely empty. The square was adjacent to ul. Garncarska and ul. Jaskrowska. This is where the future labour camp was to be located, with concrete poles stuck into the ground, linked with dense coils of barbed wire. Attached to them were moveable wooden trestles. When these were moved aside, a space was created through which a vehicle could be driven. The same concrete posts and barbed wire could be found along ul. Nadrzeczna.

The building at Nadrzeczna 88 was taken over by Möbellager workers. Soon, probably in the basements, they organised hiding-places into which they could smuggle the elderly, the women and the children, who could no longer be kept in the Möbellager itself. Later, this building and the one next to it were taken over by the Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ŻOB) which was formed late in 1942 (and which also contained workers from the Möbellager). ŻOB’s aim was to resist the Germans in the event of any attempt by them to liquidate the “Small Ghetto”. The issue of escape from the “Small Ghetto” was considered and, to this end, tunnels were drilled which led out of the camp. The entrance to one of the tunnels was located at the house at Nadrzeczna 88, which also served as ŻOB’s main arsenal. Because producing firearms inside the ghetto proved to be too difficult, firearms were acquired either through buying or stealing them. In the main, hand grenades were produced. These weapons were stored in the warehouse.

That the Jews were armed and ready to use them was a fact that the Germans should have realised on 4th January 1943, following the actions of Mendel Fiszlewicz and Icchak Feiner. Hauptmann Degenhardt handed oversight of the “Small Ghetto” to the Überschärr, who were slavishly obedient and brutal, but too primitive. This happened after March or even in May 1943. The first known effect of this change was the operation against Macheł Birencwajg on 8th June 1943.

The regime in the ghetto had become more severe. The newly appointed camp commandants were Schutzpolizei political affairs specialists Kestner and Laschinski, who were fluent in Polish and, thanks to that, were well-versed in the life of the ghetto. It became clear that their task was to uncover the ŻOB structure. The partisans intensified their vigilance. Assemblies of specific groups were ordered more frequently and those Jews who were connected with the two Lagerführers were watched closely.

ŻOB intercepted correspondence from Rozenberg, a Jewish policeman, to the Gestapo and, on 21st June 1943, they killed him – but it was too late. The Germans already knew the sites of the hiding-places and the tunnels. They knew a great deal about ŻOB’s activities. The organisation had used a hired truck to send arms to a group in the forest. The German driver notified the police. The vehicle was stopped by the Gestapo. In the shooting that followed, Pinek Samsonowicz was killed, Lolek Blank fled, while Harry Potasiewicz fell into the hands of the Gestapo. The Germans tortured Harry in the window of the Jewish Police building and ordered the entire populace of the ghetto to walk past it. He betrayed no one and died on the way to the place of execution.

The Germans attacked the “Small Ghetto” in the evening of 25th June 1943. They countered the vigilance of the partisans by sending in small groups of workers, which was to mimic the normal return of the day shift. When the alarm was cancelled, the partisans left their hiding-places and returned their arms to the arsenal. It was then that police cars entered the camp grounds. They first attacked the bunkers at Nadrzeczna 86 and 88, where Commandant Mojtek Zylberberg was located. Almost everyone in the hiding-places was killed. Mojtek, who was wounded, committed suicide. Now, the Germans began shooting at everyone on the streets. The liquidation of the “Small Ghetto”, the selections and the transports to be shot lasted into the following day. Many people were still in hiding in the houses, basements and attics. Some were lured out when Degenhardt announced an “amnesty”. (After three days, he ordered all those who had been “amnestied” to be shot.) However, in July, the camp was still being liquidated, with buildings being burned or blown up.

There would have been around 1,500 victims of the “Small Ghetto” liquidation. Why, then, have the remains of only a dozen or so dead been honoured? After all, the tombstone has the form of a monument. Częstochowa Jews probably thought that they were paying tribute to the bravest fighters of the “Small Ghetto”. Perhaps the body of ŻOB Commander Mojtek Zylberberg is also in this grave.

Rivka Glantz

Moitek Zilberberg

Above: Translation from Yiddish: Remnants of the bones of holy Jews, found in a bunker at ul. Nadrzeczna 82-88 , in which 200 Jews were murdered

Below: An article on finding bones on the street in August 1966

"Operation Ostbahn" Victims' Grave

"Operation Ostbahn" Victims' Grave

by WIESŁAW PASZKOWSKI, Częstochowa Municipal Museum, History Documentation Centre

Edited: ALON GOLDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel English translation: ANDREW RAJCHER

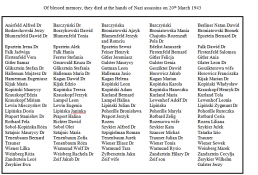

In the spring of 1943, the Jewish Fighting Organisation (ŻOB) looked for a way to fight the Germans. As a station along the transport route towards the Eastern Front, Częstochowa seemed like a good location for sabotage operating on the railway. Jewish prisoners, employed in HASAG-Pelcery, prepared keys with which to unscrew the railway track. Armed and equipped with these tools, five fighters from the “66” youth group left the “Small Ghetto” on 22nd April 1943, together with a group of Jewish workers employed on the German Ostbahn railways. They were Awiw Rozyner, Cwi Lustiger, Lolek Frankenberg (pic left), Harry Potaszewicz and Dawid Altman. They were meant to separate from the workers group and, later, rejoin them at a pre-agreed place in Błeszno.

In the spring of 1943, the Jewish Fighting Organisation (ŻOB) looked for a way to fight the Germans. As a station along the transport route towards the Eastern Front, Częstochowa seemed like a good location for sabotage operating on the railway. Jewish prisoners, employed in HASAG-Pelcery, prepared keys with which to unscrew the railway track. Armed and equipped with these tools, five fighters from the “66” youth group left the “Small Ghetto” on 22nd April 1943, together with a group of Jewish workers employed on the German Ostbahn railways. They were Awiw Rozyner, Cwi Lustiger, Lolek Frankenberg (pic left), Harry Potaszewicz and Dawid Altman. They were meant to separate from the workers group and, later, rejoin them at a pre-agreed place in Błeszno.

The first to “break off” was supposed to be Lolek. He succeeded. Dawid Altman was to be the second, but he was stopped by Bahnschutz Karna (a Volksdeutsche from Wyczerp past Częstochową). Initially, they tried to bribe Karna, but soon another German from the Bahnschutz became involved. Karna backed out of taking the bribe and both of them led Dawid to the guardhouse.

In an attempt to free him, Harry shot at the two Bahnschutz officers. One of them fell, seriously wounded and Dawid fled. Harry, Awiw and Cwi could not escape as they became surrounded by a large number of Germans who shot at them from all sides. Harry and Awiw died on the spot. Cwi barricaded himself inside a barn. He defended himself until he was seriously wounded by a grenade thrown into the barn. Alive and seriously wounded, he was captured by the Gestapo, imprisoned in their basement and tortured in order to give up the names of his companions. Cwi did not break and was shot at the Jewish Cemetery.

The Gestapo and Schutzpolizei took out their vengeance against the Jewish workers. From that group, every second worker was shot – in total, twenty five men. Amongst those shot were Jakub Mosze Gelber Litwin, Nachman Enzel, Berl Zeligman, Stefan Montag, Goldberg (from Warsaw), Rusin (a former pupil at the I.L. Perec School in Częstochowa) and Dudek Lewkowicz. This is according to Liber Brener.

After the War, a cement gravestone was made with the following inscription in Polish:

Of the twenty eight who fell, fifteen are named. In addition, we know that, in December 1942, Mietek Ferleger fell into the hands of the Gestapo. He was tortured and later shot. He is probably resting in an unmarked grave in this cemetery. He is named here so as to memorialise his name somewhere as a companion in the battle.

At the initiative of The Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel and its Chairman, Alon Goldman, the tombstone of the mass grave was restored.

On 9th June 2022, the restored tombstone was unveiled,

in the presence of the Israeli Ambassador to Poland, the Deputy Mayor of Częstochowa and a large crowd.

The Jewish Intelligentsia Mass Graves

The Jewish Intelligencia Mass Grave

by WIESŁAW PASZKOWSKI, Częstochowa Municipal Museum, History Documentation Centre

Edited: ALON GOLDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel English translation: ANDREW RAJCHER

The events which took place in Częstochowa during Purim 1943 and, on the next day, in other places in the Radomsk district, later found their counterpart in the affair concerning the Hotel Polski in Warsaw. Perhaps, initially, it was a real attempt at exchanging Jews for German prisoners held by the Allies, or for money and military supplies. In February 1943, or maybe even earlier, the Germans ordered the Częstochowa Judenrat to …

… register all Jews who had relatives in Palestine. Persistent rumours circulated that they were opening the possibility to leave (…). Almost everyone applied for registration. Whoever had no relatives there gave some a fictitious name and address. It was said that Jews would be exchanged for German citizens, who had been interned in the Middle East by the English and the French. Many thought that going to Palestine was the last resort. The credibility of the registrations was confirmed by the fact that the forms, provided by the Germans, contained many different headings including the exact name, kinship level and address of the relative. If there were many relatives, then they each had to be listed on the registration form. The Judenrat opened a real registration office run by several individuals The influx of registrants was huge. The whole affair was given the appearance of authenticity.

After two weeks, registrations were completed and all went quiet. Then it was 20th March 1943, the joyous Jewish festival of Purim.

When we left HASAG for the camp, the strange silence and peace struck me. There were no visible Schutzpolizei personnel, who usually stood at the gate and carried out random personal searches. The streets of the camp were deserted.

Unexpectedly, at 5:00 pm, the commander of the Schutzpolizei, Hauptmann Paul Degenhardt, appeared at the Judenrat office. He said that he would dictate the list of names of the first group to be going to Palestine. It would contain those who deserved it by means of their conduct. Degenhardt ordered the Jewish police to call all these individuals for registration. They were then led to the Rynek Warszawski, which adjoined the fence of the “Small Ghetto” and which served as an assembly point and a gathering place. The individuals summoned were those who held academic qualifications – doctors, lawyers and engineers, as well as members of the Judenrat and their families.

Degenhardt counted those assembled at the Rynek and, after confirming that there were more than one hundred and forty individuals, he called over the military police and ordered them to lock everyone into the nearby German guard-post. Shortly after, trucks arrived and the Jewish intelligencia were forcibly led out and, again with force, loaded onto the trucks.

According to a different version of events:

At some point, armed Germans from the Schutzpolizei emerged from the gate on ulica Warszawska. They surrounded the Jews assembled on the Rynek and rushed them towards the trucks, covered with tarpaulins, which were standing in the street. It was only then that the victims of this German hypocracy understood the terrible truth – but it was too late to back out. The butts of rifles came crushing down on them, beaten as they protested. Judenrat member, Zelig Rotbard, who persuaded his young daughter Fela to go with him to the Rynek, now pleaded with the German officers to, at least, let her go.

The cars moved along ulica Warszawska, turned into Mirowska and then into Olsztyńska – namely the route leading to the Jewish Cemetery, already known to Częstochowa Jews as a place of execution. It was then that Maurycy Kopiński, brother of the Judenrat chairman, told his nephew Władek Kopiński, sitting next to him, to escape. He also jumped out of the speeding truck. According to another version of the escape, it was Bernard Kurland who instigated it. The dentist, Dr Anna Bresler, also jumped off, which caused her to break a leg. But she managed to reach the home of one of her patients, who hid her. A dozen or so individuals escaped. Shots were fired at those escaping, but the trucks only stopped when they had reached the cemetery, near the shtiebel. There, all the victims were gathered and told to strip naked. They were then led in pairs to the already prepared grave where they were shot dead. In total, 127 individuals perished in this tragedy. Almost the entire list of people is named on the tombstone’s inscription.

This plaque was the first to be destroyed. Then the quadruple tombstone became eroded, especially its two northern parts. However, in the first years of this century, the list of victims was still legible. However, due to the thoughtless restoration work by a private individual, the cracked pieces of concrete were removed and replaced with a new smooth, cement surface, without any inscriptions.

UPDATE: On Wednesday, 15th June 2023, a ceremony was held at the Częstochowa Jewish Cemetery to consecrate the restored three mass graves of the Jewish Intelligentsia.

Through the efforts of World Society Vice-President, Alon Goldman, and others, the Polish government recognised these burial sites as official “War Graves” and, therefore, they qualified for government funding to have them restored.

Following the completion of the restoration work, the ceremony was held to consecrate these sacred sites.

The Jewish Fighting Organisation (ŻOB) Monument

The Jewish Fighting Organisation (ŻOB) Monument

by WIESŁAW PASZKOWSKI, Częstochowa Municipal Museum, History Documentation Centre

Edited: ALON GOLDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel English translation: ANDREW RAJCHER

This monument is also a war grave. It is located in Complex I of the cemetery, on the right-hand side of the main pathway, approximately two-thirds along its length. It is in the form of an aedicula (a composition consisting of two pillars, columns or pilasters which support the entablature with a pediment or outpost), a style often found in this cemetery.

It consists, however, of heavy, concrete blocks. Its entirety is set on a low pedestal. The central section consists of a massive plaque, with protrusions which make the centre recessed. The panel is made into a central inscription plate, with highlighted colour and made of black granite. On both sides, there are bas-reliefs of stylised menorahs containing burning candles. Two pairs of low columns are placed above the protrusions, between them is a horizontal plaque containing the main monument inscription. The peak is in the form of a flattened prism set on a massive horizontal beam. A Star of David sits above it all. Two lower panels, containing inscriptions, have been added to both sides of the aediculus. In front of the monument is an open frame outlining the area of the grave. The frame contains posts, originally finished with stylised burning torches. Metal chains have been hung between the posts.

The current form is the result of a renovation carried out by the City Council in 2012, during which the central plaque was lost. Monument elements were reconstructed and grey granite inscription tablets were created using the pattern of the original and containing inscriptions which had faded from that original.

The main inscription on the monument, in Yiddish and in Polish, expresses the intentions of the authors:

Glory to those heroes who died

in the armed struggle with the occupiers

04/01/1943

Only surnames with first names follow:

| Zylberberg Mojtek | Glanc Rywka | Fajner Icchok | Fiszlewicz Mendel | Fiszlewicz Mendel |

| Abramowicz Sumek | Potaszewicz Harry | Pejsak Heniek | Tencer Heniek | Szczekacz Pola |

| Szczekacz Dosia | Rozenberg Mojsze | Frajman Hersz | Frajman Rywka | Blechsztajn Ojzer |

| Bram Bela | Blank Lolek | Berkensztadt Mojsze | Berkensztadt Rajzełe | Eksztejn |

| Fajgenblat Mojsze | Gliksztajn Jehuda | Gliksztajn Lutek | Goldberg | Najman Hipek |

| Hirsz Pola | Haftka | Jakubowicz Szymsia | Kopiński Władek | Kantor Josek |

| Kapłan Abram | Mass Jadzia | Rypsztajn Kuba | Rozencwajg Marysia | Rząsiński Izydor |

| Rodał Mojsze | Radoszycki | Samsonowicz Pinek | Szuldman Wigdor | Szymanowicz Izrael |

| Szydłowski Lejzor | Sielcer Dawid | Sztull | Szajn Joachim | Szajn Perła |

| Tuchmajer Mojsze | Trembacki | dr Wolberg Adam | Windman Icchak | Wojdzisławska Lunia |

| Wajskopf Michał | Wajntraub Mietek | Wiernik | Wigodzki | Żarnowiecki Zukon |

| Zylberszac Mojsze | Zborowska Bela | Zajde Abram | Lubling Mojsze | Rozyne Jakub |

| Rozyne Estera | Asz Mendel | Birencwajg Machel | Birencwajg Adasa | Blumenkranc Fiszel |

| Rozensztejn Natan | Lewensztajn Mojsze | Kałka Berek | Kałka Józef | Lichter Kopel |

| Brzuska Zelig | Brzuska Lipman | Brzuska Mordchaj | Kusznir Chaim | Wilinger Mendel |

| Tenebaum Lejb | Brener Chana | Brener Chaim | Brener Machcia | Brener Nelli |

| Berliner Basia | Berliner Icchak Hersz | Berliner Natan | Doński Lejb | Dońska Liba |

| Dońska Dwojra | Dońska Saba | Fiszel Abram kantor | Frank Lejbuś | Frank Hela |

| Frank Oleś | Gewercman Dow | Goldminc Abram Icek | Goldminc Cypra | Goldminc Natan |

| Goldminc Genia | Goldminc Lolek | Horończyk Idesa | Horończyk Henoch | Krauze Grojnen |

| Krauze Telca | Krauze Wolf Aron | Krauze Chana | Krauze Dana | Krauze Jakub |

| Wajchman Kuba | Krakauer Szmul | Krakauer Iśka | Krakauer Różka | Krakauer Gitla |

| Krakauer Zyskind | Krakauer Frandla | Krakauer Wolf Aron | Krakauer Abram Józef | Krakauer Josek |

| Krakauer Sala | Koniecpolski Eli | Koniecpolska Gitla | Niemirowski Szmul | Wajchman Bala |

| Wachtel Henryk |

The key to reading the monument is a description of the historical event which it commemorates.

On 4th January 1943, early in the morning (around 5:00 am), Hauptmann Paul Degenhardt’s deputy, Lieutenant Rohn, arrived at the Rynek Warszawski (today known as “Plac Bochaterów Getta”). At his orders, all the groups of people emerging from the “Small Ghetto” were tightly guarded in order to prevent those, who were unemployed, avoiding being sent to the labour camp and then hiding from the German police. Later, all was calm, however the residents noticed that the whole area was surrounded by police and that they were being watched attentively.

At 10:00 am, Rohn told all the people living in the “Small Ghetto” to enter the Rynek Warszawski, these included all those working in the Judenrat and its office, kitchen and workshops. This operation was clearly aimed at those employed within the Judenrat office apparatus, as well as those who had evaded work (for ideological reasons, some of the youth in the Jewish Fighting Organisation (ŻOB) did not want to work for the Germans). During the course of the selection conducted by Lieutenants Rohn and Sapparta, groups of several hundred physically weak and elderly people were placed under arrest in the German guard-post. Also taken into custody was a whole group of young people who had originally been barracked in a house at ulica Nadrzeczna 66, forming a branch of ŻOB (known as the “66” from the address). This was the “penalty” for coming late to the selection.

Later, Jewish policemen were ordered to search for hidden children. Because, at first, they did not find anyone, Rohn gathered them together and declared that each of them had to find at least two children and was responsible for carrying out the order at the risk of their own head. Now, the police began to act with total ruthlessness, breaking into apartments, pulling children out from under beds, from basements and from attics.

The children were loaded onto carts which had been used for waste disposal and sent to the Polish police station at ul. Piłsudskiego 21. Then it was the turn of those under arrest. The Germans did not expect any difficulties. However, the “66” group, led by Mendel Fiszlewicz (an escapee from the camp in Treblinka), decided that they would not allow themselves to be passively placed onto a transport. The sound of shots was to be the signal for escape. Fiszlewicz and his friend Izaak Feiner put up armed resistance. Fiszlewicz shot at Rohn, wounding him. But the pistol jammed and so he could not fire again. Feiner only had a knife which he used to slightly wound Sapparta. Stunned for a moment, the German police fired at the rebels, killing Fiszlewicz and fatally wounding Feiner. Only two girls managed to take advantage of the confusion. They were from another youth group – “Kibbutz”. Unnoticed, they joined those who had not been selected.

All the Jews in the Square were forced to raise their hands and to step back behind barbed wire. Out of the group standing nearest to the incident, the police selected every tenth person – twenty six individuals. Each of them was sentenced to death. Among them was the Commander of the Jewish Police and Judenrat member, Maurycy Galster. Until then, people prominent in the ghetto had avoided any repressions. Greatly concerned, the Chairman of the Judenrat, Leon Kopiński, succeeded in having Galster freed. The remainder were escorted past the fence and were shot against the wall of the nearest building.

The several hundred Jews in the Warszawski Rynek were surrounded by German police and led to the police station on Piłsudskiego. The Germans continued to search the camp grounds. One of them noticed two women, a mother and daughter, who were coming out of their apartment and were trying to cross over to the “Aryan side”. They were carrying money and valuables. He shot at them, but missed. However, one of them stopped. He ordered them to hand over all that they had and then told them to go. As they left, he shot, killing both of them on the spot.

It was now that groups were returning to the camp from their workplaces. Many could not find their family members – those who had been shot or who had been led away to the police station. They saw the twenty seven bodies lying in the street. Among them, they recognised friends and family members. It was already after dark when the bodies of the twenty seven men were buried in two mass graves, next to the bodies of the mother and daughter. For a long time, people stood by the graves. They only dispersed when ordered to do so.

On the following day, Judenrat Chairman Leon Kopiński tried to have freed those who had been imprisoned on ul. Piłsudskiego. He claimed that some of them were vital to the work which the Judenrat had been ordered to carry out. Lieutenant Rohn declared that they would be released if the Jewish Police would provide the same number of children and adults of lesser “value”. The Jewish Police again began the hunt for hidden children. The exchange took place on the square of the police station. Later, two hundred children and several hundred adults were transported to Radomsko. From there, together with other Jews from that town, they were transported to the extermination camp at Treblinka.

In January 1946, the Częstochowa Jewish Committee (chaired, at the time, by Liber Brener) organised the exhumation of the bodies of those executed on 4th January 1943. The local Jewish community took part in the event. The exhumed bodies were moved to the Jewish Cemetery and buried in a common grave. On one of the photographs, one can see a temporary wooden plaque, bearing inscriptions in Polish and Yiddish, which was placed onto the grave:

In honour of those, of blessed memory, victims of Nazi bestiality who died in the Częstochowa ghetto on 4th January 1943.

| Fajner Izak | Amsterdam | Fiszlewicz | Iszajewicz Dow | Haftka Jojne |

| Hammer | Wiernik | Wajdenbaum Moszek | Wygodzki Szmul | Zilberszac Abram |

| Trębacki Lejzor (?) | Eksztajn | Frajman Hersz | Potaszewicz | Rodał Moszek |

| Rozensztajn Natan | Rychter Jakób | Szelcer Dawid | Sztal Boruch | Goldberg Gedalia |

Twenty men are named on it.

It was only three years later, when the temporary plaque no longer existed or was already illegible. Then a monument with a completely different inscription was placed there.

The difference in the sound of the Yiddish and Polish inscriptions is distinctive. The first is precisely: Eternal glory to the heroes who fell during the first armed attack against the German executioners. It can be seen that the monument has been dedicated not to the victims, but to the heroes. The group of those honoured had been broadened. To the names of those killed in the incident on 4th January 1943, which had been reviewed (which is evidenced by significant differences such as spelling mistakes and the omission of names of individuals), have been added the names of many others.

Thirteen names had been engraved on the central plaque, which is distinguished by its colour (probably made of black granite): ŻOB Commander “Mojtka” Zylberberg, Rywka Glanc, Feiner and Fiszlewicz, four partisans known from other armed operations, the young Szczekacz sisters who had formed the “66” group, not mentioned in the accounts and memoirs of Mojsze Rozenberg and the Frajman couple. Hersz Frajman was one of the execution victims and, from 1905, was also a known Bund activist. His wife, Rywka, was also a respected Bund activist and instructor. In 1906, she had been seriously injured. On 4th January 1943, on hearing the news of her husband’s death, she had a mental breakdown. She took up her grandchild and volunteered to go on the transport, knowing that this would mean death. That order of events determined a certain hierarchy and became almost symbolic. At the same time, such a set of names contradicted the inscription – especially in the Polish wording.

In other places on the monument, the names of the “66” group are mentioned abundantly. When the ghetto was liquidated, many people were included, but the core was formed by:

Izio Feiner, Mietek Ferleger, Mendel Fiszlewicz, Lolek Frankenberg, Harry Gerszonowicz, Rysia Gutgeld, Lusia Gutgold, Sara Gutgold, Hipek Heiman, Pola Hirsz, Jadzia Mass, Awiw Rozyner, Marysia Rozencwajg, Saba Rypsztajn, Kuba Rypsztajn, Maniek Rozencwajg, Dosia Szczekacz, Pola Szczekacz, Mietek Wajntraub, Lunia Wojdzisławska, Icek Windman, Zborowska, Samsonowicz, Wojdzisławski, Frankenberg and Benclowicz.

Who were the other heroes of the monument? Among them was Machel Michał Birencwajg, who is named along with his wife Hanka Hadasa. During his school days, Michał was active in the Zionist movement, but he later moved to a communist organisation. During the occupation, he was employed as an upholsterer and soon became the Jewish director of the furniture plant, namely, the Moebellager. During the mass deportations of September and October 1942, he saved hundreds of lives, helping escapees from blockaded streets and hiding people in the Moebellager. He would later smuggle them into the “Small Ghetto”. He formed the underground movement quite early, during the period of selections and blockades, during the most horrible terror. He enjoyed a position of the greatest authority amongst his companions. On 8th June 1943, Michał avoided being caught by the police. However, on that day, his mother died. His wife was detained and, two days later, was shot. Michał had “Aryan papers”, but he did not try to save himself by fleeing from Częstochowa. Robbed by the Poles who were hiding him, he was handed over to the Germans, who killed him at the Jewish Cemetery on 28th July 1943, along with a group of sixty Jews.

Dr Adam Wolberg is also named on the monument. He was a dermatologist and a professional officer, a captain in the Częstochowa Regiment. He fought in 1939 and became a prisoner-of-war. After returning from imprisonment, he worked as a doctor for the Society for the Protection of the Jewish Population (TOZ). He was one of the organisers and directors of the activities of the underground. In particular, he fought fiercely with the Judenrat. He favoured armed resistance against the Germans and, at the end of 1942, in discussions with various Jewish parties and organisations, he represented the Bund. He was nominated by the Bund as the military commander. In unknown circumstances, the leadership of ŻOB was taken over by a young group of Zionist activists. However, they lacked preparation for any armed underground activity. Adam Wolberg was exposed. He was caught in a German round-up and, on 19th March 1943, he was shot. He deserved a more prominent place on the monument. However, in 1949, it was not possible to include him due to his Polish Army.

Mojsze Lubling was one of the most active members of the Arbeter Rat collective, which actively defended the interests of Jewish forced labourers in 1941 and 1942. He was transported to Treblinka and worked there as a commando member. He was one of the organisers and leaders of the uprising, in which he perished, in August 1943. He was not present in Częstochowa in January 1943, but he was already considered among its heroes. That paved the way for him to be included on the monument.

A surprise is the inclusion, on the monument, of Cantor Abram Fiszel of the New Synagogue. He was born in 1885 in Sosnowiec. He was a singing teacher and cantor and, according to the reports of various people, he perished on 22nd September 1942 on the streets of Częstochowa, as one of the first victims of deportation. His body was probably buried in the grave on ul. Kawia. His wife and three daughters perished in Treblinka. Only one daughter survived – Laja Danziger, who was in Łódż under “Aryan papers”.

Noteworthy is the omission of the two women killed on the same day (only one author mentions them – Szlomo Waga), even though the exhumation of the graves should have revealed them lying side by side.

Families named on the monument are Brener, Doński, Frank, Goldminc, Krauz and Krakauer. The first of these named families is a typical example. Chana, Chaim and Machcze Brener are the mother, brother and sister-in-law of the chairman of the Częstochowa Jewish Committee. They came from the small town of Turzysk in Wołyn. The son, Liber, took in his widowed mother probably before the War. In 1942, Chana was deported to Treblinka and was murdered there. The brother and his wife continued to live in Turzysk and perished there in 1942. Named along with them is Nelli, probably their daughter

As can be seen, this monument became a place of remembrance of various people and events. It was formally dedicated to the participants and heroes of the first attempt at armed resistance on 4th January 1943 – two weeks before that which occurred in the Warsaw Ghetto, where the Germans were attacked on 18th January 1943. Częstochowa residents claimed this as an historial “first”. Because the participants were members of the ŻOB fighting group, the entire group was commemorated on this monument, including the names of its leaders and many of its members. The founders and managers of the Arbeter Rat are also named, as are later prisoners in Treblinka and participants in the uprising there.

It is not limited to naming members of Jewish families just from Częstochowa. Others have been included who perished at various times and in various places.

The Partisans' Grave

The Partisans' Grave

by WIESŁAW PASZKOWSKI, Częstochowa Municipal Museum, History Documentation Centre

Edited: ALON GOLDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel English translation: ANDREW RAJCHER

The image of the grave many years ago – today part is difficult to read.

Within the Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (Jewish Fighting Organisation), there were two suggestions for action. Some fighters favoured defending the “Small Ghetto” in the event of any attempt by the Germans to liquidate it. Others wanted to leave the “Small Ghetto” and conduct a guerrilla fight against the Germans from the forests of Olsztyn and Złoty Potok.

At the beginning of March, five fighters were sent to the forests – Moniek Flamenbaum, Olek Herszberg, Janek Krauze and Heniek Richter (the son of pre-War communist activist Dawid Richter) and Jerzyk Rozenblat. Szlamek Szajn joined the group later. He had long been sought after by the Gestapo.

Initially, they maintained contact with the (communist) Gwardia Ludowa (People’s Guard). Later, their situation became dangerous when they were attacked by a reactionary group of the Armia Krajowa (Home Army). They returned from the forest and barricaded themselves in a bunker of the building at Wilsona 34, where there were stores of old, broken, Jewish furniture. These warehouses belonged to the Möbellager. It was from there, from time to time, that they arranged their “excursions”.

That same building also contained bunkers in which were hidden several Jewish families, including the elderly and children. Among those who were there was the wife of Dawid Kongrecki, together with their two children. Due to the carelessness of the older Kongrecki child, on 17th March 1943, the Gestapo discovered the bunker containing the six young partisans. They were suddenly attacked, leaving them with no time to use their weapons.

Felicja Karay tells the story a little differently:

The Kongrecki family, the mother and her two sons, were hiding in the same building. When, one day, one of the boys went outside, he was caught by a German who beat him until he revealed the hiding-place of the partisans. Surprised by the police, they had no time to use their weapons. It is also possible that they decided not to use them, so as not to reveal the location of the bunkers where the children were hidden. They were thrown into the Gestapo prison. There, they met another Jewish boy who, later, was released and told his parents about the partisans’ last moments. They did not give their real names so as not to endanger their families. On 19th March, after two days of merciless torture, they were taken to the Cemetery and shot.

After the War, the families of those murdered arranged for a cement grave, typical for those years, with the inscription, in Polish:

Here rest six young Jewish partisans who fell fighting for freedom on 19th March 1943

Flamenbaum Moniek age 21

Herszenberg Olek age 26

Krauze Janek age 23

Rychter Heniek age 19

Rozenblatt Jerzyk age 18

Szajn Szlamek age 23

May their memory be honoured.

There is also a second block with the same inscription written in Yiddish.

Over time, the grave has deteriorated (just as have others similarly constructed) or have fallen victim to vandalism. Unfortunately, from 1970, the Cemetery became inaccessible (It found itself within the grounds of a securely guarded industrial plant.) and, after 1989, it lacked any supervision. For this reason, at the end of the 1990’s, Sigmund Rolat decided to move the remains of his brother and his companions to another, more suitable, place. During the exhumation, it turned out that the grave was the resting place of at least seven individuals. Because it was then thought that a mistake had been made and that they were disturbing the wrong grave, the work’s administrator decided to return the remains into the ground. It was only later that he discovered that the truck, which had left the Częstochowa prison with the six partisans, had been stopped along the way by a military policeman who threw in the body of the young Kongrecki boy.

The cement monument was then remade, recreating its original form.

A temporary memorial plaque placed on the partisan grave after the war, until the permanent gravestone was erected.

A temporary memorial plaque placed on the partisan grave after the war, until the permanent gravestone was erected.

The grave of the six partisans is the solitary grave by the wall. The other four graves in the column are the graves of Czestochowa Jewish intelligentsia.

The grave of the six partisans is the solitary grave by the wall. The other four graves in the column are the graves of Czestochowa Jewish intelligentsia.

Sigmund Rolat next to the grave of his brother Jerzy – today the face of the gravestone is partly difficult to read.

Sigmund Rolat next to the grave of his brother Jerzy – today the face of the gravestone is partly difficult to read.

FOUR OF THE SIX PARTISANS

(If anyone has photographs of the other two partisans, Alon Goldman would be pleased to received copies of them.)

SZLAMEK SZAJN

Photo courtesy of the family

Photo courtesy of the family

MOSHE-MONIEK FLAMENBAUM (“Władek”)

Photo: Ghetto Fighters’ Archive

Photo: Ghetto Fighters’ Archive

JANEK KRAUZE

JERZY ROZENBLATT

Czestochowa 1946 – a memorial ceremony for the six partisans

Czestochowa 1946 – a memorial ceremony for the six partisans

The Jewish Cemetery's History

The Częstochowa Jewish Cemetery's History

by WIESŁAW PASZKOWSKI, Częstochowa Municipal Museum, History Documentation Centre

and ALON GOLDMAN, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel

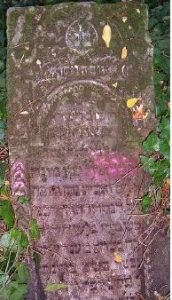

The Czestochowa Jewish cemetery was established in 1808 outside the city limits, on the right bank of the Warta River, near the village of Kucelin. Prior to this, the Jews of Czestochowa had been buried in Janów.

It is the third largest Jewish cemeteries in Poland, mostly covered with forest and thick vegetation. It has an area of 9.5 dunams with around 4,500 tombstones from the 19th and 20th centuries having been preserved. The earliest tombstone that has been found dates back to the beginning of 19th century, 1810, that of Moshe David Ben Menachem Mendel (Hermanowicz) z”l. The last burial took place here in 1973.

It is the third largest Jewish cemeteries in Poland, mostly covered with forest and thick vegetation. It has an area of 9.5 dunams with around 4,500 tombstones from the 19th and 20th centuries having been preserved. The earliest tombstone that has been found dates back to the beginning of 19th century, 1810, that of Moshe David Ben Menachem Mendel (Hermanowicz) z”l. The last burial took place here in 1973.

Most of the tombstones were made of sandstone and limestone. Some of them have colors: red, black, yellow and gold. They have Hebrew and Polish inscriptions.

Most of the tombstones were made of sandstone and limestone. Some of them have colors: red, black, yellow and gold. They have Hebrew and Polish inscriptions.

The Rebbe of Piltz, Pinchas Menahem Eliezer Justman, who died in 1920, is buried in this cemetery. Each year, many Hasidim from all over the world come to his grave and the son of the righteous Yitzchak Meir Justman is also buried in this ohel. Signs on trees – “השפתי צדיק” – point the way to his ohel.

The area of the cemetery was enclosed by a brick wall. The boundaries of the cemetery are preserved, despite the fact that the wall surrounding the cemetery is mostly destroyed. The entrance to the cemetery is marked on both sides of the road.

The area of the cemetery was enclosed by a brick wall. The boundaries of the cemetery are preserved, despite the fact that the wall surrounding the cemetery is mostly destroyed. The entrance to the cemetery is marked on both sides of the road.

Users of Waze or GPS should be directed to the following street: ul. Odlewnikow. When reaching the sign to the cemetery, turn in the direction of the sign, under the water pipe to the the dirt road, ul. Złota, until you reach the parking lot in front of the cemetery.

During World War II, the cemetery was partially destroyed. Some of the gravestones were uprooted by the Germans and used for construction purposes. In the cemetery, the Germans carried out many executions of Jews from the local Ghetto and from the HASAG Forced Labor Camp. Men, women, and children, deemed unfit for work, were executed there. The bodies of Jews of those who were murdered in the city, during the War, were buried throughout the city. When the War ended, their bodies were transferred to a permanent grave in the cemetery.

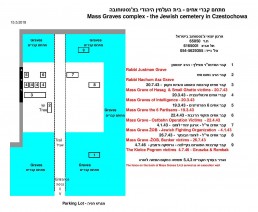

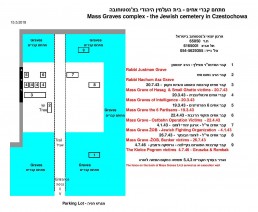

The road into the cemetery leads to a square in the centre of the cemetery. It is here. you can find the grave of Rabbi Nachum Asz, who was the Chief Rabbi of Częstochowa and seven mass-graves and monuments. On the way, to the right, you pass the ohel of the Rebbe of Piltz.

At the end of WWII, the local populace stole the most precious gravestones from the cemetery. In 1950, the Polish authorities decided to include the cemetery within the area of the metal factory Huta Częstochowa. From that moment, access to the cemetery was difficult and limited. Despite the initial fears about the preservation of the cemetery, it turned out that the decision to limit access saved the Częstochowa Jewish Cemetery from further destruction. However, the ravages of time have taken their toll and the cemetery has been subjected to progressive deterioration. Most of the wall around the cemetery, about 1 km long, has been damaged, vegetation has spread and has covered the graves. Many trees have grown in the area and, later, bad weather conditions have caused these trees to collapse.

In 1984, with the assistance of the Nissenbaum Family Foundation, the wall in front of the cemetery and the entrance gate were renovated. In 1986, the cemetery was placed on the list of sites for preservation by the Polish government. The Chevra Kadisha lists were lost and or destroyed during the WWII.

In 1986, the Jewish cemetery in Częstochowa was declared a national heritage site.

Poles carried out the first mapping of the cemetery in 1970.

Between the years 2008 AND 2016, a mapping project was conducted by Reut High School students from Jerusalem, led by the educator Ms. Dina Wiener, in cooperation with the Association of Czestochowa Jews in Israel. Its its results were published on the website http://www.gidonim.com/.

The last official burial in the cemetery was that of Albert David z”l which took place on 3rd May 1970. Up until 1973, there were also some “illegal” burials .

On the basis of the first mapping made by Poles in 1970, for many years, historian Wiesław Paszkowski of the Czestochowa Museum Documentation Centre studied the history of the cemetery and its graves. His work included, in some cases, an expansion of the information about the deceased, their family and their descendants. He used information which he found in the Częstochowa National Archives and other various sources. In 2012, he published the first volume of the Polish guide to the Jewish Cemetery of Częstochowa.

In 2018, Alon Goldman integrated the data from the mapping conducted by the historian Wiesław Paszkowski with the mapping created by the Gidonim and the results of the work were uploaded to the Gidonim website which can be searched in IN HEBREW or IN ENGLISH. Anyone who needs help in searching for graves of their relatives is welcome to contact Alon Goldman by email czestochowajewsinisrael@gmail.com.

Unfortunately, over time, the general condition of the cemetery has declined. Since the end of the WWII, the Jewish community of Częstochowa (Częstochowa Żydowska Gmina), which offially no longer exists, has been registered as owner of the cemetery. Currently, the local Jewish community of Katowice, which is in charge of the Częstochowa region, and the Częstochowa municipality are not willing to take responsibility for the cemetery.

In preparation for the World Reunion of Częstochowa Jews in October 2012, the Mayor of Częstochowa, Krzysztof Matyaszczyk and the Częstochowa City Council, restored the cemetery gate and renewed the Central Memorial, (No 7 in the chart).

In anticipation of the World Reunion of Częstochowa Jews, which took place in September 2016, Sigmund Rolat renewed the mass grave of victims of the Small Ghetto and Hasag (No 3 in the chart). This innovation included the addition of marble slabs with names of victims that were not on the original tombstone.

In June 2018, after many years of neglect, at the initiative of Alon Goldman, Chairman of the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel and the Vice-President of the World Society of Częstochowa Jews and Their Descendants, initiated a project to clean up the cemetery. The following organisation participate in the project:

o The US Matzevah Foundation led by Rev. Steven D. Reece (http://www.matzevah.org/).

o The Fundacja ADULLAM of Częstochowa, an association of Christians living in the area where the Jewish ghetto was located, led by the principal, Mrs Elżbieta Ferenc.

o High school students from the various schools in Częstochowa and volunteers.

The cleaning project continues.

As of 2018, some high schools who come from Israel to visit Częstochowa, as part of their visit to the cemetery, perform various cleaning tasks on a voluntary basis.

Below is a video about the Jewish Cemetery of Częstochowa.