Machel Birencwajg

Machel Birencwajg

- craftsman, head of the Möbellager and a leader of the Jewish underground

Machel Michał Birencwajg was born on 10th July 1907 in Częstochowa, the son of Icek Majer and Bajla née Kurnendz. He was a craftsman, communist and leader of the Jewish underground.

Machel Michał Birencwajg was born on 10th July 1907 in Częstochowa, the son of Icek Majer and Bajla née Kurnendz. He was a craftsman, communist and leader of the Jewish underground.

He received a traditional Jewish education in a cheder, after which he studied at the Jewish Gimnazjum. There, he joined the Zionist circle and was also a member of the Ha’Shomer Ha’Tzair scouting movement, as did his elder brother Pinchas and sister Mania (Ruchla). Machel was a charismatic, daring young man, full of energy and an accomplished skier. Very soon, he came to doubt the Zionist ideal and joined the illegal Communist Party

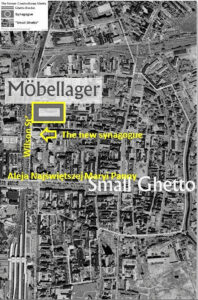

One of the most important forced labor camps in Częstochowa, during the German occupation of WW II, was the Möbellager (furniture warehouse) (ML) located at ul. Wilsona 20-22. It was on the outer edge of the ghetto, while the other side faced the “Aryan” part of the city. The grounds, spreading over two large yards, with storage facilities, belonged to Lewkowicz before the war, and Wajsberg also had his factory there. The Möbellager grounds were under the jurisdiction of the City of Częstochowa and Mayor Linderman assigned its supervision to Paul Lange.

Lange was a soft-spoken man and, amongst the few children in the Möbellager, they referred to him, “Those wearing a brown uniform they are nice guys, but those in a black uniform, oh boy, they are mean. He was nicknamed “Chazn”.

After the mass deportations to Treblinka, starting 22nd September 1942, almost all children his age had disappeared from the streets of Częstochowa. For this age group, the city had become  essentially “Judenrein”.

essentially “Judenrein”.

There was a rumor in the Möbellager that Lange, certainly, knew all the time about the “bunkers”, where mothers with their children were hiding, but probably for his own security he withheld his secret.

Lange would spend his days bored in his office. When he learned about Machel Birencwaig’s popularity among his fellow workers, he entrusted him with the management of the Möbellager. In essence, Machel became the Möbellager’s CEO much to the relief of Lange who, from time to time, could leave the city on a bird hunting spree.

Machel’s popularity reached outside the bounds of the Möbellager – people in the ghetto nicknamed the Möbellager the “Machel Lager”.

Lange’s decision, to hand over full powers to Machel, was a gift of Providence, as it gave Machel and his colleagues the opportunity to save many lives from the hands of the murderers. During the deportation of the Jewish population from the ghetto (in September and October 1942), Birencwajg and his companions saved hundreds of Jews and hid them in the Möbellager.

Following the opening of the “Small Ghetto”, they were smuggled there, despite the presence of Germans and two Jewish spies (“Kulibajki” and Gnata), who were specifically sent by the Gestapo. These activities were made possible due to Birencwajg’s determination and mental resilience. (Mothers, with their children, were transported inside wardrobes, sofas, and chests, and were hidden in shelters prepared by the underground.)

Workshops were built in the Möbellager, which employed professional Jewish tradesmen in many areas of competence – carpenters, locksmiths, electricians, sanitary specialists, automobile mechanics, painters, upholsterers, curtain decorators, etc.

When Machel took over, sixty craftsmen worked there but, following the 22nd September to 4th October 1942 deportations, when 40,000 people were sent to the Treblinka death camp, he negotiated with Mayor Linderman for more help, and their numbers soon doubled. They then called in the rest of their families from the ghetto, and the number grew to around 400.

After the deportations, teams of workers were sent out from the Möbellager to the ghetto, which had turned into a ghost town, to collect furniture and valuables from the now empty homes. This mission was assigned to Machel Birencwajg.

Carl Langner writes:

“One day, Machel learned that there was still a family hiding at Aleja 10. He sent a group, comprising his brother Pinchas and his cousin Jankev (Mojs) Rajch, to get them. They took a horse-driven platform charged with furniture and machines, found the family and smuggled them. The children were hidden in sacks surrounded with machines. On the way back to the Möbellager, they had to pass through German and Ukrainian control stations. One of them was corrupt, but another was not. They all risked immediate death if anything was uncovered.“

However, perhaps the most spectacular rescue occurred on that fateful Yom Kippur on 22nd September 1942, when the first “Akcja” took place, and a few thousand of the “selected” were sent to the Treblinka death camp. The route to the Umschlagplatz, the train station near the Warta River, led along ul Wilsona. As the crowd was passing the Möbellager, Machel and a group of workers, in a daring and heroic move, taking advantage of the turmoil, somehow distracted the Schutzpolitzei guards away from the gate. When the terrorised and panicked crowd of elderly people and mothers with their children came near, many rushed inside the open gate. Up to six hundred people were saved that day.

When the “Small Ghetto” was opened in November 1942, Hauptman Paul Dagenhardt ordered the Möbellager workers to move to there and live at ul Nadrzeczna 88. Immediately, Machel had them build there four new “bunkers”. This was important, as it allowed the transfer of the elderly and the children, when the “bunkers” in the Möbellager became too crowded. At the beginning of November, a large number of children were sent there.

One such smuggling is described by Leber Brener:

“Children were hidden in coal crates, furniture or wrapped in old clothes. The horse-driven cart was also loaded with a large pile of old clothes. At the entrance to the gate, Machel ordered the bundles of clothes to be unloaded and, while the guards were busy checking their content, Machel whipped the horse and the cart, with the children, rushed inside. This maneuver required steel nerves, and Machel was the man.

A detailed account of the activities in the Möbellager, and the role of Machel Birencwajg, is also provided in the testimony of Leon Silberstein:

“At that time, there was already a Möbellager for the plundered Jewish furniture. It was headed by Machel Birencwajg, who played an important role. My group also worked there.

“When furniture was brought inside the Möbellager, some Jews were also smuggled inside, especially children and elderly people, that is, those who were not able to work and risked being shot dead. Such people were brought in inside cupboards and we drove them inside the Möbellager. That is how we successfully saved a large number of children and elderly people, who for sure, would have been selected during an ‘Akcje’.”

At all times, Machel was in contact with the underground in the ghetto and was a key man of ŻOB (Jewish underground movement).

Clandestine activities, crucial for the underground, were carried out in the Möbellager. False identity cards (Kenkarte) were printed allowing people to escape to the “Aryan side”. Hand grenade parts were made there and, later, assembled in the “Small Ghetto” under the guidance of Heniek Wiernik. Some of these grenades had been smuggled out and sent to the Warsaw Ghetto, where they were used against the Germans during the 19th April 1943 uprising.

Living conditions in the Möbellager were not as drastic as in other forced labor camps, such as in the HASAG camps outside of the city. Nevertheless, food was rationed and every workshop worker received his meager daily portion. This posed a problem for the families hiding in the “bunkers”, since they were clandestine residents. It became even more critical after the 22nd September 1942 deportations, when a large number of people unexpectedly flocked into the Möbellager and Machel had to build new “bunkers” for them. Thus, after a hard day’s work, and waiting for darkness to fall, Machel and his elder brother Pinchas went from “bunker” to “bunker” and gave away a part of their food portion to those hiding, brought them fresh water and carried away their waste.

On the 8th June 1943, Hauptmann Paul Degenhardt, with his Schutzpolitzei, having been tipped by a Jewish informer, burst inside the Möbellager aiming to liquidate it. He shouted out an order to get Machel and his family. Machel quickly realised that he was in danger, and ran to the second yard to hide. “They’ll never get me alive”, he said to colleagues as he fled.

During their search, they found his 72-year-old mother Bajla, hiding in a public toilet in the second yard. They beat her cruelly, so she would reveal Machel’s whereabouts. People in the first yard heard her screaming “Bitte nicht schiessen, nicht schiessen”, as she desperately pleaded for her life – Degenhardt killed her.

They then found Machel’s wife, Hadassah (Hania) nee Feldman. They took her to the Zawodzie prison from where she was later taken to the Jewish cemetery and was murdered there together with friends.

Pinchas, with others, was standing in a row, while the search continued. He was eating his new Kenkarte with the Aryan name “Piotr Stanislawski” and trying to swallow it. If ever they had found that ID card, they would shoot him dead on the spot. A Schutzpolitzei officer came near and asked him about Machel, and punching him in the face and breaking his teeth. He then pulled out his gun, pointed it diretly at him, but he did not pull the trigger, saying, with a waive of his hand, “Ach, du kommst so wie so Um”, (You will perish anyway.). He put the pistol back into his holster. Pinchas was taken to the Gestapo. At night, he jumped out of the first floor window onto the top of a tree below and ran to hide in the “Small Ghetto”.

Colleagues decided that Machel would now be safest outside of the Möbellager. So they resorted to a well-tested technique – they smuggled him out inside an empty cupboard in a horse-driven cart. As they approached the gate, Machel shouted to friends below, “Ratujcie się, ratujcie się !” (“Save yourselves! Save Yourselves!”). He somehow felt that he would never see them again.

He went into hiding on the “Aryan side” of the city, in the apartment of a Pole whom he knew and trusted. This young man, ever since he was a teenager, worked for many years at the Birencwajg’s store and workshop on Aleja 10. He earned a decent living and was able to provide for his family. Soon after, however, he blackmailed Machel by asking him for money. At one point, Machel summoned Leon Zylbersztajn to bring him some jewellery to satisfy the Pole’s demands.

Even in such a desperate situation, the odds had been in Machel’s favour. He had a Kenkarte with a fake Polish name, allowing him to travel outside of the ghetto. He did not look Jewish, and he spoke and wrote Polish like a a non-Jew. Moreover, he underwent surgery so as to mask his circumcision. He could have easily survived the war, just like his cousin Jankev (Mojs) Rajch and Berek Wajsberg, who both fled to Switzerland and survived . But he stubbornly refused, saying that he would not abandon his beloved. So, he waited, hoping to get a chance to deliver Hadassah from the hands of the Gestapo.

On the 19th of June, a dramatic graffiti from ŻOB appeared on a wall in the ghetto. The scribbled words said, “MACHLA NIEMA , MÖBELLAGER DD, ODCIĘCI DN 19.VI.43”, meaning, “Machel cannot be found, the Möbellager is finished. We are cut off”, followed by the date above. Sometime later (date unknown), two Schutzwerk Politzei broke into the apartment of the Pole. They pulled Machel foutrom under a bed and took him to the Gestapo.

Machel was tortured. As a member of ŻOB, he took orders directly from Mojtek Zylberberg, and knew the names and the hideouts of colleagues, and the caches of weapons and money. Inmates saw him being brought back into his cell unconscious. On the 29th of July, Machel and several inmates, were loaded onto a truck, driven to the Częstochowa Jewish Cemetery and ordered to undress, as was the rule. A supreme humiliation. Machel refused and was cruelly beaten before he was shot dead.

Webmaster’s Comment:

The text on this page was prepared by

Mark Stanislawski-Birencwajg

– Machel Birencwajg’s nephew

and

Wiesław Paszkowski

– historian of the

Częstochowa Historical

Documentation Centre

Mark Birencwajg’s Story

At the time of the liquidation of the ghetto in September 1942, Mark was five-years-old and, together with a group of children, hid in the Möbellager.

One day, in the winter of 1942, he was with his grandmother Bajla, sitting next to the warm stove, when a man suddenly opened the kitchen door from the outside yard. His grandmother instinctively threw herself against him in order to protect him with her body. It was Lange, the Möbellager supervisor. He stood at the entrance showing his sore finger. Bajla went over and treated him with iodine and a band aid.

When the situation became dangerous, with the intention of saving him, Mark’s parents gave him to a Polish family.

Jolanta Altman-Radwańska z"l

Jolanta Altman-Radwańska z”l

Jolanta Altman-Radwańska, following a long, debilitating disease, died on 18th January 2022 in Bonn on the Rhine. In her childhood and adolescence, she was involved with the Częstochowa branch of the Social-Cultural Association of Jews in Poland (TSKŻ).

Jolanta Altman-Radwańska, following a long, debilitating disease, died on 18th January 2022 in Bonn on the Rhine. In her childhood and adolescence, she was involved with the Częstochowa branch of the Social-Cultural Association of Jews in Poland (TSKŻ).

Her father was already a journalist by the inter-war period. He came from a well-known Jewish family, who had been associated with Częstochowa for over a century. Jolanta’s mother came from Lublin, from a patriotic, Polish, Catholic family.

In June 2020, she recorded her memories, filled with names and facts about the years spent in the TSKŻ. Asked to comment on these recordings, her husband, initially sketched her profile, attempting to recreate and understand her extremely interesting, though complex, identity.

Professionally, Jola graduated in history at the Śląsk University in Katowice (1976). Then for eleven years, she worked scientifically, including as the head of the Research Department at the Central Museum of Prisoners of War in Opole-Łambinowice. During those years, she established contacts with a group of several dozen former Polish officers from the World War II period, examining their fate as prisoners of war.

Professionally, Jola graduated in history at the Śląsk University in Katowice (1976). Then for eleven years, she worked scientifically, including as the head of the Research Department at the Central Museum of Prisoners of War in Opole-Łambinowice. During those years, she established contacts with a group of several dozen former Polish officers from the World War II period, examining their fate as prisoners of war.

Following the forced aggravated political situation in her country, she emigrated to Germany at the end of the 1980s. There, she resumed her work in the field in which she had begun. She continued collecting material for her doctoral dissertation at the University of Bonn, publishing numerous source articles on the fate of prisoners of war, as well as Polish, Ukrainian and Belarusian forced laborers in the Rhineland.

The network of contacts with this group of people, built up over the years, resulted in the organisation of several “Weeks of Meetings”, commissioned by the City of Bonn in the years 2000-2006. These was a strong media extraction and recalling of the difficult fate of these people during their forced stay in the city during the war years.

Submitted by:

Dr. Roman Radwański PhD.

English translation by

Andrew Rajcher

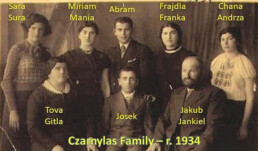

The Czarnylas Family

The Czarnylas Family

- a tribute to the maternal side of his family by Alon Goldman

The Czarnylas Family Before World War II

My mother was born on 1st April 1918 in Pajęczno, the sixth daughter of Jakub-Jankiel Czarnylas and Tova Gitla Czarnylas (née Rząśyńska).

Jakub-Jankiel Czarnylas, my grandfather, was also born in Pajęczno on 15th June 1886, to Icek Czarnylas and Frajdla Czarnylas (née Lipszyc), the fifth of their children.

From documents, which I found in the National Archives in Częstochowa, I learned that my grandfather Jakub-Jankiel had six brothers and sisters, who were all born in Pajęczno.:

Jakub-Jankiel, my grandfather, was born on 15th June 1886. His siblings were:

- Szandel, born 17th May 1873

- Abram, born 12th May 1875

- Esther, born 24th March 1878

- Hersz-Herszlik Fajbusz, born on 22nd January 1880

- Aron, born on 19th September 1882

- Nacha, born 1st May 1891

On 6th November 1908, my grandfather Jakub married Tova Gitla Rząśyńska, born 7th November 1886, in Pajęczno, the daughter of Gabriel and Mindla (née Buchman) Rząśyński.

I know nothing about the childhood of my grandparents and their family in Pajęczno, nor where they lived and what their parents did .

My great-grandfather Icek Czarnylas (my grandfather Jakub’s father) died at the advanced age of eighty-two in Pajęczno, on 16th February 1935 (Record No. 1/1935). he was buried in the local cemetery, of which no trace remained after World War II. From his death certificate, I learned that he was born in 1853 to Jakub-Jankiel Czarnylas and Sarah-Sura Czarnylas (née Bursztyn), both permanent residents of Pajęczno. I know nothing about my great-grandmother Frajdla-Freida (Icek’s wife) nor about when and where she died.

My grandparents, Jakub and Tova Gitla had seven children, all born in Pajęczno :

- Frajdla (Franka), born 16th February 1910

- Abram, born 14th November 1911

- Chana (Andrza), born 15th September 1914

- Bejnusz, born 1914, died 13th November 1915

- Miriam (Mania), born 13th December 1916

- Sarah-Sura, my mother, born 1st April 1918

- Joseph-Josek, born 20th April 1920

- Mosze, born July 1922, dec. 20th Sept. 1922

Due to the economic situation between 1920 and 1925, I do not know exactly when my grandfather Jakub and his family moved from Pajęczno to Częstochowa .

My grandfather Jakub was a successful businessman. He owned a sawmill, traded in lumber and, as well as other businesses. was a partner in a mirror manufacturing factory.

In Częstochowa, the Czarnylas family lived in a building owned by the family at ul. Katedralna 4, (on the corner of ul. Ogrodowa). In May 1939, together with two partners, Jakub Czarnylas purchased the building at ul Katedralna 8 in Częstochowa.

I know very little about my mother’s childhood in Czestochowa. Financially, the family was wealthy and lacked for nothing. A nanny lived with them, who took care of all their needs. Sara attended a high school for girl, and was a member of the Hashomer Hatzair Zionist youth movement. Her sisters, Mania and Franka, joined the Betar Zionist youth movement.

When she was 16 or 17 years old, she first met my father, Jerucham Goldman, who lived on the parallel street (at ul. Fabryczna 22 which, today, is ul. Mielczarskiego 22).

In 1933, her brother Abram immigrated to Israel in order to study at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

From research I carried out at the Pajęczno civil registry office, in the National Archives in Częstochowa and other places, I was able to find some information, in the period prior to World War II, about family members of my grandfather Jakub Czarnylas.

On 20th February 1893, in Pajeczno, his sister, Szandel Czarnylas, married Szaja Heller, who was born in Będzin on 23rd November 1869 and died on 10th September 1932.

In 1900, his sister, Esther Czarnylas, married Szlama Joskowicz, who was born in Będzin on 22nd November 1874. The couple had three children: Sarah born 23rd October 1902, Israel Lejbusz born 22nd April 1906 and Ruchla Frajdla born on 3rd October 1911. Esther and Szlama’s son, Israel Lejbusz married Ruchla Matla and, in 1934, they had a son David.

On 28th October 1903, in Pajeczno, my grandfather Jakub’s brother, Hersz-Herszlik Fajbusz Czarnylas, married Hanah Broda). Her family was also from Pajęczno and the couple had four children, all born in Pajęczno:

- Sara, born 28th October 1903

- Bejnusz, 10th April 1907 – 11th June 1910

- Miriam-Maria, born 30th June 1908

- Freida-Frajdela, born 28th September 1909

Hersz Fajbusz’ wife, Hanah, died on 21st January 1911 at the age of only twenty-eight. Two years later, on 22nd April 1913, Hersz Fajbusz married again, this time to Rebecca Minc of Zabkowice. This was also Rebecca’s second marriage. She had a son from her first marriage, Binem, who was born on 7th October 1907.

In Pajęczno, grandfather Jakub’s brother, Aron Czarnylas, married Chaja Ita née Abramowicz and, in Pajęczno, the couple had three children;

- Malka, born on 1st July 1900

- Frajdla, born on 8th May 1910

- Abram,born on 22nd May 1912

Grandfather Jakub’s sister, Nacha Czarnylas, married Jakub-Jankiel Lieberman, a merchant and one of the leaders of the Pajęczno Jewish community. In Pajeczno, the couple had eight children:

- Josef

- Isac

- Szmuel (Szmil)

- Frajdla born 24th June 1916

- Abram, born 10th March 1919

- Mosze Chaim, born 5th October 1921

- Aron, born 9th October 1922

- Meir, born 25th March 1925

The Holocaust

Luck did not play out for the Czarnylas family. On 3rd September 1939, Częstochowa was occupied by the Germans, who also occupied Pajęczno on 4th September 1939. From moment, the lives of the population, in general, and the Jewish population in particular, turned into Hell.

Shortly after the conquest of Częstochowa, in November 1939, my father said to my mother, “This will not end well and we must flee”.

Both, young and in their early twenties, were still unmarried. They came to their parents and offered to join them in escaping to the Russian side of the border, to Lwów, a city which my father had known from his electrical engineering internship, which he had completed just before the outbreak of the war. Their parents refused, claiming that the war would end soon and that there was no point in leaving Poland. In spite of everything, my parents decided to flee and, through difficult means, managed to escape to the Russian side of the border and to reach the city of Lwów. Grandfather Jakub Czarnylas tried to persuade them to return to Częstochowa and asked a rabbi to go on a mission to Russia to find them in Lwów and persuade them to return home to Częstochowa. The rabbi went to Lwów, met them and conveyed the message from their parents. He also gave them a sum of money which the parents had sent for them.

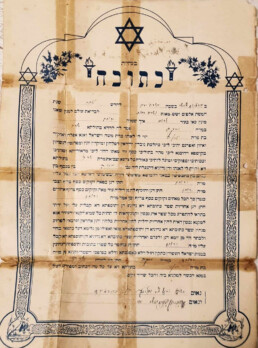

My parents, who were convinced that there was danger in Częstochowa, asked the rabbi to marry them in a Jewish ceremony. So, on 22nd December 1939, my parents were married in a Jewish wedding in Lwów. The rabbi returned to Częstochowa and informed their parents of their marriage.

In 1940, my father found work in a quarry and my mother also found temporary work which enabled them to survive. All the while, they were looking for ways to bring their parents to the Russian side of the border – but without success.

When the Germans invaded Russia in June 1941, my parents fled eastward towards Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan and, after some wandering, came to Tashkent and, from there ,to Samarkand.

In Samarkand, my father found a job in a beer factory. During his work, he fell ill. But, at that time, he could not afford to get sick and so he continued to work. It later turned out that, at that time, he had contracted tuberculosis. How he managed to overcome the disease no one knows .

Life in Russia was not easy to say the least. It was a Hell on Earth. In 1942, when word spread about the possibility that Anders’ Army (Polish Armed Forces in the East) would move westward outside Russia’s borders, my father took advantage of his profession as an electrical engineer and managed to enlist in Anders’ Army in the hope that he could leave Russia with the army .

After a long journey through Iran, Iraq and Lebanon, in May 1943, my father arrived in Mandatory Palestine (now Israel) with Anders’ Army.

My mother managed to leave Russia as the wife of a soldier in Anders’ Army and came to Mandatory Palestine with the Tehran children.

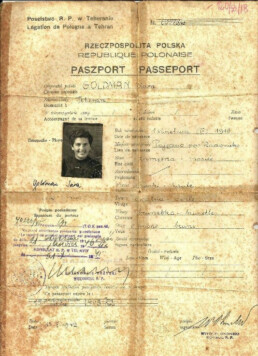

On her way to Palestine, in October 1942, the Polish consulate in Tehran issued her with a passport with which she was allowed to enter Mandatory Palestine .

Pic left: Passport, issued by the Polish consulate in Tehran on 15th October1942, in the name of Sara Goldman née Czarnylas.

In July 1943, Anders’ Army left Palestine for Egypt and, later, for North Africa, joining the Allied forces in Italy. At the end of the war, my parents met again in Palestine.

Arriving in Palestine, my mother met up with her brother Abram Czarnylas. At that time, he was the only family member known to have survived.

I do not know much about what happened to my family members who remained in Poland – in Pajęczno and in Częstochowa. I found the name of my grandfather Jakub Czarnylas on a list of forced labourers in the HASAG Pelcery forced labour camp in Częstochowa and, apparently, the rest of the family were also forced labourers in this factory, which manufactured ammunition for the German war effort.

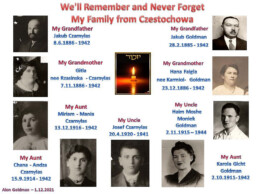

Almost the entirety of my mother’s family who remained in Częstochowa – her father Jakub, her mother Gitla and her sisters Miriam (Mania) and Hanah (Andrza) – found their deaths, during the liquidation of the “Big Ghetto” in September-October 1942, either in Częstochowa or in Treblinka.

According to testimonies from survivors, Jozef Czarnylas, my mother’s younger brother, was shot in the head by a German soldier in June 1941, when he lit a cigarette without permission while working at the Möbellager. This was a warehouse, on ul. Wilsona in Częstochowa, where the Germans stored furniture removed from Jewish homes in the ghetto.

Of the whole family, only one sister, Frajdla (Franka), survived the torment of the Holocaust. According to some documents, it seems that, for a certain period, she was in the Łódź ghetto, from where she returned to Częstochowa. From April 1940 until 16th January 1945, she toiled in HASAG Pelcery of Częstochowa. She was then sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, from where she was moved to the Burgau concentration camp, a sub-camp of Dachau. From there, she ended up in the Turkheim concentration camp, from where she was liberated on 27th April 1945.

Of the whole family, only one sister, Frajdla (Franka), survived the torment of the Holocaust. According to some documents, it seems that, for a certain period, she was in the Łódź ghetto, from where she returned to Częstochowa. From April 1940 until 16th January 1945, she toiled in HASAG Pelcery of Częstochowa. She was then sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, from where she was moved to the Burgau concentration camp, a sub-camp of Dachau. From there, she ended up in the Turkheim concentration camp, from where she was liberated on 27th April 1945.

Frajdla (Franka) was the only one of the whole family to return, after the end of the war, from the concentration camp to Częstochowa, only to see that no one from the Czarnylas family from Pajęczno and Częstochowa remained alive. As many did, Abram and Sarah in Israel and Frajdla (Franka) in Poland also began looking for survivors until they found each other. In 1948, Frajdla (Franka) left Poland and immigrated to Palestine to reunite with her brother and sister.

I was able to find very little information about the fate of the family members, brothers and sisters of my grandfather Jakub Czarnylas , who remained in Pajęczno.

During the German occupation, Jakub Lieberman, husband of Nacha Czarnylas (my grandfather’s sister) who was one of the leaders of the Pajęczno community, was appointed Chairman of the Judenrat. This was a thankless task, which required him to relate to all refugees from nearby villages and to supply the Germans with labour quotas.

From the beginning of the occupation, the Germans occasionally demanded work crews for camps in the Poznan area. More than once, the Judenrat succeeded in bribing German officials in order to cancel any deportation.

In 1941, the Pajęczno ghetto was established in the poorest part of the city.

Penalty taxes were repeatedly imposed upon the residents of the ghetto. The looting of Jewish property in the ghetto reached its peak in the spring of 1942, two weeks before Passover, when German police went from house to house, beating the residents, taking some as hostages and robbing them of their possessions. In the spring and summer of 1942, the Judenrat was required to hand over certain Jews to the Gestapo. In June 1942, the Chairman of the Judenrat, Jakub Lieberman was himself arrested along with eleven other Jews. They were all murdered by German policemen and, in their place, the Germans appointed the butcher Berl Mrówka to head the Judenrat. According to testimony given to Yad Vashem, Jakub Lieberman and other members of the Judenrat were taken to the Łódź ghetto, where they were executed by hanging.

The liquidation of the Pajęczno ghetto began on 19th August 1942. About 1,800 Jews of the ghetto were brought to a church and were held there for several days under extremely difficult conditions. During those days, another 140 Jews, who were found in hiding places in the ghetto, were forced to join them. On 21st August 1942, the Germans murdered all the elders in the churchyard, including Mrówka, the head of the Judenrat.

On 22nd August 1942, most of the Pajęczno Jews were deported to their deaths in the Chełmno extermination camp. The rest were sent to the Łódź ghetto. Of all the members of the Lieberman family, the only one to survive the Holocaust was Aron Lieberman. On 19th December 1939, he was imprisoned in Pajęczno, from where he moved about between concentration camps – to Monowitz, Fogenbord, Posen (Poznań), Buchenwald and Auschwitz.

Following his liberation in 1945, in a chance meeting with one of his townspeople, he realised that none of his family members had survived the Holocaust and so he had no reason to return to Pajęczno.

Pic below: Aron Lieberman’s ex-concentration camp identity card

Life After the Holocaust

Adapting to life in Israel was not easy for my parents, both in terms of housing and work. They had to cope with a new place, a new language and a difficult economic situation in those first years. On 9th July 1948, my older brother was born and was named Jacob, after his two grandfathers, who perished in the Holocaust. After his birth, my parents bought a three-room apartment in Ramat Gan, where they lived all their lives. I was born in this home on 8th August 1953 .

My father Jerucham began his career in Israel with occasional jobs in the electrical field. At one time, he ran a garage specialising in automobile electronics, until he found employment, in large factories, in his profession as an electrical engineer. In 1958, he was appointed Chief Electrical and Maintenance Engineer of the Beilinson Hospital, the biggest hospital in Israel. He worked until he retired in 1986. After retiring, he continued to work for several more years as a consultant to a network of nursing homes and a private hospital in Bnei Brak.

My father Jerucham began his career in Israel with occasional jobs in the electrical field. At one time, he ran a garage specialising in automobile electronics, until he found employment, in large factories, in his profession as an electrical engineer. In 1958, he was appointed Chief Electrical and Maintenance Engineer of the Beilinson Hospital, the biggest hospital in Israel. He worked until he retired in 1986. After retiring, he continued to work for several more years as a consultant to a network of nursing homes and a private hospital in Bnei Brak.

All those years, my mother was a housewife and, when my brother and I were already grown up, she operated a sewing shop in a large textile chain in Israel.

My parents were very happy when they saw the establishment of the next generation of the Czarnylas and Goldman families in Israel. My brother Jacob married Yehudit (née Mendelson) on 13th October 1971. They have two daughters, Liat and Karen, and four grandchildren. I married Dorit (née Sussman) on 16th October 1986. We have three daughters – Tal, Dana and Noa and currently three granddaughters.

My mother, Sarah Goldman (née Czarnylas), passed away on 8th October 1988 and my father Jerucham Goldman passed away on 1st December 2000.

Frajdla (Franka) (née Czarnylas), after immigrating from Poland to Israel, lived in Tel Aviv. She first married in 1950, a marriage that did not last. In 1957 she remarried. Throughout her life, she suffered greatly from health problems caused by everything which she had gone through in the concentration camps. She had no children. She died in Tel Aviv on 10th March 1978.

Abram Czarnylas, who came to Israel as a student, married Esther (née Ha’Ivri). They had three children – Prof. Josef Czarnylas (a cardiologist, named after his uncle, who was shot to death in Częstochowa), Nira and Nava. They have eight grandchildren and fourteen great-grandchildren. Abram was a businessman in the field of building materials and real estate. He died of a heart attack in Israel on 24th December 1960, at the age of only forty-nine.

Abram Czarnylas, who came to Israel as a student, married Esther (née Ha’Ivri). They had three children – Prof. Josef Czarnylas (a cardiologist, named after his uncle, who was shot to death in Częstochowa), Nira and Nava. They have eight grandchildren and fourteen great-grandchildren. Abram was a businessman in the field of building materials and real estate. He died of a heart attack in Israel on 24th December 1960, at the age of only forty-nine.

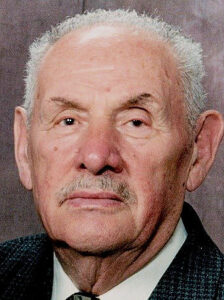

Aron Lieberman (son of Nacha Lieberman – née Czarnylas) was the only survivor of his family. After being released from Auschwitz and, after a chance meeting with his townspeople in a displaced persons camp, he realised that no one from his family was alive and so he went to Eindhoven, in the Netherlands. There, he was adopted by a Dutch family and found a job at Philips Electric. In 1954, he came to Winnipeg, Canada, and, in 1958, he married Dora Wise. Aron had two sons, Jeffrey and Gary, and five grandchildren. After searching for several years, the cousins Aron, Sarah, Abram and Freidla (Franka) found each other. In October 2021, he celebrated his 99th birthday.

Aron Lieberman (son of Nacha Lieberman – née Czarnylas) was the only survivor of his family. After being released from Auschwitz and, after a chance meeting with his townspeople in a displaced persons camp, he realised that no one from his family was alive and so he went to Eindhoven, in the Netherlands. There, he was adopted by a Dutch family and found a job at Philips Electric. In 1954, he came to Winnipeg, Canada, and, in 1958, he married Dora Wise. Aron had two sons, Jeffrey and Gary, and five grandchildren. After searching for several years, the cousins Aron, Sarah, Abram and Freidla (Franka) found each other. In October 2021, he celebrated his 99th birthday.

All these years, we have lived in the knowledge that, with the exception of the four, Abram Carnylas, Freidla-Franka (née Czarnylas), Sarah GOLDMAN ( née Czarnylas) and Aron Lieberman, all the other members of the Czarnylas family perished in the Holocaust.

Complete and Unfinished

In 2014, during one of my visits to Poland, I met Ms. Anna Przybyszewska, from the Genealogy Department of The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, in order to try to find more information about my Czarnylas family members from Poland. Unfortunately, at this meeting, no new information was revealed.

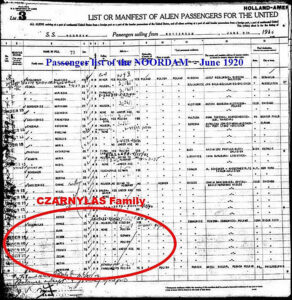

However, a big surprise awaited me in early 2015, seventy years after the end of World War II. I received an email from Anna Przybyszewska in which she wrote that she had come across a passenger list from a ship called the Noordam, which had arrived, on 9th June 1920, at Ellis Island in the United States from Rotterdam in the Netherlands. One of the passengers on this ship’s manifest was Rebecca Czarnylas (aged thirty-five). She was a native of Zabkowice, who had lived in Pajęczno and had arrived with six children – Sarah (aged 17), Binem (13), Maria (11), Frania (10), Zelma (8) and Motka (7). Her husband, Harry Lass, a baker, who lived at 603 Iowa St., Sioux City, Iowa, was waiting for her on the platform, and he was the one who paid for the passage.

However, a big surprise awaited me in early 2015, seventy years after the end of World War II. I received an email from Anna Przybyszewska in which she wrote that she had come across a passenger list from a ship called the Noordam, which had arrived, on 9th June 1920, at Ellis Island in the United States from Rotterdam in the Netherlands. One of the passengers on this ship’s manifest was Rebecca Czarnylas (aged thirty-five). She was a native of Zabkowice, who had lived in Pajęczno and had arrived with six children – Sarah (aged 17), Binem (13), Maria (11), Frania (10), Zelma (8) and Motka (7). Her husband, Harry Lass, a baker, who lived at 603 Iowa St., Sioux City, Iowa, was waiting for her on the platform, and he was the one who paid for the passage.

Another look at Ellis Island’s website, of records of entry to the US, yielded another surprise. On the passenger list of that same ship, the Noordam, arriving in the USA from Rotterdam on 29th October 1920, was Hanah Czarnylas (35) from Pajęczno. She appears with with three children – Malka (aged 18), Frida/Trailo (11) and Abram (9). Her husband, Archie Lass, a baker, who lived at the same address as Harry Lass, 603 Iowa St., Sioux City, Iowa, is also listed as waiting for her on the platform and he also paid for the family’s trip.

Are Harry Lass and Archie Lass, brothers of the Czarnylas family from Pajęczno? Is Harry Lass perhaps Hersz Fajbusz Czarnylas and is Archie Lass perhaps Aron Czarnylas, the brothers of my grandfather Jakub Czarnylas?

In an attempt to solve the mystery, I went back to check the certificates (birth, marriage) of Czarnylas family members from the National Archives in Częstochowa. Given that the passenger list records the age of the passengers when arriving in the United States, together with the place of birth and husband’s occupation, I reasoned that we could compare the details and then determine if the immigrants to the USA were possible family.

From the examination of the documents in my possession, I understood very quickly that the three children (Sarah, Maria and Frania), who came with Rebecca, WERE the children of Hersz Fajbusz Czarnylas, from his marriage to Hana Broda, and that Malka, Frida and Abram were the children of Aron Czarnylas from his marriage to Hana Ita Abramowicz.

I also discovered that Hana Czarnylas (nee Broda) had died in Pajęczno on 21st March 1911 and that Hersz Fajbusz Czarnylas remarried Rebecca Minc of Zabkowice on 13th April 1913. (She was the woman who came to the United States with the children.)

But who were the other three children on the list who came with Rebecca? How do I verify beyond any doubt that Harry and Archie are the brothers of my grandfather Jakub Czarnylas?

My search on the JewishGen website led me to Katherine Lass from St. Louis, USA, who was looking for information about the Czarnylas from Zabkowice. I contacted her and, after an email exchange and phone calls, the mystery was solved. She told me that Binem (one of the children) was Rebecca’s son from her first marriage and was Katherine’s father. According to what Binem had told Katherine, they were from a small town in Poland and that their family name in Poland was “Black Forest” which, in Polish, is “Czarnylas”. Katherine’s grandmother Rebecca was from the Minc family and Zalma (Sam) and Motke (Max) were children born from Rebecca’s marriage to Harry. In response to my question if she had contact with the rest of the family, she answered that she had no contact, but knew that one cousin, Kenneth Lass, was living in Nashville, Tennessee.

My search on the JewishGen website led me to Katherine Lass from St. Louis, USA, who was looking for information about the Czarnylas from Zabkowice. I contacted her and, after an email exchange and phone calls, the mystery was solved. She told me that Binem (one of the children) was Rebecca’s son from her first marriage and was Katherine’s father. According to what Binem had told Katherine, they were from a small town in Poland and that their family name in Poland was “Black Forest” which, in Polish, is “Czarnylas”. Katherine’s grandmother Rebecca was from the Minc family and Zalma (Sam) and Motke (Max) were children born from Rebecca’s marriage to Harry. In response to my question if she had contact with the rest of the family, she answered that she had no contact, but knew that one cousin, Kenneth Lass, was living in Nashville, Tennessee.

According to Jewish tradition, it is customary to write the Hebrew name and the father’s Hebrew name on a person’s cemetery gravestone. On the one hand, I have the Polish documents with the Hebrew names that were used in Poland but, on the other hand, I have the names that were often written incorrectly when arriving in the US, along with the new names which they adopted. In order to further my investigation, I had the idea to try to locate the burial places of Harry and Archie and to see what is written on their gravestones, and whether the name of their father Isac appears on their gravestones.

My efforts bore fruit and in the Independent Farane Jewish cemetery in Sioux City, Iowa, I found their graves. With the help of Ms. Rhonda Menin, the cemetery director, I obtained pictures of the three graves:

Harry P. Lass – died 7th March 1952 – Section A, Grave 1411

On his tombstone, written in Hebrew, is Zvi Hersz son of Isac/Yitzchak, next to the name Harry, the name which he adopted in the USA. Zvi is Hersz, so Harry’s Hebrew name, year of birth and father’s name matched the documents from Poland.

Harry’s wife Rebecca Lass – died 23rd May 1958 – Section A, Grave 1412

Rebecca’s father’s name, David, which appears on the tombstone, is the same as her father’s name which appears on her marriage certificate to Hersz Fajbusz (Harry) from Poland .

Archie Lass – died 4th November 1941 – Section A, Grave 1414

On his tombstone is written, in Hebrew, Aron son of Isac/Yitzchak Lass.

Exactly when Hersz Fajbusz and Aron, my grandfather’s older brothers, immigrated to the United States, I do not know.

My mother never talked about family in the USA and I guess, until the day she died, she did not know about all of it. So all these years we lived thinking that the whole Czarnylas family had perished in the Holocaust. In my estimation, they left for the USA sometime after 1913 and, after establishing themselves, in 1920, they brought their wives and children.

Thanks to difficult genealogical research, I found some of the Czarnylas descendants all over the United States in such places as Dallas, Houston, El Paso, Plano, Chicago, Springfield, Nashville, Beverly Hills and Los Angeles.

When I contacted them, it was a huge surprise and big shock for them – the discovery of an unknown chapter in their family history which begins in Pajęczno in Poland, about which they knew nothing.

This is where my story ends – the story of the Czarnylas family from Pajęczno and Częstochowa, Poland. I do not know everything and there are many things which I will never know .

Webmaster’s Comment:

The contents on this page,

about the maternal side of his family

has been supplied by

Alon Goldman,

Chairman of the

Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel,

Vice-President of the World Society of Częstochowa Jews & Their Descendants.

Below, he writes a little about himself:

As in many homes of Holocaust survivors, in my home, my parents hardly talked at all about the Holocaust. In fact, we, the second generation, were not so interested in the subject.

As a child, at home, I spoke to my parents in Polish as a first language, which I had learned from my mother and father naturally (a language I speak to this day, even though I never formally learned it in school and which I call “Intuitive Polish”, because I can’t explain why I say things the way I say them).

We lived in our world, as Israelis proud of the free State of Israel, and facing the needs for its existence, seeing as how it is surrounded by Arab countries wishing to destroy it.

Like most youth in Israel, I grew up in a modest home. At the age of 18, I completed my high school education and, in 1972, I enlisted in the Israeli army like most Israeli youth. During the Yom Kippur War in 1973, I served as an officer in the 401 Tank Brigade in Sinai and, after my release from regular service, I continued in the reserve service for many years, from which I was discharged with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

At the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, I studied for a Bachelor’s Degree in Economics and, at Tel Aviv University, I completed a Master’s Degree in Business Administration. Concurrently with my studies, I worked at Bank Leumi, where I was promoted to very senior management positions.

When my mother passed away in 1988, I suddenly realised that I knew almost nothing about my roots and that I also had no one to ask, since almost her entire family perished in the Holocaust and those of her family members, who survived, had already passed away.

This was the beginning of my journey to discover my roots and identify as part of the heritage left to me by my father and mother. The journey continued in earnest several years later.

In 2006, I was invited to join the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel. In 2011, I was elected Chairman of the Association and then also to the office of Vice-President of The World Society of Częstochowa Jews and Their Descendants.

During this time, my ties with Poland have strengthened and so the journey to discover my roots has intensified .

Sam Krycer z"l

Sam Krycer z"l

- Częstochowa-born centagenarian and Australian World War II veteran

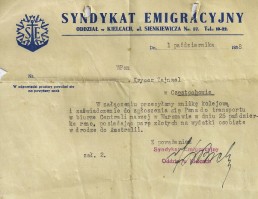

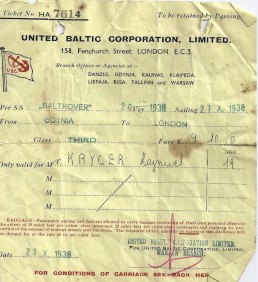

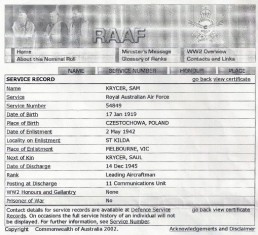

Sam (Zajnwel) Krycer z”l was born in Częstochowa on 17th January 1919. He arrived in Australia on 11th December 1938, settling in Melbourne. During World War II, he served in the Royal Australian Air Force.

Sam (Zajnwel) Krycer z”l was born in Częstochowa on 17th January 1919. He arrived in Australia on 11th December 1938, settling in Melbourne. During World War II, he served in the Royal Australian Air Force.

On 25th April 2019, at 100 years of age, he represented the Royal Australian Air Force and led the annual ANZAC Day parade (Australia’s memorial day).

Sadly, Sam passed away on 31st July 2019.

Between his participation in the parade and his passing, Sam agreed to talk about his life with our World Society webmaster, Andrew Rajcher.

Click HERE to read Sam describing his long, eventful life.

SAM AND HIS FAMILY

LEAVING CZĘSTOCHOWA FOR AUSTRALIA

MILITARY SERVICE IN WORLD WAR II

ANZAC DAY – 25th APRIL 2019 (Australia’s memorial day)

In 2019, Sam was given the honour of leading the annual march, from Melbourne’s downtown area to the city’s Shrine of Remembrance.

Webmaster’s Comment:

The pictures in this tribute page

have been supplied by Sam’s sons

David Krycer and Colin Krycer.

I thank them sincerely for arranging

my interview with their late father and

for supplying the pictures appearing here.

In May 2019, it was truly an honour

for me to sit with Sam, in his home,

and to listen to his eventful story.

Harry Rapaport's Family

Harry Rapaport's Family

- a Story of Tragedy and Survival

Harry Rapaport

Webmaster’s Note:

To anyone who has attended our Reunions, Harry and his wife Penny will have become familiar faces to you.

In this video, recorded on 1st May 2019 to mark Yom Ha’Shoah, Harry tells the story of his and Penny’s families – their Holocaust tragedies and stories of survival, to New York State Legislators, as part of their Holocaust Program.

His eloquence is highly moving and those of us who are descended from Holocaust survivors, as are Harry and Penny, will recognise many of the elements of Harry’s story in our own stories also.

From Harry Rapaport:

I’m retired as a court reporter from the US District Court in NY.

After bringing back Torah Scrolls from Częstochowa in 1988 & 1989, I began to tell the story of the rescue of the Torahs and the restoration of 15 scrolls, which mushroomed into my giving combined lectures of the story of the Torahs in conjunction with my family’s suffering and surviving the Częstochowa Ghetto, the Łódż Ghetto, Treblinka, Auschwitz and other camps, and the liberation by Allied troops in 1945, including their search after liberated for any relatives that may have also survived. Finding no one, I speak about their life in the DP Camps and arrival in the US.

I also speak about my dad’s father being the first Jew killed on “Bloody Monday”, 4th September 1939, and his burial in the Częstochowa Jewish cemetery, and my dad’s arrival to Treblinka on 2nd October 1942, with his 69 year old mother, his pregnant wife, his 11 year old daughter Esterka, their immediate death in gas chambers, and fate that my dad had the luck to sneak into a work detail (sorting clothes) while naked and only meters away from gas chamber; and his escape and plans for escape from Treblinka.

I lecture on the subject whenever asked, never taking any fee. It’s a legacy I inherited from my dad, Moishe RAPAPORT z’l.

The Szlam Family

The Szlam Family

Righteous Stanisława Włodarz Granted Honorary Israeli Citizenship

On 29th January 2013, in a ceremony conducted at the Częstochowa Town Hall, Honorary Citizenship of Israel was granted to Stanisława Włodarz, a Częstochowa resident and already a Righteous Among the Nations.

On 29th January 2013, in a ceremony conducted at the Częstochowa Town Hall, Honorary Citizenship of Israel was granted to Stanisława Włodarz, a Częstochowa resident and already a Righteous Among the Nations.

The presentation was made to her by Zvi Rav-Ner, the Israeli Ambassador to Poland, in the presence of the Mayor of Częstochowa, Krzysztof Matyjaszczyk, local government representatives and students from several Częstochowa schools.

Mrs.Włodarz and her parents, Marianna and Stanisław Szlam, were honoured by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations for aiding Jews who had escaped from a transport heading to Treblinka.

In the winter of 1942, the Szlam family took two Jews into their home – Mosze Lichter and his cousin, Mordechaj. The later took in the men’s cousins, Rózia and Cesia. As a teenager at the time, Stanisława would bring them their meals and would spend time with them.

Prior to leaving for Israel, Mosze Lichter wished to give all his material assets to the Szlam family – however they declined to accept it. After many years, those who were saved applied to Yad Vashem to have the family honoured with the title of Righteous Among the Nations.

Not long ago, Mordechaj Lichter’s daughter, Michaela Liniat, made the application to have Honorary Israeli Citizenship granted to to Stanisława Włodarz.

The World Society gratefully acknowledges

and sincerely thanks

![]()

Telewizja Orion

and

Czarek Szymański

for permission to use the video

which appears on this page.

Leon Silberstein z"l

Leon Silberstein z"l

- Nothing Short of a Hero

While the Holocaust took the lives of over six million Jews, it also obliterated the dreams and innocence of the survivors left behind. For over sixty years, one survivor, Leon Silberstein believed his tormented past should remain a secret. Today, he wants to speak about the unimaginable events he observed and participated in to clear his conscience and validate his past. This is a tribute to a man, who displayed remarkable courage in the face of adversity and went beyond normal means to ensure the safety of those he loved.

While the Holocaust took the lives of over six million Jews, it also obliterated the dreams and innocence of the survivors left behind. For over sixty years, one survivor, Leon Silberstein believed his tormented past should remain a secret. Today, he wants to speak about the unimaginable events he observed and participated in to clear his conscience and validate his past. This is a tribute to a man, who displayed remarkable courage in the face of adversity and went beyond normal means to ensure the safety of those he loved.

The chronology of Mr. Silberstein’s experiences throughout the Holocaust is of less consequence than the recurring themes that still plague him. It appears that Mr.Silberstein still questions his own survival. “I shouldn’t have lived,” he mutters often. Despite his feelings of disbelief, he is still aware that he made conscious choices to shape his past. These choices are the root of remorse for him.

Behind the frail and soft-spoken man we see today, Mr. Silberstein was extremely talented and brave as a young man. Mr. Silberstein was born on October 28 in 1905 in the Polish city of Piotrków. He was born into a family of eleven children. His mother died when he was thirteen years old. In 1926, at the age of nineteen, he went to Palestine against his father’s wishes. In Palestine, he worked on a farm and declared himself a Zionist. Leon returned three years later to his family in Poland. He sought to return to Palestine, but was drafted into the Polish army.

As a soldier in the Polish army, Mr.Silberstein was stationed in the Polish city, Częstochowa, located southwest of Warsaw. The city was a wealthy industrial centre where Jews worked in many industries, including banking, trading, and crafts. While in Częstochowa, he married a woman named Rose and became a skilled mechanic. With his wife, he opened a three-storey factory that manufactured bicycle parts. Leon had patented many parts himself. While Leon was the mastermind behind the engineering aspect of the factory, his wife took an active role in the financial aspect of the business. His wife went as far as bribing a government official to require that all bicycles must have night lights. As the only bicycle factory able to manufacture such lights, the Silbersteins were able to capatalise on this law and become incredibly successful. Together, Leon and Rose had created the most modern factory in Częstochowa. Sadly, their money and influence could not save them from the wrath of Hitler’s regime.

The city of Częstochowa was invaded by the Germans on 3rd September 1939 and, the following day, more than 300 Jews were slaughtered. Subsequently, all Jewish property was confiscated and 1,000 young Jews were deported to labor camps in August of 1940.

On April 9 1941, a ghetto was created in Częstochowa and was sealed off on August 23. Twenty thousand Jews, from all over were packed into the ghetto. Eventually, the ghetto held more than 48,000 Jews. The ghetto consisted of a large part of the city that included many of the poorer Jewish areas of Częstochowa and few of the wealthier ones. Almost a third of the population had been pushed into an eighth of the city. Three to five families could be moved into two-bedroom apartments. The situation was bedlam. Fortunately, Mr. Silberstein was not limited to the confines of the ghetto.

When the war began, the Germans recognized Mr. Silberstein’s ability as a mechanic and untrained engineer. Although he was Jewish. the Germans had respect for his talent. The Germans dubbed him the “universal tradesman”. It was not long before the Germans had Leon opening safes that held important documents. Mr.Silberstein possessed the incredible ability to visualise solutions to difficult problems even if he was not trained in that particular field. His incredible craftsmanship enabled him to resist living in the ghetto and not carry a blue and white star that identified him as a Jew. This was indeed, a rarity.

Mr.Silberstein’s talent was employed elsewhere. The Germans wanted Mr. Silberstein to build a restaurant for German soldiers in an abandoned building. Before working on the project, he demanded to speak with the commanding officer of the restaurant. Everyone thought he was insane not to just take orders, but Leon thought it was important to understand his client’s taste, therefore making it impossible for the Germans to have qualms with his work. He asked the officer about his childhood and the region from which he was from. Leon deduced that the chief would be indubitably pleased if the restaurant reflected his home town. Besides this, Leon designed an incredible pulley system, where the dirty dishes and food could come up and down from the kitchen in the basement. As well, he sought to make the most cost-effective seating by using as little wood as possible to design tables and chairs.

Mr.Silberstein’s ability as an engineer proved successful and was thus put to work on several projects for the Germans. Hitler’s birthday was approaching and Leon was commissioned to prepare a stage for the band to play on. He was faced with the problem of creating the illusion of a larger space. He did this by using two different colours for the curtains; the lighter would be in front of the darker creating the illusion of depth. His plan was successful. During the project, however, he faced anti-Semitism from a Pole who complained to the Germans that a Jew should not undertake such a project. Leon told the Germans that if the Pole did not stop harassing him he would abandon the project. The Germans sent the Pole away. It was obvious that the Germans could not help but respect such a clever man as Leon.

While Leon’s talent as an engineer was praised, so was his talent for relating to others. Mr.Silberstein was in charge of heading up a group of talented artisans each day, who were highly specialised in various fields. He would pick up twelve to fifteen men and women and take them to work. Work involved clearing furniture from Jewish homes and decorating new German residences. Workers constructed new furniture and buildings. Many served as electricians as well. While he assisted Germans, he was neither servile to the Nazis nor abusive to Jews. For instance, his German officer, Werner once told Mr. Silberstein to whip the Jews that he commanded. He refused and rather picked up a shovel and joined them.

Mr.Silberstein wore two faces as he would like to call it. Not only did he work for the Germans, he worked for the Jewish underground, which was considered at the time to be unthinkable, as the Jews became increasingly few in number and strength. Many of the artisans which Leon commanded were also members of the underground. Oftentimes, they could cover up work they were completing for the Jewish underground, as work they had to do for the Germans. As well, they could get access to German equipment that they could not otherwise use.

Mr.Silberstein wore two faces as he would like to call it. Not only did he work for the Germans, he worked for the Jewish underground, which was considered at the time to be unthinkable, as the Jews became increasingly few in number and strength. Many of the artisans which Leon commanded were also members of the underground. Oftentimes, they could cover up work they were completing for the Jewish underground, as work they had to do for the Germans. As well, they could get access to German equipment that they could not otherwise use.

One of the recurring stories that haunts Mr.Silberstein is that of his nephew, Jerzyk, who like him, was involved with the Jewish Underground. The Jewish Underground gave orders to Leon to kill a German pilot. It was necessary to obtain the pilot’s clothes in order for the Underground to steal a German plane. Leon asked for volunteers to kill the pilot. The boy who offered was his nephew, Jerzyk, a young scholar, not older than nineteen. Jerzyk was anxious to kill a German to compensate for the death of his father, who was hung at Treblinka. The plan was for Jerzyk to kill a German pilot in a nearby park where they met prostitutes. That night, the pilot arrived on schedule around nine o’clock and was seduced by a Jewish woman disguised as a prostitute. Jerzyk came up behind the pilot seated on a park bench and strangled him with a rope. from behind. Jerzyk fled to the forest with six other boys involved with the Underground.

Leon was well aware that the Germans were spying on his operations. It was necessary for him to relocate the boys. He found a deserted warehouse where he hid the boys and Jerzyk. A few days later, a woman and her two sons came from Warsaw to find some money. Leon recognised that they were Jews and told them not to look for money and to stay in the deserted furniture warehouse in the meantime. One of the small boys decided to look for money anyway. He was found and captured by a Pole, who delivered him to the Gestapo, the German police. It is apparent that Leon was near the scene of the arrest and the little boy called out that he knew Leon and where others were hidden. Leon adamantly denied knowing the boy and having the key to the furniture warehouse. While Leon was not taken for investigation, the warehouse was discovered. All of the boys, including Jerzyk, were forced to confess to the murder of the German pilot. They were all killed. The Germans were in such disbelief that a Jew could kill a German, ten other Polish people were forced to die for the crime.

The story of Jerzyk is of great significance and still troubles Mr. Silberstein to this day. Jerzyk’s choice to kill the officer was in essence an opportunity to commit suicide. Both Mr.Silberstein and Jerzyk knew that the punishment of death was inevitable. While Mr.Silberstein has never wished that he was killed, he feels responsible for giving the command and not protecting a family member. Today, a monument in honour of Jerzyk stands today at Beersheva University in Israel.

There were other times that Mr.Silberstein’s life was spared. Once, Leon knew a German officer, who was in love with a Jewish girl. The officer had Leon take the girl out of the ghetto and bring her to him. Leon warned the girl of the danger of the situation, but she was convinced that their mutual love would protect them. This however was not the case. The Gestapo found out and the officer killed the Jewish girl. Despite the cruelty of the officer’s actions, he felt gratitude towards Leon for delivering the girl. A few days later there was a selection for Jews to be killed in the middle of town. This officer grabbed Leon and told him to take his wife out of the selection. They were both saved.

Additionally, his life was spared due to the profound trust and appreciation Leon established with others. Once the Germans wanted to buy coffee, which was only sold on the black market. The Germans asked Leon to carry out the order of purchasing the coffee. Leon was caught carrying the large bag of coffee by the Polish police. He was arrested and taken in for investigation. It was known however at police headquarters that Leon would never confess. He would remain loyal, even if he worked for the Germans. After being imprisoned for a day, a Polish Major confronted Leon. Rather than kill Leon, the Major told him that he needed a Jew, who was as clandestine and loyal as himself. He made Leon work for him.

A few months later, Leon and members of the Eldestenrat (Council of Jewish Elders appointed by the Germans to handle internal Jewish affairs) in the city were given the opportunity to exchange all of their money and goods to go to Palestine. Leon prepared false identification for himself and his wife in order for them to be transported safely. The day on which they were supposed to leave, a German officer made Leon work and complete various projects. Leon was concerned that he would miss the chance to leave, but he was forced to finish. When he was done, he went to pick up his wife to leave for Palestine, but he saw in the centre of town a bunch of opened suitcases with old clothes coming out. Everyone who had signed up to leave for Palestine had been slaughtered. It is still unclear if the German officer intentionally saved Leon and his wife that day by making him stay later. These are questions that Mr. Silberstein can never answer.

In May 1942, there were orders to kill Mr. Silberstein. A German officer named Lasinski told Leon that he had received an order from a high official to kill him. Lasinski told Leon that if he could find another person with the last name, Silberstein he would pretend that he killed Leon. Leon knew another Jew, Igenia Buca, who commanded a squad of Jews for the Germans. Ingenia Buca had a boy under his command with the last name Silberstein. Leon paid Igenia Buca to tell Lasinski that he had killed the boy with the last name, Silberstein. In the meantime, Leon was not safe despite the deal he made with Lasinski and Ingenia Buca.

Leon went to Werner with the news that Lasinski had to kill him. Verner wanted to save him and thus allowed Leon to stay in his apartment for the night. Leon was able to go home to his wife the next morning, who had not seen him since the morning before. Lasinski came to Leon’s house and told him that the ordeal was over. As payment, Leon made his wife give Lasinski linens. It was her job to sew linens from the cloth of Jewish families that was confiscated by Germans. Once again, Mr. Silberstein was in the position where his life had been spared.

Mr.Silberstein was able to conquer the pitfalls of being a yes-man to Nazis, by always defending his family, and using his power to save other Jews. One of the most apparent cases where Leon displayed unthinkable courage was in the perpetual defense of his nephew Sigmund, the younger brother of Jerzyk. The first time, he saved Sigmund’s life occurred when the ghetto was liquidated in May 1942.

When the ghetto was liquidated, Jewish social, cultural, and political activists were seized and killed. Thirty-nine thousand Jews were deported to the concentration camp, Treblinka in packed freight cars. Children and the elderly were often automatically killed and only two thousand Jews managed to escape or hide in the city.

Sigmund, who was only eleven at the time, was called to be deported along with his mother and Leon’s sister. Sigmund’s father and brother were considered able-bodied and thus allowed to remain in the city. The day on which Sigmund and the others were to be deported out of the bus depot in the centre of town, Leon’s sister spotted Leon working. A brave young woman, Leon’s sister walked into the area where Leon was working and demanded that the Ukrainian guards allow her to speak with him. Although the guards were furious, Leon spotted her and quickly pulled her in along with Sigmund and his mother. He took them to a hiding place where other workers were hiding their relatives. Remarkably, the three had been saved from the awful fate that lay only a couple hundred yards away.

Subsequently, Leon kept Sigmund and the others in a hiding place and eventually transported them into the small ghetto, which was the northeastern part of the ghetto. That section held some five thousand able-bodied Jews. Sigmund worked with the rest of the Jews Leon headed up and fell under the care of Leon and his wife when the rest of his family was eventually exterminated in concentration and labor camps.

Mr.Silberstein saved the lives of many others that bore no relation to him, other than the fact that they were Jewish. Once a girl asked Leon to bring her cousin to a boat that would take him to Germany. The boy had false papers to leave safely, but needed the assistance of Leon, who could travel the city freely. Leon thus manned a horse wagon and hid the girl and her cousin under hay in the back. They were able to get outside the ghetto unscathed, but once they arrived at the boat, the dock master demanded more money from the boy. Leon sensed that trouble would ensue and told the two that he would return them to the ghetto. While on the way from the boat, Leon was stopped by an official, who noticed the girl’s coat on top of the hay in the wagon. The official asked why Leon had such a nice coat and demanded that Leon abandon the wagon and let him drive it to the ghetto. Leon was able to convince the official that the coat meant nothing. Before returning to the ghetto, Leon deposited the coat and the boy’s false papers in a burnt-down house, and return the two safely. Once again, Mr. Silberstein had risked his reputation and life for others.

Mr.Silberstein’s ability to reason with the Germans assisted him in saving the lives of others. Mr.Silberstein once saved an entire family from the Nazis. The Rosencweig family had managed to hide underground in a shelter they built. The family consisted of many children and elderly persons, who would surely be deported to death camps or killed on the spot. Eventually they were found out and taken for investigation. Leon had known the family for years and was able to get the family pardoned by providing a service to a German official. The service was protecting the official from being killed by the Jewish Underground.

Mr.Silberstein’s name was well-regarded by this point and could work alone to save other Jews. At one point another selection occurred, but this time in the small ghetto, to weed out the “undesired”. The Jewish intelligentsia, which included professionals and academics were supposedly to be exchanged for German prisoners to go to Palestine. Leon however learned that no such exchange would take place and that the intelligentsia would in fact be taken to a cemetery and shot to death. Leon also learned that some friends that worked under his command were going to take part in the exchange. Leon rushed to the deportation site and picked out the people, thus saving their lives.

In the midst of this heroism, Mr.Silberstein had to participate in many dramatic and heart-wrenching experiences. The most significant was his participation in the murder of a Jewish traitor. For years, Mr.Silberstein has been hesitant to discuss this portion of his experiences. While he does not regret his actions, he has feared that such an act may be misinterpreted and reflect poor judgement on his part. As well, it is unthinkable that such betrayal occurred between Jews and Mr.Silberstein worries that others may doubt the validity of his story.

The Jewish ghetto eventually was separated into male and female living arrangements. Where the boys lived, a tunnel existed that went from the basement out of the ghetto. In the basement German clothes and arms were collected. One day, someone told the Germans that the tunnel and basement existed. As punishment, forty-three young boys were killed. The Jewish Underground asked Leon to find out who told the Germans the secret of the tunnel. Due to Leon’s connections with the German officials, he simply asked who revealed the secret. The Germans told him a man with the last name Rosenberg had tipped them off.

Rosenberg was a Jewish policeman, who patrolled the ghetto at night with other policeman. Leon knew that a traitor could leave the ghetto with no problem and he noticed that Rosenberg did. Leon was not fully convinced that Rosenberg was a traitor and did not want to act rashly. Leon asked a Sergeant in the Jewish Underground to let him know when Rosenberg was leaving the ghetto. When Rosenberg left the ghetto, Leon followed him to the train station with the Sergeant. Leon worked out an arrangement with the Sergeant where if he raised his hand that indicated Rosenberg was guilty.

Mr.Silberstein approached Rosenberg and saw in his attaché case the blue and white cap that Jewish policeman wore. Leon grabbed the hat and said to him, “You are a Jewish policeman who is not allowed to be alone. I have to take you to the ghetto to be shot.” At that moment, a German official overheard, kicked Leon in the spine and told him that the policeman was not his concern. When the German official came to the defense of Rosenberg, Leon knew that indeed he was a traitor. Leon then lifted his hand to the Sergeant.

Mr.Silberstein returned to the ghetto and calculated a plan with the Jewish Underground to murder Rosenberg. The Underground staged a fight and Rosenberg being a policeman came to break it up. The Underground grabbed him and took him to the basement where they forced him to reveal his crime. Afterwards, they gave him water with cyanide. He was buried in the basement.

Despite the severity of this story, Mr.Silberstein always made prudent judgements. This was the case in the closing of Mr. Silberstein’s life in the Holocaust.

Before the concentration camps and cities under German control were liberated in 1945 by the Russians, tens of thousands of people were killed in the final days that led up to the liberation. People often died on “death marches” that took place from camp to camp or in final acts of brutality by the Germans, who tried to cover evidence by exterminating remaining prisoners. The night before Częstochowa was liberated on June 16 1945, Leon got word that the Russians were coming. Leon knew that there would be danger. Already Sigmund was about to be deported to a labor camp with others. Luckily, Leon was able to take him out of the selection. That evening, Leon gathered a group of about a hundred and twenty people. On his authority and self-assurance, he led the group out of the camp around nine o’clock at night in freezing temperatures. They walked 3-4 hours in the direction of a Jewish cemetery in Auschliter where there was an air field. The circumstances were dangerous as German tanks were to the left and right of them. Eventually, people started complaining about the freezing temperatures. Leon turned the group around and by that point the Russians had begun liberating the city. Leon’s group were among the first Jews to be liberated. When the Russian army liberated Częstochowa, there were as few as 5,000 Jews in the area versus the 28,500 Jews that occupied the city when World War II began.

Mr.Silberstein’s nephew, Sigmund Rolat, compares this story to Moses leading the Jews of Egypt. This is a fine analogy to the courage and leadership Mr.Silberstein displayed when he took his own people and remaining family out of danger, risking his life. Despite Mr.Silberstein’s amazing fortitude, he could not save the life of his son. A tragedy which still looms large in his mind.

Mr.Silberstein and his wife had a son named Zygmuś prior to the war. Zygmuś was an incredible child. Advanced for his age, he read at the age of four. Like his dashing father, he was very handsome. Throughout the war, the Silbersteins were able to protect the child through Leon’s influence. However, towards the end of the war, they believed that they and their child would be killed eventually. Therefore, they left Zygmuś in the hands of a Polish doctor and his wife. When Leon would visit, he gave the doctor money and jewels in exchange for caring for Zygmuś.

After Częstochowa was liberated, Leon went to the doctor’s house to find Zygmuś but he was not there. For 6-8 weeks, Leon looked for him each day. With each passing day, he gave up hope. Finally, they found out that Zygmuś had been killed. A few days prior to liberation, Leon believed that he and his wife would surely be killed. He therefore gave the Polish doctor huge sums of money and jewellery including a three-karat diamond. Leon figured that if he and his wife died, their son would be better protected and at least live with a wealthy family. The doctor, however, in awaiting their death and believing he had received the majority of their wealth, did not feel he could expect any more money in the future. He had drowned Zygmuś in a river.

Leon and Rose

(2nd and 3rd from the left),

with friends, celebrating

Rose’s service as

Secretary of the

Częstochowa Relief Society

of New York- Brooklyn Branch

Mr.Silberstein continues to question his action to surrender the majority of his wealth too quickly in the end. He believes that this final donation prompted the doctor to kill Zygmus. Although Leon and his wife survived the war a large portion of their spirit had been destroyed, leaving permanent sadness in their heart and home.

It is terribly sad that Mr. Silberstein’s soul will never be at rest. He can never forget the pain and terror that he witnessed or go back on fateful decisions he made in the past. This is a great tragedy as Mr.Silberstein has exhibited more strength, courage, sensitivity, and love than anyone could in their lifetime. While he has lived his life serving others, he is too distraught and too modest to realize how he has acted as a great giver to humanity.

Leon Silberstein is nothing short of a hero.

Submitted by:

Leon’s son

Alan Silberstein.

It was written in 1995

by

Jill Tanen

a young college student.

Sadly, Leon passed away

a year later, just short

of his 92nd birthday.

This piece was published in

Ben Giladis

The Voice of Piotrków.

Edja Rosenzweig Darrow z"l

Edja Rosenzweig Darrow z"l

- a Story of Survival

Edja Rosenzweig Darrow was born in Częstochowa on 21st October 1921 into a warm and loving, family of eight children. Her very orthodox father was a skilled but very poor shoemaker and could not spare the money even for her to have a Zionist-club uniform. What he liked to do was sing. He was a cantor and a “Klezmer …. with a three-piece orchestra.”. At the age of 12, Edja left school to earn money for the family.