Sam Krycer z"l

Sam Krycer z"l

- Częstochowa-born centagenarian and Australian World War II veteran

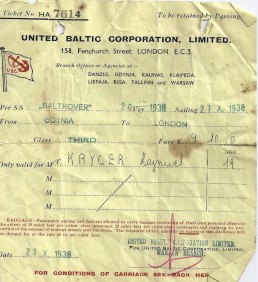

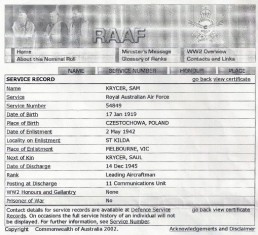

Sam (Zajnwel) Krycer z”l was born in Częstochowa on 17th January 1919. He arrived in Australia on 11th December 1938, settling in Melbourne. During World War II, he served in the Royal Australian Air Force.

Sam (Zajnwel) Krycer z”l was born in Częstochowa on 17th January 1919. He arrived in Australia on 11th December 1938, settling in Melbourne. During World War II, he served in the Royal Australian Air Force.

On 25th April 2019, at 100 years of age, he represented the Royal Australian Air Force and led the annual ANZAC Day parade (Australia’s memorial day).

Sadly, Sam passed away on 31st July 2019.

Between his participation in the parade and his passing, Sam agreed to talk about his life with our World Society webmaster, Andrew Rajcher.

Click HERE to read Sam describing his long, eventful life.

SAM AND HIS FAMILY

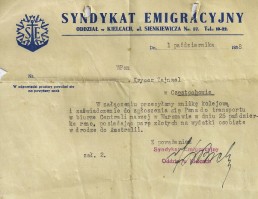

LEAVING CZĘSTOCHOWA FOR AUSTRALIA

MILITARY SERVICE IN WORLD WAR II

ANZAC DAY – 25th APRIL 2019 (Australia’s memorial day)

In 2019, Sam was given the honour of leading the annual march, from Melbourne’s downtown area to the city’s Shrine of Remembrance.

Webmaster’s Comment:

The pictures in this tribute page

have been supplied by Sam’s sons

David Krycer and Colin Krycer.

I thank them sincerely for arranging

my interview with their late father and

for supplying the pictures appearing here.

In May 2019, it was truly an honour

for me to sit with Sam, in his home,

and to listen to his eventful story.

Częstochowa's Israel Heroes

Częstochowa's Israel Heroes

- Honouring True Heroes

In this section of our website, we honour Israel’s “Częstochowa Heroes” – those Częstochowa landsleit who gave their lives in Israel’s Defence and/or Security Forces before, during and after the creation of the State of Israel.

In this section of our website, we honour Israel’s “Częstochowa Heroes” – those Częstochowa landsleit who gave their lives in Israel’s Defence and/or Security Forces before, during and after the creation of the State of Israel.

Many Polish Jews were involved in the campaign to establish a Jewish state in Israel. Some immigrated to Israel before World War Two. Some of those, prior to immigration, had fought World War Two battles in foreign armies or as Jewish Brigade volunteers. Most of them, Holocaust Survivors, who came from Europe illegally, immediately went to war for the independence of their new country .

The battles were fierce and some of those Czestochowa heroes, who had lived through the inferno in Europe, gave their new country, Eretz Israel, their most precious gift of all – their lives.

Through their sacrifices and deaths, they commanded us to live. We will remember them forever!

In composing our list, we draw upon the resources of Izkor, the commemoration website for the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces.

Below, we present the stories of these “Częstochowa Heroes”.

SIMPLY CLICK ON EACH NAME TO READ THEIR STORIES OF HEROISM.

The son of Shmuel-Yakovand Devora, he was born in Częstochowa in 1922. In his youth, with his parents, he immigrated. Dov completed his schooling in Paris and began work as a salesman in a store. He was a member of a Zionist youth movement and dreamt of immigrating to Eretz Yisrael. However, in 1940, he found himself caught up in the fate of European Jewry. Dov was taken to a forced-labour camp where luck and his youthful strength helped him to survive five years of slavery and hard labour. When was liberated, he actively devoted himself to Zionism and to preparation for his immigration to Israel.

He left his parents behind in the Diaspora and, in November 1946, he set sail for Mandate of Palestine on the ship “Latrun” as an illegal immigrant. The ship was intercepted by the British and its passengers were sent to a camp in Cyprus. After four months, he was freed and arrived in Israel. He immediately joined the “Notrut” (the Jewish guard brigade in the British police force during the British Mandate period) and the “Haganah”. Following this he joined the IDF and served in the Kiryati Brigade.

Dov fell in the battle of Dayr Tarif, during Operation Danny on 12th July 1948 (5th Tammuz 5708). He was interred in the Military Cemetery of Nachalat Yitzchak in Tel-Aviv.

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

The son of Mosze and Pnina, he was norn in 1929 (5689) in Częstochowa. In 1936, (5676), the family immigrated to Mandatory Palestine and settled in Tel-Aviv, where Yitzchak attended the “Nes Tziona” Elementary School. When he grew up, and understood the degree to which his parents were struggling to support their two children, he began to give up playing games in order to help his mother with the household chores. He was also active in the “Machanot Ha’Olim” youth movement and later in the “Ha’Tenua Ha’Meuchedet” youth movement. Upon completion of his primary school studies, he began work in an auto repair garage and he bring his wages home to his parents.

He was accepted to the Haganah and began his Army service as a signaller. Upon completion of his course, he continued on as a “madrich” in Gadna, a program to prepare young people for the Army. Together with his friends, he went out for “hachshara” (training) at Kibbutz Cholta, because he saw his future on a kibbutz. He assisted in training and worked with dedication and responsibility. He was placed in charge of the work schedule in the “Garin” (a group of candidates to be accepted into the kibbutz).

In the winter of 1948, he fought in the Upper Galilee as part of the “Ha’Galil” Battalion of the Palmach, which later became one of the battalions of the Yiftach Brigade. He was seriously wounded in a retaliation operation against the village of Ichsanya on 3rd March 1948 (2nd Adar Sheni 5708). Yitzchak demanded that his comrades leave him he was already mortally wounded – and there he died. Yitzchak was interred in the Chulta Cemetery.

Just prior to his death, he told his comrades, “We will emerge victorious. There is no other way. We will finish the War in victory”.

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

The son of Dov and Arella, he was born in Częstochowa on 21st February 1932 (14th Adar Aleph 5692). In 1934, he immigrated to Mandatory Palestine, completing his studies at the “Chugim” High School in Haifa.

In October 1950, he joined the IDF in October 1950 and served in the Nachal Brigade. However, because he was not satisfied with what he was doing there, he volunteered to transfer to the Air Force, where he successfully completed pilot training with the rank of Second Lieutenant, after which time he competed a second course.

His commanders praised him greatly as a disciplined and responsible pilot. He fell while carrying out his duties on 14th December 1952 (26th Kislev 5713) and was interred in the Haifa Military Cemetery. He was posthumously promoted to the rank of Lieutenant.

In 1955, his parents made a donation to the aeronautical library at the Technion University and, on the shelves, a memorial plaque was mounted bearing the inscription “Tvi’s Corner”.

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

The son of Mosze and Róża, he was born in Częstochowa in October 1917 (Cheshvan 5678). He immigrated to Israel in 1927 and, there, completed his studies in elementary school. He then rounded out his education through self-study. By profession, he was a weaver by profession. In 1948, hoined the IDF and fell in the performance of his duties on 28th May 1952 (4th Sivan 5712).

He was interred in the Kiryat Shaul Military Cemetery in Tel-Aviv. He was survived by his wife and three children.

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

The son of Dawid and Lea, he was born in Częstochowa on 10th July 1948 (3rd Tammuz 5708). The family immigrated to Israel in 1950. He attended the Be’eri elementary school in Neve She’anan, Haifa and then high school at Tichon Ironi Gimel.

He belonged to the “Ha’Tnuah Ha’Meuchedet” youth movement. He successfully completed a course for “madrichim” (counsellors) in Kibbutz Ramat Yochanan and was very successful as a “madrich”. He played soccer in the “Hapoel” movement and was also active in a course for junior level “madrichim” and heads of basketball teams. He regularly swam across the Kinneret and took part in various races. He was a member of the “Ha’Noar Le’Nnoar” movement and, there, he met with youth who had turned to crime. This was Moshe’s attempt to understand their way of life and to influence them to change their lifestyle to a more positive direction. He collected stamps and coins and travelled all across the country.

Upon beginning high school, he settled quite well and was prominent in the student body, but that did not prevent him from engaging in naughty behaviour and in pranks. But, as time went by, they got to know him better and to see that, behind the regular exterior, there was a lad with unusual characteristics. These were prominent whenever he was confronted with a challenge which stimulated him to make an effort which demanded of him to utilizs his skills.

He was an exemplary commander during the Gadna travels. He showed initiative in organization and in providing assistance where needed, especially in times of crisis when difficulties were encountered. In these cases, he would act with maturity and responsibility and he could be counted upon. His personality radiated confidence and calm over his surroundings and, in the classroom, he related, seriously, to those subjects which interested him. There would be a true connection between him and the subject and also between him and his teacher. A feeling of responsibility in him was prominent, when he was required to calm the class, to restore quiet in the classroom and after some act of naughtiness. Menashe was the one who would turn to the chevra and say, “Okay, enough now”.

It is no wonder that, later, Menashe found his place in the army, in the Tzanchanim (Paratrooper) Corps. Even though he was his parents’ only son, and all the family had perished in the Holocaust, Menashe succeeded in getting what he wanted within the Tzanchanim. He fought in the Six-Day War in the Sinai and on the Golan Heights. At the end of the battles, he completed a Class Commander course and an Officers Training course. He joined the “sayeret” and, in the “hot” period of terroristism in the Jordan Valley and on the West Bank, he participated in many difficult and cruel pursuits, during which the best of the Tzanchanim commanders fell, such as Arik Regev, Gad Manala, Moshe Stempel and others.

His soldiers respected him because of the way he related to them and how he served as a personal example. He demanded obedience from them, but through recognition. He demonstrated friendship and loyalty from them and, through his pleasant manner, he realised his goals. He preferred to explain and to persuade in a sociable kind of way and, in this manner, he was able to find a way to those soldiers who were problematic and turn them into dedicated and loyal soldiers. During his period of service, he attained the rank of Lieutenant.

On 26th October 1968 (4th Cheshvan 5729), as he was leading his soldiers to take cover during a period of intense shelling, he fell in a battle near the Suez Canal. He was interred in the Haifa Military Cemetery. In a letter of condolence to his parents, his commander wrote, amongst other things,

I knew him well. I saw him perform in training and in operations. He was an excellent officer, understood his job and mastered his men and material. He belongs to that generation of giants who arose from the fire of the Holocaust. I am sure that his immediate surroundings influenced him more than anything – his home and his parents. He was close to his family and wanted them to be well. He understood that, given the conditions we are faced with in this country, someone has to do the hard work and he was not willing for someone else to do that work for him. I am sure that all that Menashe did, he did forothers. We are obligated to continue where Menshe left off – we and you.

On Chanukah 5729, the Student Council of the Ironi Gimel High School of Haifa published a booklet entitled Hadim, in which there are pages dedicated to the memory of Menashe. About a year after Menashe fell, a book entitled I Have an Only Son, G-d Guard Him, written by Binyamin Zev Yefet, was published by Moked Publishers His grave lies in the Haifa Military Cemetery.

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

The son of Shimon and Esther, he was born on 14th February 1914 in Częstochowa. He was the great-grandson and grandson of a family of rabbis. In his hometown, Marian attended yeshiva and high school. During his studies, he belonged to the Betar youth movement. After graduating from his studies, he moved Łódź, where he was a merchant. He married and was the father of three daughters.

At the outbreak of World War Two, he was drafted into the Polish army and, in battles near Warsaw, he was captured by the Germans captivity. The Germans did not realise that he was Jewish and, at the end of 1939, together with other Polish officers, he succeeded in escaping captivity. He then reunited with his family and moved to the Soviet Union. After wandering all over the Soviet Union, they reached Uzbekistan. When a Polish army was established in the Soviet Union, under the command of General Anders, Marian joined and, with the Anders army, he went through Iran, Israel (where his family stayed) to South Africa. From there, he moved to England and took part in the invasion of Normandy, liberating Europe from the Germans.

On a journey of blood and fire, he passed through France, Belgium and the Netherlands and, with his unit, arrived in Germany. On 14th May 1945 (2nd Sivan 5765), he was killed by a landmine near the city of Wilhelmshaven and was interred in a mass grave with his comrades-in-arms. He left a wife and three daughters. The rest of his family perished in the Holocaust.

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

The son of Mosze and Lea, he was born in Częstochowa on 23rd November 1913 (23rd Cheshvan 5674). As a teenager, he dropped out of school in order to help support his family. He worked alongside his father in a lock manufacturing factory. He persevered in increasing both his productivity and the quality of his work and, eventually, rose to the position of foreman and co-ordinator in the department which assembled the locks.

He joined the Ha’Shomer Ha’Tzair youth movement and was known both for his reticence and for his activity. He tended to rise above difficult positions, but disliked talkativeness. David was sent for “hachshara” (training) in Chełm and Lublin and served as work organizer and Assictant Treasurer, responsible for the financial support of his forty movement members from the proceeds of their work in various places. In this capacity, he also looked for employment opportunities for them and sometimes only two of the forty were working. He, therefore, needed to find opportunities to find sources for loans.

When it came his turn to immigrate to Eretz Yisrael, he gave up his right in an act of sacrifice, giving his money to one of his brothers in order to allow him to immigrate, so as to allow him to avoid served in the Polish Army. David, himself, was conscripted into the Polish army at the beginning of World War Two. After Poland capitulated to the Germans, David succeeded in avoiding German imprisonment and continued to work in the Częstochowa factory. He continued working while being confined in Częstochowa’s “Big Ghetto” and, after most of the Jews were killed, also in the “Small Ghetto”.

At the same time, he was active in the ghtteo underground, specialising in the digging of bunkers and communication tunnels. With his comrades, he endured the efforts of communicating with the Socialist Polish Underground outside of the ghetto, in order to obtain guns and help. However, from the Poles, they were unsucessful, encountering an aggressive response. When the “Small Ghetto” was liquidated, David succeeded in fleeing alone and, with the help of a Polish friend, found his way into the forest. The Polish Partisans refused to accept Jews into their ranks. So, for more than a year, he and a few Jewish comrades lived with a Jewish Partisan group, surrounded by danger from the Germans on the one hand and hostility from the Poles on the other. After he was liberated, he fell ill from exhaustion and from the hardship.

When he recovered, he went to Romania. There he dedicated himself to the service of the “Bricha” (the organised underground effort which helped Jewish Holocaust survivors escape post-World War Two Europe to Mandatory Palestine in violation of the British White Paper of 1939). In this capacity, they assisted many to reach Italy in order to immigrate, from there, to Eretz Yisrael. During this time, he received a certificate which allowed him to be able to immigrate legally to Mandatory Palestine, but he relinquished it and, for two years, worked on the Polish-Austria and Germany-Italy routes, in order to facilitate the escape of Jews to sea ports for illegal immigration.

In August 1946, he was able to illegally immigrate to Israel, together with his brother. There, he joined his friends on Kibbutz Yad Mordecai. In spite of his frail body, due to hhis past great suffering and exertion, he immediately went to work and tried to do even more than he was capable of doing – as was always his way. But remained a loner and distanced himself from his contemporaries, spending his spare hours in reading or in recalling grim memories.

In the winter of 1948, when the War of independence broke out, he volunteered his services in the planning of the trenches and bunkers, a specialty culled from his past experience in the Częstochowa ghetto. When his advice went unheeded, he would sit silently, carrying out his responsibilities to guard, to dig and to stand guard at the observation posts. During the campaign against the Egyptians, he also undertook the responsibilities of those who had fallen. He would stand at observation points without being relieved and without any complaint – 19th May 1948 (10th Iyar 5708), he was hit by a bullet and died.

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

The son of Avraham and Róza, he was born on 31st December 1912 (21st Tevet 5673) in Częstochowa. When he was a pupil in the local high school, the “Ha’Shomer Ha”Tzair” youth movement, where he was known for his mild manner, his energy, his perseverance, his intelligence and for his devotion to the ideal. He soon became prominent as a madrich (counsellor) in the local ken, in summer camps and, later, as a madrich in the Zagłembie region of Poland. He later joined the primary leadership of the movement in Równo and then in the movement’s centre in Warsaw.

On 4th April 1939, he immigrated to Mandatory Palestine and joined the first encampment of his kibbutz in Netanya. Through sheer determination, he overcame the pains of rheumatism from which he suffered and became accustomed to hard, physical work. Evenings and Shabbatot were spent in cultural programming in his kibbutz and in involving himself in the affairs of the community of workers in Netanya.

In 1942, he joined the British Army and served in the Artillery Corps in the Western Desert of North Africa, as well as in Italy. In the Army, also, he dedicated himself to public activities and was chosen as a representative to mutual assistance organisations.

Upon his return to his home in Kibbutz Yad Mordecai in the Gaza plain, he was chosen as the Kibbutz Secretary, a position which he fulfilled with dedication. Later, he became a member of the “Ha’Merkaz Lagola” (The Diaspora Center) in which he was a madrich for the Cherut garin of new immigrants from the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. He helped them to settle, practically and emotionally, into work and life on the kibbutz in Israel. In addition to his various public positions, he also worked in the chicken-coop of the kibbutz.

As a veteran soldier, he did not believe that Yad Mordecai could withstand an assault from the neighbouring Egyptian Army, which was vastly better equipped, but he still contributed his share to the defence of the kibbutz. As a trained artillery soldier, he utilised the only mortar in their possession, carrying it with him from one positon to another and striking at enemy concentrations. When the shells ran out, he continued to fight as a rifleman on the front line.

He wrote a letter to his wife on his last day, when she and their two children – together with the rest of the mothers and children – had been evacuated from the kibbutz. In it, he expressed the hope that “perhaps some of our kibbutz members will still successfully see victory and will take part in the restoration of the ruins”. Further, he writes, “We hope to see each other again. But, if not, I hope that you will know how to bear up under this as well”. To his son he writes, “Here, that there are dozens of thousands of shells”.

On 23rd May 1948 (14th Iyar 5708), the armoured divisions of the enemy broke through and he fell, while still standing on watch. He was interred in the Yad Mordecai Cemetery (Military Section).

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

The son of Margalit (Perłą) and Kalman, he was born on 11th February 1929 (1st Adar Aleph 5689) in Częstochowa, Poland, to parents who were observant Jews. When he was three-years-old, the family settled in the Free City of Danzig and Zvi attended a local, Jewish, elementary school. In 1939, Zvi and his father sailed to Mandatory Palestine on the illegal immigrant ship, the “Astir”. (His mother and sister remained behind, for fear of danger, in order to immigrate to Eretz Yisrael at a later date. Sadly, they did not immigrate in time and perished in the Holocaust). The ship was intercepted by the British and sent back out to sea. After much tribulation, Zvi succeeded in landing on the Gaza coast on a Greek fishing vessel, the “Mardas”.

Zvi underwent a short period of Youth Aliyah “Hachshara” (training) in Kiryat Chaim. From there, he moved to the Menachamia moshav, where he attended school for about two years. Afterwards, he continued his studies in the Ben-Shemen Youth Village. Zvi-Moshe excelled in his studies and was one of the pillars of the student body. He left Ben-Shemen as a member of the youth movement “Ha’Noar Ha’Oved”, in order to participate in the “Hachshara” at Kvutzat Geva. During the period of his service in the Palmach, he was known as a dedicated and courageous individual and was considered as a superb sapper.

On 14th February 1948 (4th Adar Aleph 5708), Zvi set out together with another combatant [Amikam Alon], who drove a vehicle which was loaded with explosives, in order to blow up the Sheikh-Hussein Bridge, on the Jordan River, next to the town of Beit Shean. The driver was supposed to break through the barrier and drive onto the bridge. Zvi, as sapper, was to be prepared to detonate the explosives. Despite the heavy fire which was coming from the Jordan Legion guard, the driver succeeded in getting the vehicle onto the bridge and then jumping into the Jordan River, where he was rescued. Zvi detonated the explosives, but was killed during the operation. He was interred in the cemetery in Kibbutz Ein Harod. He is memorialised in a booklet, produced in memory of the members of Kvutzat Hachoshlim [a kibbutz located in the Eastern Galilee, which is today called Amiad].

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

The son of Faybisz and Ida, he was born in Częstochowa on 5th August 1920 (21st Av 5680). All members his nuclear family, except for his brother Avraham, perished in the Holocaust. Following the Second World War, Zalman was hospitalised in the St. Ottilien DP Hospital next to the Dachau concentration camp. From there, he was released on 29th April 1945.

On 19th October 1946, he set out for Palestine from the port of La Sete in France, as one of the illegal immigrants on the ship, the “Latrun”. However, the British intercepted the ship on 1st November 1946, preventing its passengers from landing on the shores of Israel and deporting them to a detention camp in Cyprus. On 15th August 1947, he was freed from detention in Cyprus and arrived in Haifa. He was then sent to the Rishon Lezion Workers Council. He resided in immigrant housing and was employed, as a foreman, by one of the local citrus growers. In November 1947, Zalman met up with two cousins, who had survived the Holocaust -, Yisrael Stowitski and Hersz-Lejb Rozenfeld. However, after this, contact was broken. As far as can be determined, until Zalman was killed, he did not have any contact with any other family members.

At the beginning of July 1948 – during the first cease-fire in the War of Independence – Zalman, together with about four hundred other citizens who resided in settlements in the area, were recruited for work in building fortifications on the “Southern Front”. Zalman and his comrades worked under the command of the 53rd Battalion of the Givati Brigade which was active in the region. This supporting military activity and the assistance to the fighting units was called Betzer and was a joint project of the Haganah and the General Workers Union. This framework employed thousands of workers, who were not fit for fighting roles. Instead, they were involved in the construction of fortifications, in the digging of bunkers and in the building of protective walls.

According to available information, Zalman Rozenfeld was recruited for this project and was killed, by Egyptian gunfire from Beit Daras, on 8th July 1948 (1st Tammuz 5708). Apparently, he was in the settlement of Be’er Tuvia. In 1951, his brother Avraham immigrated to Israel and attempted to locate his brother. The Jewish Agency’s Department for Searching for the Missing was unsuccessful in locating him. Sadly, the fact was that Zalman was no longer amongst the living. His brother Avraham died in 1984, never knowing what happened to Zalman since they were separated in Europe.

At the end of the 1990’s, during the course of an investigation carried out by the “Eitan” Unit in the IDF, for locating soldiers missing in action, documents were found which led to a renewed research to find out what happened to Zalman. In 2009, Zalman was declared by the IDF and the Israeli Defense Ministry to be a fallen soldier, whose place of burial is unknown. The circumstances surrounding his death remain a mystery and the issue is still under investigation.

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

The son of Mosze-Ze’ew and Rachel, he was born in Częstochowa in 1924. Raised in an ultra-Orthodox home, he studied in elementary school and in yeshiva. With the onset of World War Two, he was uprooted from his surroundings. He was confined in detention and labour camps and labour thoughout the Nazi occupied, suffering a great deal until being liberated by the Allied forces . He found himself in the Bergen-Belsen DP camp, where he joined the Haganah and prepared for immigration to Palestine to where he immigrated in 1947.

In Israel, he worked as an auto-mechanic in a garage in Tel-Aviv. In addition, he participated in the activities of the Haganah. He successfully completed a course in first-aid through Magen David Adom and, with the worsening of conditions near the borders of Tel-Aviv, he would go out to positions as an Army medic. Ober the course of his activity, he fell at his position, during the city’s bombardment, at Rechov Ha’Tabor in Tel-Aviv 21st March 1948 (10th Adar Sheni 5708).

He was interred in the military cemetery in Nachalat Yitzchak, Tel-Aviv.

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

Israel Wollhendler was born in 1913 (5673) in Czestochowa. At the age of eight, he joined the “Young Cubs Regiment” of Ha’Shomer Ha’Ttzair and remained active within this Zionist youth movement until 1925, when he immigrated, with his family, to Eretz Yisrael/Mandatory Palestine.

In Israel, he learned to drive, something which remained as his occupation. His interest in sport culminated in his joining the Maccabi organization. At first, he participated in soccer, later athletics and then became a champion weightlifter. Yet he was also a nature-lover and frequently wander through the Carmel Mountains, which he got to know quite well.

In the Arab uprisings of 1929, he acted as a Haganah liaison between the settlement of Mishmar Ha’Yarden and Haifa and also performed guard duty in the Mt. Carmel area. In the Arab uprisings of August 1936, he volunteered for guard duty and excelled in his courage, dedication and readiness to carry out his job no matter what the danger.

In 1937, he began work with the “Hovala” Freight Group and was active in the National Transport Workers Association. On 15th August 1938, as he was driving a car on its way from Achuza in the Mt. Carmel area to his home, he was attacked by an Arab gang and was shot and killed on the spot. He was survived by a wife and daughter.

Click HERE to read his story in Hebrew.

(Courtesy: Izkor – commemorating the fallen personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces)

From the Webmaster:

My sincere thanks to Alon Goldman,

whose idea it was to create this memorial page and who did much of the original research which it contains.

The information contained here is based on

– a website dedicated to the personnel of Israel’s Defence and Security Forces

who fell during the creation and/or defence of the State of Israel.

Interesting Videos

Interesting Videos

“AS IF IT WERE YESTERDAY”

In this film, “As If It Were Yesterday”, created in 2004, Sigmund Rolat tells of his pre-War life in Częstochowa and of his wartime experiences as a child in the Częstochowa ghetto and in the HASAG-Pelcery slave labour camp.

He also describes returning to Częstochowa, many years after the War, when he located the grave of his brother, Jerzy, a partisan who was executed by the Nazis at the Częstochowa Jewish Cemetery..

The World Society of Częstochowa Jews & Their Descendants gratefully thanks TV Orion in Częstochowa and, in particular, its Director Cezary Szymański, for helping to make this video accessible on our website.

“GENERATIONS OF THE SHOAH – THE SIGMUND A. ROLAT STORY”

This film, “Generations of the Shoah – the Sigmund A Rolat Story” is a longer version of that which was shown during the celebrations of Sigmund’s barmitzvah, a Jewish lifecycle event which he shared with Henry, his thirteen-year-old grandson.

The World Society of Częstochowa Jews & Their Descendants gratefully thanks Sharon Danzger and her sons Adam, Ben and Daniel, for permission to feature this film on our website.

“THE RETURN OF THE VIOLIN”

Violinist Bronisław Huberman was a Częstochowa Jew who became famous as a child-prodigy.

He owned a rare Stradivarius which, during one of his concert tours, was stolen. For many years, the violin’s fate remained unknown – that was until another world-famous violinist, Joshua Bell, discovered it and, since that time, has played the instrument in all his concerts.

During our World Society’s Third Reunion, in October 2009, the Huberman Stradivarius returned home to Częstochowa, when Joshua Bell gave a concert in the Częstochowa Philharmonic Hall, the site of the New Synagogue which was destroyed during World War II.

With the imminient Nazi threat, Huberman rescued many European Jewish musicians who then, together, formed the Palestine Symphony Orchestra which, today, is known as the Israeli Philharmonic Orchestra.

This is the story of how that instrument returned home to Częstochowa.

“THE JEWS OF CZĘSTOCHOWA” EXHIBITION

The exhibition was originally created for the World Society’s First Reunion, which took place in Częstochowa in April 2004.

Since then, it has travelled the world but, until 2016, it did not have a permanent home.

Finally in 2016, thanks to the Częstochowa Mayor and City Council, it found a permanent home as the Jewish Museum of Częstochowa, located at ul Katedralna 8, in the city’s former Jewish district.

(This building is also home to the Częstochowa branch of the Jewish Social-Cultural Association – the TSKŻ.)

More information about the Jewish Museum can be found HERE.

“THE JEWISH HISTORY OF CZĘSTOCHOWA”

An excellent, English language presentation of both the city and its Jewish history and heritage.

“CZĘSTOCHOWA 1939-1945 – WORLD WAR II”

An excellent documentary telling the story of Częstochowa during World War II.

(In Polish with English subtitles)

A WALK AROUND THE HASAG-PELCERY SLAVE LABOUR CAMP

Filmmaker Marcin Bocian walks around the site of the former HASAG-Pelcery slave labour camp in Częstochowa.

This camp operated as an munitions factory for the German Hugo Schneider Aktiengesellschaft-Metalwarenfabrik company of Leipzig.

It was also where many surviving Częstochowa Jews struggled to see the war’s end and liberation on 16th January 1945.

(English language)

FLYING OVER THE HASAG-PELCERY SLAVE LABOUR CAMP

Kamil Langier, of the Stowarzyszenie Historyczne Reduta Częstochowa, uses a video drone to fly over the site of the former HASAG-Pelcery slave labour camp in Częstochowa.

This camp operated as an munitions factory for the German Hugo Schneider Aktiengesellschaft-Metalwarenfabrik company of Leipzig.

It was also where many surviving Częstochowa Jews struggled to see the war’s end and liberation on 16th January 1945.

(English language)

THE OLD SYNAGOGUE AND THE JEWISH HOSPITAL

Filmmaker Marcin Bocian walks through Częstochowa’s Old Town, visiting the site where the Old Synagogue once stood.

He then visits the hospital which was established by Częstochowa Jews at the beginning of the 1900s.

(English language)

ULICA STRAŻACKA – THE SITE OF “BLOODY MONDAY”

Filmmaker Marcin Bocian walks along ul. Strazacka, the site the murderous “Bloody Monday, which took place on 4th September 1939.

As he walks, he compares the present surroundings with pictures from the time of the massacre.

(English language)

THE SITES OF THE “BIG GHETTO” AND “SMALL GHETTO”

Filmmaker Marcin Bocian drives through the area which once constituted the areas of the “Big Ghetto” and the “Small Ghetto”.

He begins at the Częstochowa Umschlagplatz monument, then along ul. Nadrzeczna, the Stary Rynek, ul. Kozia and ul. Spadek. On ul. Garibaldiego, we see the site of the mikveh and the Philharmonic, which was built on the remains of the New Synagogue.

(English language)

“THE GHETTOS IN CZĘSTOCHOWA”

This is a lecture by Wiesław Paszkowski of the Częstochowa Museum’s Centre for the Documentation of the History of Częstochowa.

Recorded on 18th November 2021, it was held to mark the 80th anniversary of the establishment of the “Big Ghetto” in Częstochowa.

The event was organised by the Częstochowa branch of the Social-Cultural Association of Jews in Poland (TSKŻ) and was held in the branch’s rooms above the Częstochowa Jewish Museum.

The video recording of the lecture is courtesy of Częstochowa’s Orion TV..

(Polish language)

THE CZĘSTOCHOWA “SMALL GHETTO”

Filmmaker Marcin Bocian takes us to ul. Kozia and plac Obrańców Getta (Ghetto Defenders Square) which, before the war, was named plac Warszawsski.

He relates some stories about the place, showing the remains of the buildings and the memorial plaque honouring the Jews who perished there..

(English language)

“A LOVE STORY”

This documentary tells of the love between Bogdan Jastrzębski and Krystyna Geisler and an act of rescue for which Bogdan and his mother were honoured with the title of “Righteous Among the Nations”

(Polish, with English subtitles)

RABBI MEIR LAU – CZĘSTOCHOWA UMSCHLAGPLATZ MONUMENT DEDICATION

The Częstochowa Umschlagplatz Monument, created by our dear landsmann Samuel Willenberg z”l, was dedicated during the World Society’s Third Reunion in October 2009.

During the monument dedication ceremony, former Chief Rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Meir Lau, a former inmate of HASAG-Pelcery, gave this address.

“WHERE DID THE CZĘSTOCHOWA JEWS GO?”

The first post-war visit to Częstochowa by Samuel Willenberg z”l.

(In Hebrew with Polish subtitles)

“I WAS LUCKY”

The memoirs of Elżbieta Mundlak Zborowska – granddaughter of Częstochowa Chief Rabbi Nahum Asz z”l.

(Polish with English subtitles)

“REMEMBERING CZĘSTOCHOWA”

Seven Jewish Holocaust survivors from Częstochowa recall their experiences.

(English language)

“TO JEDNAK JA ZWYCIĘŻYŁAM” (“But, Somehow, I Won”)

Irit Amiel z”l, Israeli poet, writer and translator, was born in Częstochowa in 1931 as Irena Librowicz, tells her story.

This video was recorded on 26th-27th May 2014, when she visited Częstochowa.

(Polish language)

OTHER VIDEOS OF INTEREST

- “Treblinka’s Last Witness” – Samuel Willenberg – Polish & English/English subtitles

- “Made by Żyd” – Hebrew/English subtitles

- “Made by Żyd” – Hebrew/Hebrew subtitles

Memorial Monuments Worldwide

Memorial Monuments to Częstochowa Jewry

- monuments erected in places around the world in memory of our martyrs

CZĘSTOCHOWA, POLAND

During World War II, the Warta Railway Station was located on this site on ul. Strażacka in Częstochowa. It was from here that, between 22nd September and 7th October 1942, the Germans sent 40,000 mostly Częstochowa Jews to their deaths at Treblinka.

The monument, made possible through the financial support of World Society President Sigmund Rolat, was unveiled on 20th October 2009 during the Third Reunion of the World Society of Częstochowa Jews & Their Descendants

It was created by Częstochowa landsmann and Treblinka escapee Samuel Willenberg z”l. The crack in the wall represents the Holocaust of Częstochowa Jewry with, to the right, real railway tracks representing the road to Treblinka. The Magen David on the left represents the fact that the Jewish people live on.

Directly in front of the monument (top pic) stands a transparent pillar containing the schedule of the trains heading to the Treblinka death camp. Adjacent to the monument (bottom pic) stands what is left of the Warta Railway Station building from where the trains departed.

TREBLINKA, POLAND

The Treblinka death camp is to where, during the Holocaust, most Częstochowa Jews were transported and where they perished. Today, the site also contains a symbolic cemetery containing around 17,000 memorial stones, representing the places from where the victims came. The stone size varies according to the estimated number from each place.

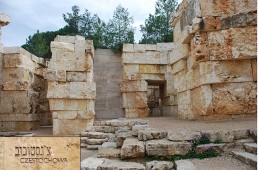

YAD VASHEM, JERUSALEM, ISRAEL

The Valley of the Communities in Yad Vashem is a massive 2.5 acre monument excavated from the natural bedrock. Its stone walls are engraved with over 5,000 names of communities. Each name recalls a Jewish community which existed for hundreds of years. For their inhabitants, each community constituted an entire world. Today, in most cases, nothing remains but the name.

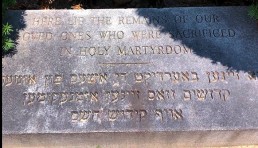

CHAMBER OF THE HOLOCAUST, JERUSALEM, ISRAEL

Located on Mount Zion, this memorial was inaugurated on 30th December 1949 by the Ministry of Religion.

The museum features a large courtyard and ten exhibition rooms. The walls of the courtyard, plus several rooms and passages, are covered with tombstone-like plaques, inscribed in Hebrew, Yiddish and English, memorialising more than 2,000 Jewish communities destroyed during the Holocaust.

The plaque commemorating Częstochowa Jewry is shown bottom-left.

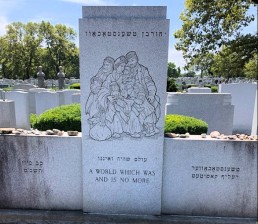

TEL AVIV, ISRAEL

This monument is located in the Nahalat Yitzhak Cemetery in the Givatayim district, just east of central Tel Aviv. The cemetery is officially “closed” although burials sometimes still take place for deceased who had pre-purchased their plots. As well as this monument to our Częstochowa Jewish martyrs, it also contains monuments to other “vanished Jewish communities”.

(More information requested: When was this monument erected and by whom?)

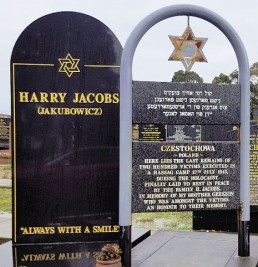

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

In the early 1980’s, Częstochowa Holocaust survivor Harry Jacobs (Jakubowicz) z”l and his daughter, Sylvia Horiniak (nee Jacobs), visited the Częstochowa Jewish Cemetery where they came across unburied human remains (bones). Harry committed himself to having these bones collected, shipped to Melbourne and, there, be given a proper and dignified Jewish burial.

Today, they rest in the Chevra Kadisha Jewish Cemetery in the Melbourne suburb of Springvale. While, to this day, their names are not known, they lie with dignity and under a matzevah which preserves their collective memory.

When Harry passed away in 1999, he was buried next the grave which, through his efforts, will remain a perpetual memorial to those who perished.

ELMONT, NY, U.S.A.

This monument is located in the Beth David Cemetery (Section B, Block 10) in Elmont, Queens (just outside of New York City). It was established by the Czenstochauer Bruder Verein (Częstochowa Relief Committee) and was dedicated on 8th June 1969.

The monument contains the ashes of victims from both the Auschwitz and Treblinka Nazi death camps.

The bottom photograph is of a plaque located on the lower part of the monument’s front side.

CHICAGO, IL, U.S.A.

This monument is located in the Waldheim Jewish Cemetery in the Chicago suburb of Forest Park. It was established in 1952 by the Chenstochower Society of Chicago.

(We have been informed that, while there are landsleit in Chicago, the Chenstochower Society of Chicago is, sadly, no longer active.)

TORONTO, CANADA

This monument is located in the Chenstochover Aid Society section of the Bathurst Lawn Memorial Park Jewish cemetery.

As shown on the reverse side of this monument (bottom pic), it was erected by the Society and was dedicated on 29th October 1978.

The archway seems to have been added later and dedicated in September 1992.

It bears the names of Częstochowa landsleit who perished during the Holocaust.

MONTREAL, CANADA

Inscribed in Hebrew, Yiddish, English and French, this monument (top left) is located in the Baron de Hirsch Jewish cemetery (Section A1, Road C) in the Côte-des-Neiges neighbourhood of Montreal. It was erected in 1966 by the Chenstochower Society of Montreal. The reverse of the monument bears the names of Częstochowa Holocaust martyrs.

In front of this memorial is a matzevah (bottom left) marking the grave of a coffin containing the ashes of Treblinka victims.

(More information requested: Is the Czenstochower Society of Montreal still active?)

PARIS, FRANCE

Inscribed in both Yiddish and French, this monument is located in the large Jewish section of the Bagneux Cemetery, just outside of central Paris.

The left-hand panel lists the surnames of Holocaust victims from Częochowa and the surrounding area. The central and right-hand panels bear the names and, in many cases, photographs of Holocaust survivors who have since passed away.

(More information requested: Who erected this monument and when? Is there a photograph of the monument’s reverse side? Who is buried in the two graves at the foot of the monument??)

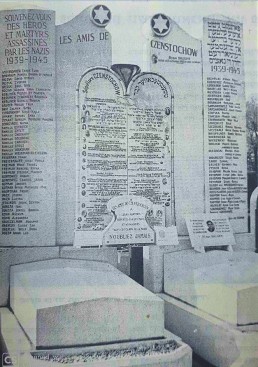

PARIS, FRANCE

This monument (pic left) is in Paris, erected by the “Friends of Częstochowa” . However, we know very little else about it.

(More information requested: Was this monument REPLACED by the monument above (colour photo) or does it still exist? When was this monument erected? Is there a photograph of the monument’s reverse side? Who is buried in the two graves at the foot of the monument??)

From the Webmaster:

My sincere thanks to

ALON GOLDMAN

for the idea for this page

and for much of the material

which appears on it.

If anyone is aware of

other memorial monuments,

anywhere in the world,

which are dedicated to

the memory of our

Częstochowa Jewish martyrs,

then please send me

a photograph, together

with a few words about it,

for inclusion on this page.

The Częstochowa Righteous

The Częstochowa Righteous

- Honouring True Heroes

In this section of our website, we honour the “Częstochowa Righteous” – people, who risked their lives and the lives of their families, to extend help to Jews during World War II. These individuals are true heroes and, just as we endeavour to preserve the memory of those who either perished or survived during the Holocaust, we also have an obligation to preserve the memory of those who came to the aid of Jews in those dangerous times.

This listing will not only include those who performed such acts of heroism within Częstochowa and the surrounding region, but will also include individuals from Częstochowa who acted nobly elsewhere.

In composing our list, we draw upon the resources of Yad Vashem, a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre in Jerusalem and the “Polish Righteous – Restoring Forgetten Memory”, a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw. We also include numerous others who, due to a lack of sufficient, first-hand evidence, have not been officially recognised as “Righteous” by Yad Vashem.

When reading their stories, it should be remembered that, in occupied Poland, the penalty for aiding Jews was death. In some cases, the Germans applied a collective responsibility which meant not only death to the person who extended that aid, but ALSO death to that person’s family.

This fact not only makes their deeds even more heroic and courageous, but it means that there are also “Righteous” about whom we will never know – those who were discovered by the Nazis and where they, their family and the Jews they were aiding were all shot – thereby leaving no one to even remember their names. May these heroes, together with those whom they endeavoured to help, rest in peace.

SIMPLY CLICK ON EACH NAME TO READ THEIR STORIES OF HEROISM.

During the German occupation of Poland, Zofia Batawia-Kłodnicka, a resident of Warsaw, traveled to Częstochowa to assist the Majzner family, with whom she was friendly. Upon her arrival, she found that she was unable to enter the ghetto, which was hermetically sealed. She managed to find their little son, Janek, whom she took back with her to Warsaw. On 23rd December 1982, Zofia was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

After the death of her husband and the rest of her family prior to the final liquidation of the Częstochowa ghetto, Roma Frydman succeeded in placing her six-year-old daughter, Ilona, in the care of Kazimiera Berczyńska, an elderly Polish teacher, who lived together with her son, Wacław, and his wife, Zofia. On 19th March 1986, Kazimiera, her son and daughter-in-law were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

For almost two years, during the Second World War, Józefa and Antoni Błoński, and Marta and Andrzej Skop hid teenager Tzvi Norich on their farms in Woźniki and Koziegłowy near Częstochowa. In 2010, Józefa and Antoni Błoński, and Marta and Andrzej Skop were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

In Częstochowa in 1943, Ita Dimant (née: Miodownik) and Yitzchak Berman found refuge, from the Germans who were searching for them, in the apartment of Henryk and Aniela Brust. The Brust family regarded their rescue operations as part of the war against a common enemy. On 4th September 1979, Henryk and Aniela Brust were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

In June 1943, Tzvi (Cwi; Jacek) Wiernik and Zyskind Szmuelewicz were sent to the HASAG Eisenhüttenwerke camp at the Raków foundry in Częstochowa. Through a friend, they became acquainted with Marian Brust, a veteran worker at the foundry. With the active assistance of Marian’s wife, Lucyna, the Brusts’ home became a centre for the relief of persecuted Jews. On 22nd December 1983, Marian and Lucyna Brust were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

As a doctor in Częstochowa, Tadeusz Ferens was known to many of its residents. In 1942, one of his pre-War friends and patients, Rut Asz, the daughter of Częstochowa Chief Rabbi Nachum Asz, asked him to help her reach the “Aryan side”. Jerzy, his son (pic left), recalls the night well. On 14th January 1985, Tadeusz and Wanda Ferens, as well as Irena Pawłowska, were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

Maria Kos (pic left) and Małgosia Korngold became good friends in their high school years. After the Częstochowa ghetto was established, Maria would bring her friend’s family basic amenities from the “Aryan side”. In 1984, Maria was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

Bogdan Jastrzębski (pic left) and Krystyna Geisler met in 1940. Despite the hatred all around them, they quickly developed a beautiful bond. Bogdan and his mother rescued Krystyna and her father Arnold. In 1994, Maria and Bogdan Jastrzębski were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

When Stanisława Klewicka received a postcard, postmarked “Częstochowa”, from her childhood friend Jadzia stating that she was ill, she immediately went there. Together with her son Leszek, she brought six Częstochowa Jews to their two-storey villa in Radość near Warsaw, and helped them to survive the War. On 8th September 1993, Stanisława and Leszek were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “The Polish Righteous – Restoring Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

During Nazi occupation, Maria and Anna Koźmińska lived in Częstochowa. During the years 1943-1945, they hid a Jewish boy, Abraham Jabłoński, an escapee from the Częstochowa ghetto, and three other Jews. On 11th February 1991, Maria and Anna Kożmińska were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Sadly, Anna Kożmińska passed away on 24th March 2021. She was almost 102 years old.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

Częstochowa-born Piotr Kwarciak lived in the suburbs of Dubno (then Wołyń county, today Ukraine) together with his wife Maria (née Broczek) and their sons Feliks, Anatoliusz and Alfred. One night in August 1942, fifteen fugitives from the Szybna Mountain execution site, including six children, came to the Kwarciaks’ house, asking for help. The Kwarciaks knew them all from before the War and decided to help. In 1992, Piotr, Maria and their three sons were all recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

In August 1942, Helena Fiszhaut obtained false documents for herself and her daughter. They managed to escape from the Warsaw ghetto and headed to the home of Aldona Lipszyc, Helena’s high school friend. Aldona took them in and, after a few weeks, Ela was placed into a convent orphanage in Częstochowa. Helena remained with Aldona until the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising.. In 1996, Aldona Liszyc was posthumously recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

Stanisław and Honorata Mach lived in Częstochowa. Their daughter, Wanda, was a school friend of Lula Gliksman (later Zofia Barlas). When the Jews were moved into the ghetto, the two girls lost touch. In winter 1942-43, Lula appeared at the Machs’ house asking for shelter. On 29th June 1995, Stanisław, Honorata and Wanda Mach were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

Wilchelm Maj extracted a little girl, Ida Paluch, from the Sosnowiec ghetto and took the child to his home in Częstochowa. Although his wife, Józefa, was pregnant, she did not hesitate to warmly welcome Ida into her home.. On 22nd March 2011, Wilchem and Józefa Maj were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

During World War II, in Częstochowa, Maria Markowska, together with her daughters Natalia Matysiak (nee Markowska) and Cecylia Łosik (nee Markowska), hid Danuta Reichental (nee Perelmuter), providing her with goods necessary for life and with false documents. On 24th March 2018, Maria, Natalia and Cecylia were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

In the summer of 1942, Sara Rajnherc fled with her two children during the final liquidation of the ghetto of Pabianice, near Łódż. After much suffering and hardship, the three fugitives arrived in the village of Janów, near Częstochowa, where they found refuge in the home of Józef and Stanisława Mencik. On 27th January 1993, Józef and Stanisława Mencik were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

In the autumn of 1942, during the deportations from the Częstochowa ghetto, Yitzhak and Bela Horowitz managed to escape from the ghetto together with their five-year-old son. Through a relative, who was hiding on the “Aryan side”, they were referred to the home of Wacław Miłowski, a factory worker, who, together with his wife Helena, agreed to provide refuge for the desperate refugees. On 24th January 1978, Wacław and Helena Miłowski were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

In the autumn of 1942, Franka Beatus managed to escape during the deportations from the Częstochowa ghetto. She somehow arrived at the home of Zygmunt and Henryka Mielczarek, friends of the family, and after asking them to hide her, they provided her with protection and prepared a well-concealed hiding place for her in their apartment. On 3rd March 1983, Zygmunt and Henryka Mielczarek were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

From December 1941, in Częstochowa, the Mrożek family provided shelter and false documents for six Jews, among whom were two members of the Weksler family. On 29th January 1992, Stanisław, Waleria and Daniela Mrożek were all recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

Fritz Mühlhof was born in Hagen/Westphalia in 1902. During World War II, he commanded the factory guard at Raków near Częstochowa. In that capacity, he supported the activities of the underground Jewish Fighting Organisation (ŻOB) and allowed its leaders to move freely between the labour camp at Raków and the outside world. On 21st September 1978, Fritz Mühlhof was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read his story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

In 1943, in the Myszków District near Częstochowa, fifteen-year-old Jerzy Nędza (pic left as an adult) came upon a terrified, half-naked boy, Mojżesz Rozenbaum. He decided to bring him home to his parents, Franciszek and Elżbieta (née Napora), who, together with numerous family members, ran a large farm. On 1st April 2001, Franciszek, Elżbieta and Jerzy Nędza were all recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

In 1942, after the Germans had begun liquidating the Włoszczowa ghetto, in the Kielce district, Rachel Rosenzwieg appealed to her friend, Konrad Nowak, for help. Risking his life, Nowak moved her and her brother, Israel, to Częstochowa. Israel entered the local ghetto, where he found work in the HASAG factory. Nowak found Rachel a place to stay with a local Polish family, introducing her as his fiancée. On 25th March 1996, Konrad Nowak was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read his story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

When the presence of two Jewish workers, in his glass-making factory in Częstochowa, began to arouse suspicion, Mieczysław Rylski reached out to the Albertine convent in the city. He explained the situation to the mother superior, Sister Vita (Józefa Pawłowska), who permitted the girls to move into the nuns’ house. At the convent, only she knew that the girls were Jewish. On 21st January 2014, Józefa Pawłowska was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

In 1941, before Irena Weksztein’s parents were deported from Częstochowa to a forced-labor camp, they found a way to make contact with Kamilla Pelc, who, motivated by her love of humanity and without asking for or receiving any remuneration, agreed to take their two-year-old daughter under her care. On 30th March 1998, Kamilla Pelc was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

Mikołaj Pietrzak and Samuel Broder knew each other well before the War. During the occupation, the Broder family moved from Warsaw to Częstochowa. Freeing Samuel’s daughter,Sonia, from the ghetto was a difficult task. Mikołaj could not enter the ghetto, so he sent his own 12-year-old daughter, Helena. On 8th May 1979, Mikołaj and Helena (pic left, as an adult), were both recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

After entering the Łódż ghetto three times to escort out three Jewish teenage girls, Natalia Drożdż (nee Pisula) hid two of them, Rozia Paryż and Golda Fogelman, in her apartment and placed Golda’s sister, Pesa Fogelman, in her parents’ home in the village of Herby near Częstochowa. On 29th November 1979, Michał (pic left), his wife and daughter were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

Between 1916 and 1923, Bronisława Płaskacz (pic left) was a nanny for the Bugajer family in Częstochowa. During the occupation, when they were interned in the ghetto, Płaskacz visited them regularly and offered them her assistance. When the situation worsened, Płaskacz tried to persuade the Bugajer family to flee to the “Aryan side” of the city. On 14th December 1965, Bronisława Płaskacz was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

Among Stefan Rak’s many Jewish friends were Salomon Markowicz, a work colleague, his wife, Rozalia, Hela Parnes, and her brother. In June 1943, after the liquidation of the Częstochowa ghetto, the Markowicz couple, Hela and her brother fled to the Raks’ home asking for refuge. On 24th February 1988, Stefan Rak, his mother, Agnieszka Rak and his sister, Helena Błaszczyk (née Rak) were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

While in Warsaw, Mieczysław Rylski, a glass manufacturer from Częstochowa, met the sisters, Paula and Hanna Kornblum. Finding themselves without employment and in danger because of the uprising, the girls approached him for help. They told him honestly that they were Jewish, but Rylski said that if they could get fake work permits, he would employ them. On 21st January 2014, Mieczysław Rylski was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read his story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

The Sikora family lived in Częstochowa, in a company-owned settlement of the Pelcery textile factory, where Stefan (pic left) was employed. Under Nazi occupation, the Germans merged Pelcery with the factory owned by the HASAG corporation and began manufacturing arms. On 27th January 1982, Aleksandra was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations. On 12th September 1990, Stefan and Jerzy were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

For almost two years, during the Second World War, Marta and Andrzej Skop and Józefa and Antoni Błoński hid teenager Tzvi Norich on their farms in Koziegłowy and Woźniki, near Częstochowa. In 2010, Marta and Andrzej Skop and Józefa and Antoni Błoński were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

When Yitzhak and Bela Horowitz and their son, Edward, were in hiding in Częstochowa, Aleksander Sosna helped them by providing them with funds for their upkeep, maintaining that this money had come from their friends. On 24th January 1978, Aleksander Sosna was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read his story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

Genowefa Starczewska (pic left) lived in Częstochowa. Frightened by the imminent liquidation of the “Small Ghetto,” Zygmund Berkowicz informed Genowefa about his plans to escape. When he fled the ghetto, he put his four-year-old child, Celina, into Genowefa’s care. In early July 1944, Genowefa was compelled to go into hiding, because her neighbours began to suspect that Celina was Jewish. On 14th May 1984, Genofewa Starczewska was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

The Szlama family had a farm in the village of Cykarzew, near Częstochowa. Although their village had no Jews, on Christmas Eve 1942, two Jews, 50-year-old Mosze Lichter and his 20-year-old cousin Mordechaj, knocked on the Szlamas’ door. In 1988, Stanisław and Marianna Szlama and their daughter Stanisława Włodarz were all recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

Antonina Świerczyńska (nee Niemczyk), along with her husband and son, lived in Czestochowa. Before the War, she worked as a domestic helper for the Jakubowicz family. In 1941, because the Jakubowicz family’s apartment remained within the ghetto borders, Antonia had to leave. Nevertheless, she maintained close contact with the Jakubowicz family. On 29th October 1995, Antonina Świerczyńska was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

Before the War, Wiktoria and Marian Urbańczyk lived in Dąbrowa Górnicza and, in 1940, moved to Częstochowa. There, they took in and adopted Elzbieta Asz (pic left, as an adult), great-niece of the late Chief Rabbi of Częstochowa, Nachum Asz. On 10th February 1997, Marian and Wiktoria were posthumously recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

During the War, Janusz Twornicki (pic left) lived in Częstochowa. In early 1942, he found his way to Otwock, near Warsaw, to visit friends who lived in the local ghetto. Shortly prior to the liquidation of the Otwock ghetto, David Krymołowski, his wife, and two sons managed to get to Warsaw and, from there, David phoned Janusz and told him that, in a few hours, they would be in Częstochowa. On 4th April 1967, Janusz Twornicki was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read his story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

In the late autumn of 1944, the Wieczorek family of Częstochowa took into their home a fifteen year old refugee from Warsaw who introduced himself as “Józef Balicki”. He was Bronisław Weissberg, who had arrived in a transport, weighing around 30 kg. and suffering from dysentery. In 2009, Stanisława was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

In 1939, with the War approaching, Częstochowa-born Anna Żmigrodzka, (née Wilniewczyc), pic left, lived with her parents, Wacław and Maria Wilniewczyc, in Zielonka near Warsaw. In the summer of 1942, Róża and Ida Beglaiter, two Jewish escapees from the Lwów ghetto, came to their home. On 12th December 1985, Wacław, Maria and Anna were all recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

Walentyna rented a house in Olsztyn, not far from Częstochowa, for Mieczysław Morgenstern and his family. She provided them with food and false papers and any support that was necessary for them to survive. In May 1985, Walentyna was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations and was granted Honorary Citizenship of the State of Israel.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

Częstochowa-born Father Mieczysław Zawadzki was ordained as a priest at 22 and, on 30th April 1938, he was appointed parish priest of the Holy Trinity parish in Będzin. When the Germans set fire to the Będzin synagogue, Father Zawadzki came to the rescue of the fleeing Jews, who had poured onto the street near his church. In 2007, Father Zawadzki was posthumously recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read his story.

(Courtesy: “Polish Righteous – Recalling Forgotten Memory”

– a project of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews)

Jerzy Zembik was a Polish worker in the HASAG factory where Jews were used as slave labourers. In 1942, Lusia (Łucja) Wajsman was sent to the camp as a slave labourer, her parents and sister having been deported to Treblinka. One day, Jerzy approached Lusia, saying that he could help her to get out of the camp. On 8th September 1986, Jerzy Zembik was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read his story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

Henryk Zielonka was a tailor and ran an underwear factory in Częstochowa. He married Gertruda when he was already a widower and had two sons from his previous marriage. In the summer of 1943, one of Henryk’s son brought home a five-year-old Jewish girl named Chana (later Chana Batista), who had been born on the outskirts of Częstochowa, in Raków. On 12th April 1992, Henryk and Gertruda Zielonka were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read their story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

Eugenia Zugaj, a deeply religious widow, lived together with her son, Julian, in Częstochowa.. Following the liquidation of the ghetto, she was approched by a stranger, Perla Schwarzbaum, to shelter her four-year-old daughter Halinka. Around the same time, Eugenia was approached with a request to take a three-year-old boy, named Maciek Mekler, under her care. On 28th April 1989, Eugenia Zugaj was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations.

Click HERE to read her story.

(Courtesy: Yad Vashem – a project of the World Holocaust Remembrance Centre)

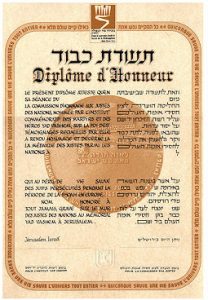

The Medal & Certificate awarded by Yad Vashem, in Jerusalem, to the “Righteous Among the Nations”

From the Webmaster:

If anyone knows the names and details of other heroes whose stories should be included on this page, please email them to me (click on the envelope symbol at the top right-hand corner). I will then pass them on for further research and future inclusion.

The saving of Jews or providing Jews with help needs to have taken place

(a) in Częstochowa or the surrounding region,

OR

(b) elsewhere by someone whose hometown was Częstochowa or in the surrounding region.

They do NOT necessarily need to have been recognised by Yad Vashem as “Righteous”.

Harry Rapaport's Family

Harry Rapaport's Family

- a Story of Tragedy and Survival

Harry Rapaport

Webmaster’s Note:

To anyone who has attended our Reunions, Harry and his wife Penny will have become familiar faces to you.

In this video, recorded on 1st May 2019 to mark Yom Ha’Shoah, Harry tells the story of his and Penny’s families – their Holocaust tragedies and stories of survival, to New York State Legislators, as part of their Holocaust Program.

His eloquence is highly moving and those of us who are descended from Holocaust survivors, as are Harry and Penny, will recognise many of the elements of Harry’s story in our own stories also.

From Harry Rapaport:

I’m retired as a court reporter from the US District Court in NY.

After bringing back Torah Scrolls from Częstochowa in 1988 & 1989, I began to tell the story of the rescue of the Torahs and the restoration of 15 scrolls, which mushroomed into my giving combined lectures of the story of the Torahs in conjunction with my family’s suffering and surviving the Częstochowa Ghetto, the Łódż Ghetto, Treblinka, Auschwitz and other camps, and the liberation by Allied troops in 1945, including their search after liberated for any relatives that may have also survived. Finding no one, I speak about their life in the DP Camps and arrival in the US.

I also speak about my dad’s father being the first Jew killed on “Bloody Monday”, 4th September 1939, and his burial in the Częstochowa Jewish cemetery, and my dad’s arrival to Treblinka on 2nd October 1942, with his 69 year old mother, his pregnant wife, his 11 year old daughter Esterka, their immediate death in gas chambers, and fate that my dad had the luck to sneak into a work detail (sorting clothes) while naked and only meters away from gas chamber; and his escape and plans for escape from Treblinka.

I lecture on the subject whenever asked, never taking any fee. It’s a legacy I inherited from my dad, Moishe RAPAPORT z’l.

A Memorial from Melbourne, Australia

A Memorial from Melbourne, Australia

In Memory of the Jewish Martyrs of Częstochowa

My name is Leon Rayman and, as President of the Częstochowa Committee in Melbourne, I would like to relate to the Jewish students of the Sholem Aleichem School, what happened to Częstochowa Jewry

I would like, today, to fulfill the last request of our martyrs, who went on their last journey to the gas chanbers and who demanded of those of us who survived the Holocaust, to tell our children, grandchildren, and the whole world, what the Nazi German murderers did to the Jewish people, and also to the Jews of our city, Częstochowa. We should never forgive or forget the murderous Nazi German nation!

Today, we will be talking about a city that existed in Poland, in which a third of the general population were Jews. The name of the city was Częstochowa. It is the history of the destruction of Częstochowa Jews, who shared the fate of all Polish Jewry.

However, the history of the destruction of Częstochowa Jews is not just a tale of blood and tears, because they had written an important chapter in the history of Polish Jewry. Through their heroic battle against the Nazis, they immortalised themselves in the history of the Jewish people.

This was our home. There, we and our forefathers built institutions that bound Jews together. Jewish energy, Jewish spirit and creativity existed in all corners of the city.

It was a concentrated centre of Jewish organisations. There were two Jewish high schools who, each, produced students entering universities; a technical school for tradesmen – locksmiths, carpenters and electricians; a school for gardeners, a Jewish hospital, an old-age home and a hostel for needy travellers. There were also Jewish newspapers, and Jewish primary and secondary schools in which the children received their modern Jewish education. There were synagogues, cheders, Jewish lecture halls and yeshivas in which Jewish children recived their religious education.

The Jewish population of Częstochowa was about 35,000 and the surrounding districs contained an additional 15,000 Jews. Thus, there were 50,000 altogether. This no longer exists. Not the people, nor their creations. Isolated from the external world, from everything and from everyone, tragedy befell them. They were torn away from us with the most shocking force in the most dreadfulo manner – and sent to their destruction.

At midnight, at the conclusion of Yom Kippur, the ghetto came under tight guard though cordons of black-uniformed thugs of the murderous German extermination squads. This was the first sign of the great tragedy which was to come. This was a night in which all the Jewish mothers cried until there were no more tears. Every minute was an tragic eternity – minutes of tension, minutes of deep sorrw and of horrible uncertainty. This happened on Tuesday, 22nd September 1942 – one day after Yom Kippur.

This was the first mass slaughter of 7,000 Częstochowa Jews who were, on that day, deported to Treblinka where they were destroyed by gas and flames. From September 22nd to October 4th 1942, five such selections and deportations took place, which decimated the Jewish community of Częstochowa and the surrounding area. The entire Jewish population of Częstochowa was disrupted and destroyed. It is impossible to describe the tragic, petrifying terror and anguished cries of the Jewish mothers and orphaned families.

It is the duty of Holocaust survivors, and living witnesses of the sea of blood and tears, to remind us, each year, of the destruction of our city of Częstochowa and the entire Jewish population. We should never forgive and never forget! By describing the Holocaust, we are able to visualise the atrocities that brought about the destruction, by the Nazi murderers, of the Jews of Częstochowa and of one-third of the entire Jewish people.

Our blood boils and our clenched fists rise up against the murderers of the Jewish people. It is most painful, and our suffereing makes us scream in agaony. Our hearts and souls are bleeding and, as living witnesses of the Holocaust, we dare not allow the world to forget what the Nazi murderers did to the Jewish people. Immersed in deep sorrow and with bowed heads, let us say Yizkor for the holy martyrs of Częstochowa.

Yizkor for the holy mothers and fathers.

Yizkor for our brothers and sisters.

Yizkor for our wives and children.

Yizkor for the ghetto heroes and partisan fighters of the heroic resistance movement

who, through their resistance and battles, raised the national dignity of the Jewish

people, and who helped carry the banner of eternal Jewish existence, the banner of

“Am Yisroel Chai”.