Lives & Legends

Write a Tribute

- for the "Lives & Legends" section of our website

their grandparents or other members of their nuclear or extended family,

who either survived or perished in the Holocaust.

- In fact, anyone who wishes to may write a tribute page to some or all of their family,

so long as their family comes from Częstochowa or the surrounding area.

- Each tribute should be a maximum of 1,500 words (in WORD or plain text format)

and MUST be accompanied by at least 2 or up to 4 photographs (a page of plain text

without a pic or two does not look good at all)..

- Each tribute should be headed CLEARLY with the names of the people being written about.

- You may submit a tribute for as many families as you wish – but please,

write each one SEPARATELY.

- Please state clearly the name you want to appear as the author of the tribute and,

optionally, your relationship to the family being written about.

All tributes

should be

emailed to

the Webmaster

at

aragorn@axiomcs.com.au

Sigi z"l & Hanka Siegreich

Sigi z"l & Hanka Siegreich

- a love story: Częstochowa Holocaust survivors celebrating seven decades of marriage

Melbourne Australia couple Sigi (93) and Hanka (91) say after all of these years they are still very much in love.

Melbourne Australia couple Sigi (93) and Hanka (91) say after all of these years they are still very much in love.

Having virtually grown up in labour camps, the teenagers were both wasting away when their eyes first locked in the Częstochowa camp in Poland.

“I lost my mind,” Sigi says. “When I saw her, the whole world was turning around me. I saw a pair of beautiful eyes and I heard bells ringing.”

It was New Year’s Eve 1944, eighteen days before the camp was liberated by the Red Army.

“I had no interest in girls, because I was a skeleton,” Sigi says. “There was a pair of beautiful eyes looking at me, with a smile like I never saw in my life.”

He approached her and they talked. Before returning to his barracks he gave her a kiss on the cheek.

“I remember the first kiss,” Hanka says as she puts her hand on her face. That is exactly what she did on that first day because, she says, she wanted to hold onto it forever. Sigi had stood out in an environment where the inhumane conditions had left most people shells of their former selves.

“At that time, the people in the camp were terrible,” she says. “He was very gentle.”

Over the coming days, this new love was tested. Sigi had been working in the munitions workshop making bullets for the Nazi German army. He says he had been sabotaging the factory line making bullets too small for the gun barrels. When he received word that the Gestapo were looking for him, he found a hiding spot in a nearby abandoned construction site. He says only Hanka knew where he was hiding.

“She was the only person I could trust my life with,” he says.

Hanka says she risked her life to keep him alive smuggling him small pieces of her bread ration and a blanket that she had made to keep him warm on -15 degree nights. Then one night, she came for a second visit. This time, she was smiling and had her arms out. The camp was being liberated.

“They’re gone,” she told him. “We are free.”

The next day they were married.

The year after, Hanka gave birth to the first of their two daughters, Evelyne, the first baby born to Holocaust survivors in Sigi’s home town of Katowice after the war.

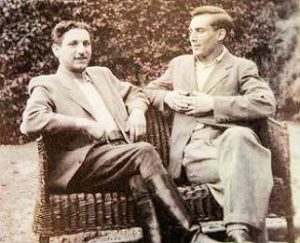

Sigi and friend Adam Frydman, a fellow camp inmate and witness to his marriage to Hanka.

Sigi and friend Adam Frydman, a fellow camp inmate and witness to his marriage to Hanka.

Sigi and Hanka Siegreich with

Sigi and Hanka Siegreich with

their daughter Evelyne in 1946.

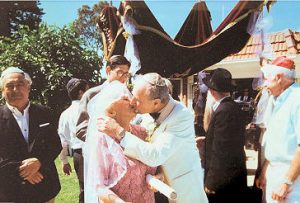

Having moved to Australia in 1971, it wasn’t until their 50th wedding anniversary that the couple had a proper wedding, in their daughter’s Melbourne backyard.

Having moved to Australia in 1971, it wasn’t until their 50th wedding anniversary that the couple had a proper wedding, in their daughter’s Melbourne backyard.

Amazingly, their witnesses were fellow inmates at the labour camp, who had also witnessed their 1945 marriage signing.

“We’ve achieved a lot,” Sigi says. “We’ve got so many grandchildren and great grandchildren. She charmed me. That was that, the rest was history.”

Unlike Hanka and Sigi, only a handful of their classmates survived the Holocaust. Their great-grandson’s school, Bialik College, is currently collecting 1.5 million buttons to honour the children who were murdered under the Nazi regime. Sigi is donating 180 buttons to the project this month, to represent the family he lost in the Holocaust.

The doting couple, aged 93 and 91, have already had their gravestones prepared, side by side, for when they leave this world. The inscription also commemorates their immediate family who were never given a grave.

“We are inviting the souls of our exterminated family to rest in our grave.”

[Webmaster: Sadly, Sigi passed away, in Melbourne, on 18th October 2019, at the age of 95.]

Sources:

Story by Margaret Burin

Australian Broadcasting Commission

News 24 TV

and

Material reproduced here

with the kind permission of

Sigi and Hanka Siegreich

Write a Tribute

Write a Tribute

- for the "Lives & Legends" section of our website

their grandparents or other members of their nuclear or extended family,

who either survived or perished in the Holocaust.

- In fact, anyone who wishes to may write a tribute page to some or all of their family,

so long as their family comes from Częstochowa or the surrounding area.

- Each tribute should be a maximum of 1,500 words (in WORD or plain text format)

and MUST be accompanied by at least 2 or up to 4 photographs (a page of plain text

without a pic or two does not look good at all)..

- Each tribute should be headed CLEARLY with the names of the people being written about.

- You may submit a tribute for as many families as you wish – but please,

write each one SEPARATELY.

- Please state clearly the name you want to appear as the author of the tribute and,

optionally, your relationship to the family being written about.

All tributes

should be

emailed to

the Webmaster

at

aragorn@axiomcs.com.au

Yaakov (Kuba) Wasilewicz

Yaakov (Kuba) Wasilewicz

- son of Halina Wasilewicz z"l

“Because You are Jewish” – the Story of a Young Man’s Journey from Poland to the Five Towns

I was born in Częstochowa, Poland, in 1988. Since there were no Jewish schools in Poland at that time, my mother sent me to public school. When I was 8 years old I came back home from school and I told my mother what the teacher told us that day – “Mom, tomorrow we can’t eat meat, we are going to church and the priest is going to pour ashes over our heads.” My mother looked at me and said, “Sure, if you don’t want to eat meat tomorrow, I will not give you meat to eat, but you will not go to church.” I asked, “Why not? She said, “Because you are Jewish.”

I was born in Częstochowa, Poland, in 1988. Since there were no Jewish schools in Poland at that time, my mother sent me to public school. When I was 8 years old I came back home from school and I told my mother what the teacher told us that day – “Mom, tomorrow we can’t eat meat, we are going to church and the priest is going to pour ashes over our heads.” My mother looked at me and said, “Sure, if you don’t want to eat meat tomorrow, I will not give you meat to eat, but you will not go to church.” I asked, “Why not? She said, “Because you are Jewish.”

This is when I found out for the first time that I was Jewish. Since that day, I knew that I was Jewish but I didnt understand what it meant to be a Jew. All my friends from school would go to church and I was the only one who didn’t. When I was asked which church I belonged to, I would have to lie and make up a name. I once told my best friend in school that I was Jewish and the next day I was called by everybody a “dirty Jew”. That taught me to keep my mouth shut and not to tell anyone my secret.

For many years, my parents and I would attend a summer and winter Jewish camp in Poland called The Lauder Camp. This camp was a place where all the Jewish families from the whole Poland would come and spend a few weeks learning about Judaism. The camp was for all three generations of Polish Jews: Holocaust survivors, their children and grandchildren. Once I knew I was Jewish, it was refreshing to be in a place where I didnt have to hide my true identity the secret of who I was. There, everyone was Jewish and everyone felt comfortable. There, for the first time, I learned my favorite song, Modeh Ani, and I would sing it everywhere I went. I would even sing it in my school.

Above: R’Yonah Bookstein and I sing Modeh Ani at the Lauder Camp in Rychwald, Poland

Right: My mother, me and an older Jewish woman lighting Channukah candles at my mother’s Jewish Centre.

Aside from camp, I had another source for my Jewish education – my mother. My mother was the child of two Holocaust survivors – Braindl (nee Cwajghaftig) and Yankiel Wasilewicz (pic left). It was very hard to keep anything Jewish after the war, but they ried and they did. My mother’s mother lit the Shabbos candles, and my mother’s father made Pesach sedarim. My grandmother would take my mother, as a little girl, for the Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur prayers to the “Congregation”, an old building in Częstochowa that housed the mikvah before the War. My grandfather used to do kapparos at home with my grandmother and my mother and would then bring the chickens to the shochet. Whatever they did after the War, even though it was hard for them, that’s what my mother knew, and that’s what she taught me.

Aside from camp, I had another source for my Jewish education – my mother. My mother was the child of two Holocaust survivors – Braindl (nee Cwajghaftig) and Yankiel Wasilewicz (pic left). It was very hard to keep anything Jewish after the war, but they ried and they did. My mother’s mother lit the Shabbos candles, and my mother’s father made Pesach sedarim. My grandmother would take my mother, as a little girl, for the Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur prayers to the “Congregation”, an old building in Częstochowa that housed the mikvah before the War. My grandfather used to do kapparos at home with my grandmother and my mother and would then bring the chickens to the shochet. Whatever they did after the War, even though it was hard for them, that’s what my mother knew, and that’s what she taught me.

Since 1974, my mother has been working for the Social and Cultural Society of Jews in Częstochowa. Throughout the years, she worked hard to teach those Jews who were left in Częstochowa about the Jewish holidays. She organised events, inviting actors from the Jewish theatre in Warsaw to come to Częstochowa, hosting famous artists, writers, musicians, etc.. At this Jewish Centre I learned a lot about Judaism, but still it was not enough for me. I wanted to learn more.

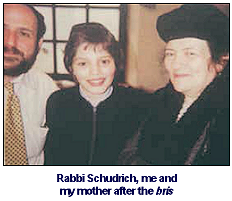

When I was 12 years old, my mother started to think that it would be nice if I would have a bar mitzvah. She called Rabbi Michael Schudrich, who is Chief Rabbi of Poland today, but who back then was the Chief Rabbi of Warsaw and Lodz, and she asked him if he could teach me and prepare me for my bar mitzvah. He then asked my mother, “But does he have a bris?” My mother honestly said, “No”.

When I was born, there was no mohel in Poland, so I couldn’t have a bris when I was 8 days old. Therefore, I was never circumcised. The rabbi told my mother that I need to have a bris and that he wold try to arrange everything. A few days later, we got a phone call that the mohel (Rabbi Fisher, from Monsey, NY) will come to Poland just for me, so that I can have a bris, and that we should come to Warsaw where my bris would take place. So that’s what we did.

It took us three hours by train to get to Warsaw. After we got to the Jewish quarter and entered the Nozyk Synagogue, the main synagogue in Warsaw, we were informed by Rabbi Schudrich that, unfortunately, Rabbi Fisher was unable to come because something went wrong with his flight. We turned around and went back to Częstochowa. A few days later, we got another phone call from Rabbi Schudrich. He assured us that, this time, Rabbi Fisher would be able to come and that we should come once again to Warsaw. So we did. When we got to the Jewish quarter in Warsaw, we entered the Jewish theatre which is not far from the synagogue. We ate something there, and there we met my mother’s friend.

She asked us what we were doing in Warsaw so my mother told her the truth. She right away took me aside and tried to convince me not to do it. She said that it’s like cutting off my arm. After she was done, I thanked her but I told her that I was a Jewish boy and, if a Jewish boy has to have a bris, I’m having it!

We went to the synagogue. There, we met with Rabbi Schudrich and Rabbi Fisher. That day was a day after the yahrtzeit of the famous Rabbi Elimelech of Lizensk, Poland. Thousands of Chassidim were coming back from Lizensk and going to the airport in Warsaw. Before going to the airport, some of the Chassidim decided to visit the synagogue. They came in and they saw that something was going on there, and one of the Chassidim became my sandek. His name was Rabbi Yaakov Yossef Neushloss. Afterwards, we were dancing in a circle and my sandek asked me for my address and my phone number. I gave him my address and my phone number and then my mother and I went back to Częstochowa.

We went to the synagogue. There, we met with Rabbi Schudrich and Rabbi Fisher. That day was a day after the yahrtzeit of the famous Rabbi Elimelech of Lizensk, Poland. Thousands of Chassidim were coming back from Lizensk and going to the airport in Warsaw. Before going to the airport, some of the Chassidim decided to visit the synagogue. They came in and they saw that something was going on there, and one of the Chassidim became my sandek. His name was Rabbi Yaakov Yossef Neushloss. Afterwards, we were dancing in a circle and my sandek asked me for my address and my phone number. I gave him my address and my phone number and then my mother and I went back to Częstochowa.

A few months later, I had a bar mitzvah in a yeshiva in Kishinow, Moldova, where for the first time I learned the Hebrew alphabet, just to be able to read the blessing before and after the reading of the Torah. The rabbis at that yeshiva found out that I love music, so they offered me that if I stay in the yeshiva, they will get me a private music teacher. But my mother would have to go back to Poland. I was only 13 years old and I didn’t want to stay by myself in a foreign country, so I went back to Poland with my mother.

Now I had a bris and a bar mitzvah – but I was still in a public school.

After the summer, we were invited by the Jewish Community of Warsaw to come to Warsaw for Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. We came and we were staying in a hotel there. After the holidays, I asked Rabbi Schudrich if he could help me come to Warsaw so that I could learn in the Lauder Jewish School there. I told him that, in Częstochowa, there was not much of a Jewish life. “Im in a public school, there is no synagogue in Częstochowa – and in Warsaw there is.” He told me that he will see what he can do.

A few months later, we got a phone call that Rabbi Schudrich had found us a place to stay and that we could come to Warsaw if we wanted to. We chose to go. At that time, I was 14 and I was in a middle of 8th grade. We moved to Warsaw for a year and a half.

In the Lauder school, I learned Jewish history, Jewish culture, and Hebrew language, but not Torah. After school, I had a private teacher who taught me how to put on tefillin and he got me a pair of tzitzis. I started to remind myself how to read Hebrew and started to pray, but only on Shabbos. I started to keep Shabbos and kosher as much as I could.

Sometime during that year, I got a phone call from my sandek, Rabbi Neushloss, that he was in Poland and he would like me to join him for a tour and for the yahrtzeit of Rav Elimelech of Lizensk. He sent a private driver who came to Warsaw, picked me up and brought me to where a bus full of Chassidim was waiting for me. We went from one cemetery to the next, from one shul to the next. Eventually, after a whole day of driving, we got to our final destination Lizensk. There, I spent the most amazing Shabbos of my life. The streets of Lizensk were filled with Chassidim.

This was the second time in my life seeing Chassidim. The first one was at my bris. It felt like I was in a different world. At the Shabbos night meal, thousands of Chassidim were eating together, singing together and, afterwards, dancing together. When everyone was dancing, the whole floor was shaking! It was an unbelievable experience. Sunday was the yahrtzeit and everyone, including me, was praying at the grave of the holy Rabbi Elimelech.

After the yahrtzeit, when we got back to Warsaw, Rabbi Neushloss (pic left: standing with me) asked me if I would want to come to his house for Pesach. I answered, “Sure”, but in my mind I was thinking about how I would be able to pay for the ticket. But I thanked him for everything and said goodbye. Some time before Pesach, I got a phone call from Rabbi Schudrich that Rabbi Neushloss sent him a ticket for me to come to his house in Monsey, NY. So I went. I spent a really beautiful Pesach there and, afterwards, I decided to visit a rabbi whom I knew from the Lauder Camp in Poland, Rabbi Lieber, who would travel to the camp from America to teach Polish Jews at the camp about Judaism. I told the rabbi that I was in the Lauder Jewish School but I didn’t know where to go after my graduation, since there were no Jewish high schools or yeshivas in Poland. He told me that he would try to look for something for me.

After the yahrtzeit, when we got back to Warsaw, Rabbi Neushloss (pic left: standing with me) asked me if I would want to come to his house for Pesach. I answered, “Sure”, but in my mind I was thinking about how I would be able to pay for the ticket. But I thanked him for everything and said goodbye. Some time before Pesach, I got a phone call from Rabbi Schudrich that Rabbi Neushloss sent him a ticket for me to come to his house in Monsey, NY. So I went. I spent a really beautiful Pesach there and, afterwards, I decided to visit a rabbi whom I knew from the Lauder Camp in Poland, Rabbi Lieber, who would travel to the camp from America to teach Polish Jews at the camp about Judaism. I told the rabbi that I was in the Lauder Jewish School but I didn’t know where to go after my graduation, since there were no Jewish high schools or yeshivas in Poland. He told me that he would try to look for something for me.

In my last year in the Lauder School, right before the summer, I didn’t know what to do. All my friends were applying to different high schools and I was waiting for a phone call from Rabbi Lieber (pic right: singing with me). Finally, a month before summer, I got a phone call that I could come to a yeshiva in America. I got a visa and left Poland at the age of 15. I started learning in the Bobov Yeshiva in Boro Park. I learned there maybe for a month before switching to the Talmudical Academy of Baltimore.

In my last year in the Lauder School, right before the summer, I didn’t know what to do. All my friends were applying to different high schools and I was waiting for a phone call from Rabbi Lieber (pic right: singing with me). Finally, a month before summer, I got a phone call that I could come to a yeshiva in America. I got a visa and left Poland at the age of 15. I started learning in the Bobov Yeshiva in Boro Park. I learned there maybe for a month before switching to the Talmudical Academy of Baltimore.

Since I didn’t know much about Yiddishkeit and I never really studied Torah before, I was placed in a second grade where, for the first time in my life, I learned Chumash. I remember when, for the first time, I said a pasuk from the Chumash, all the kids in the class were clapping. That same year, I went to the 4th grade and there, for the first time, I learned mishnayos. Next year, I went to the sixth and the eighth grades where, for the first time, I learned gemara. A year later, I went to the tenth grade and a year after that I went to the twelfth grade and graduated high school in 2008.

After graduating from the Talmudical Academy of Baltimore, I went to Yeshiva Shor Yoshuv in Lawrence, NY, where I am today. Aside from making lifelong friends and learning a lot of Torah in Shor Yoshuv, ironically, I was told that the song Modeh Ani, which was and still is my favorite song, was composed by a rebbi who taught in Shor Yoshuv for many years – Rabbi Shmuel Brazil!

Living as a Jew in Poland was not easy. It was like living in darkness. I tried to put all the puzzles together, but I was missing a lot of the pieces. Today, thanks to many great people and of course to Hashem, our G-d, I fully understand what it means to be Jewish.

I am forever grateful to my mother for letting me leave Poland to study in a yeshiva, even though I’m her only child, and to all the people that made my dream come true. The first words I utter every morning are for me as they are for all religious Jews a constant reminder that our lives are a journey guided by the hand of Hashem and that He brilliantly enlightens our path and guides us along the way – Modeh ani lifanecha.

Yaakov Wasilewicz

Yaakov is the son of Halina Wasilewicz z”l, former long-serving Chairperson of the Częstochowa branch of the TSKŻ – the Social and Cultural Association of Jews in Poland.

This article originally appeared in The Jewish Home on 8th May 2014 and is reproduced on this website with Yaakov’s kind permission.

Yaakov welcomes your questions and comments.

He can be reached at:

jakub.wasilewicz@gmail.com

Webmaster’s Comment:

I first met Yaakov when he was a young boy in Warsaw back in 1998 and, over the years, having met him fairly regularly, both at our Reunions and on other occasions in Warsaw, Częstochowa and New York, I’m proud to call him my friend.

His story is one that I hope will inspire other young Polish Jews to learn more about, and embrace, their Jewish heritage.

Halina Wasilewicz z"l

Halina Wasilewicz z"l

- long-serving Chairperson of the Częstochowa Branch of the

TSKŻ (The Social and Cultural Association of Jews in Poland)

Please introduce yourself and explain the function you perform. Let’s also talk about the history of your family, about your parents and where you come from.

Please introduce yourself and explain the function you perform. Let’s also talk about the history of your family, about your parents and where you come from.

My name is Halina Wasilewicz. I was born in Częstochowa. I’ve been branch Secretary of the TSKŻ since 1974. At the present time, I’m both Secretary and Chairperson. I sometimes jokingly say that I’m a child of the TSKŻ, since I spent youth growing up at the Częstochowa TSKŻ club.

My parents come from different sides of Poland. My father was born in Kuźnica Stara, not far from Częstochowa. From the age of ten, he lived in Częstochowa. My mother was born in Opoczno. After she married, she lived in Łódź and was transported from the Łódź ghetto to the HASAG slave labour camp in Częstochowa.

My father was very connected to Częstochowa. Like the majority of Jews, he was part of a large family. He didn’t talk much about his family. I can’t even tell you for certain how many siblings he had. I know about one brother for sure. I know that he had three daughters, two sons-in-law and a grandson born in 1940. That was my father’s closest family.

My mother came from a large family. She had five siblings. Some lived in Łódź, others in Opoczno. After getting married, one of the sisters lived with her husband in Ozorków. From that entire family, and I can’t even tell you how many there were, only my mother survived. When she left the Łódź ghetto, she had no idea where she was being sent. As it turned out, it was to Częstochowa and, as I sometimes tell my son, she never complained about her fate. Wherever she was sent, she coped with the situation and didn’t try to change anything. Only once did she change something – for a few hours prior to the liberation of Częstochowa. Of course, everything I know is based on what I heard from my parents. I used to eavesdrop on their conversations in Yiddish because they never discussed these things with me directly.

Yiddish was spoken at home?

Yes. My parents used it when speaking with each other. They spoke in Yiddish when talking about things that were not meant for my ears and I, just to be contrary, learned the language – how I don’t know.

It just flowed into your head?

Yes, it just flowed in.

My mother said that, in the HASAG camp, those who weren’t working on any shift would be forced into the barracks square and then loaded onto railway wagons. As the Germans sensed that the liberation army was nearing Częstochowa, they didn’t make their escape alone. They took some of the Jews with them – those who were not working.

This was the only time when my mother tried to change her situation. Of course, she was prepared. She stood on the barracks square with her rucksack and said to her friend,”Mania, come over to this incomplete hundred”, because prisoners were counted off in groups of one hundred and then packed onto railroad wagons. After a moment, they found themselves in this incomplete hundred. The loading of prisoners finished, and the Germans left. My mother remained in the camp with the other Jews. She didn’t know Częstochowa. She heard a voice say, “I know the way to Częstochowa. Let’s go”.

A group of them then formed which my mother joined. I don’t know how many of them there were. She went with a woman from Skarzysko-Kamienna who had been transported there, maybe, in mid-1944. As it was January and fairly frosty, she somehow lost her way and, instead of going with the group, she headed outside of Częstochowa, in the opposite direction, to the town of Olsztyn.

Apparently, she came to some railway crossing and came upon a railway crossing attendant. He looked at the two women with a child, recognised straight away where they had come from and said, “I can vouch for myself, but not so much for my substitute co-worker” and pointed to a house nearby. He said that they’d be able to stay there. The housewife said to my mother, who at the time was a little over thirty years old, “Grandma, please sit down”. I don’t know how my mother must have looked, dressed in rags. She stayed there for a few days in order to recover her strength, as she was unable to walk any further. The woman who had accompanied my mother came from Kielce and headed off in that direction.

After staying there for a few days, some Russian soldiers brought her to Częstochowa. There was a building at 19 Garibaldi Street (ul. Garibaldiego 19), which the Germans had most probably used as a storehouse. Maybe Germans had even lived there and then abandoned it straight after liberation. It was to there that Jews from Cz?stochowa headed first. My mother also ended up there and told me that this three-storey building was completely full of people who were lying on rags, on newspapers and on cardboard cartons. This was their accommodation. My mother asked, “Is there room for me to spend the night?” The response was, “There’s no room.”

Were all those people Jews?

Yes, all Jews from HASAG, but not only from Częstochowa. I’m talking about the first few days after liberation. I always mention that because, as assessed by historical researchers examining this subject, at that time it was the highest concentration of Jews in Poland over 5,000 people who had remained in the HASAG slave labour camp. I don’t know how many of those people were actually staying in that building.

Is that building still standing today?

Yes, it’s still standing at 19 Garibaldi Street (ul. Garibaldiego 19),

What happened then?

My mother went down to the ground floor, sat on the steps and began crying as she had nowhere to go. And it was at that moment that along came Wasilewicz. This is a family story which Ive passed on to my son. Mr Wasilewicz said, “Do my eyes deceive me?” Now I’ll tell you how they knew each other.

Together with a friend, my mother was transported to Częstochowa from the Łódź ghetto. They slept on the same bunk. That friend worked on the same shift as Mr Wasilewicz, my dad. After the liquidation of the ghetto in 1943, my dad was left with one worn-out suit. My mum had arrived from the Łódż ghetto with various items, among which were needles and thread. She loved to sew, to make things in her spare time. My mum’s friend took the suit from Wasilewicz and my mother mended it. That was the beginning of their acquaintance. My dad looked after my mother. As one of the older people, he brought some order to the place in which they spent the night. Later, he looked after my mother during the many years of their marriage.

And so they were married?

I don’t know what kind of wedding it was. It was most probably in the Registry Office. It proved to be problematic as some certification was required to prove that my father’s first wife was no longer alive – witnesses to her being transported to Treblinka. These are stories that I found out about many years later.

A little time passes and little Halinka comes into the world.

Yes, little Halinka. And it wasn’t that long after it was 1946.

What was Jewish life like in Częstochowa during your childhood years?

It existed. Despite the fact that my dad was not a religious person, for me he was very Jewish to such a degree that, when my parents were married in the Registry Office, the official said, Mr Wasilewicz, you have such a beautiful sounding Polish surname, why do you need to be called Jankiel? To which my dad replied, That’s the name my father gave me and Im not going to change it. I survived the occupation with it so, as a Jew, I’m not going to change it. Even after I was born, he wanted to register me under the name of my grandmother Chaja Ita or Chaita. Usually, children born after the War were given Polish names which sounded similar to Jewish ones, beginning with the same letter. After being persuaded by my mother, Chaita became Halina. But on my identity papers, there is no doubt – I am Halina Wasilewicz, the daughter of Jankiel and Brandl.

Were your parents active in the community? Do you remember your neighbours and acquaintances?

They were only active within the Jewish community. I remember our neighbours and acquaintances, but they were active exclusively in the Jewish community. I went to school …

To a public school, a state school?

A state school but it was a TPD (Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Dzieci – Society of Friend of Children) school.

Namely, without religion? It was without religion – actually without religion at that time. Later, in 1956, religion was introduced very briefly. It was the first secular school. 99% of its students were Jewish. It was not enough that we got together in the afternoons at the club, we were also together at school.

Where was the school located? On ul. Kopernika (Kopernikus Street). There’s an old building there. Before the War, it was probably Axer’s high school.

So that this was a continuation?

In a way it was. Later, a new school building was constructed on the other side of the street and that’s where the administration moved. That was the first secular school.

There were no Jewish school as such?

No. Perhaps, for a short time after the War, but I really don’t know. I know that there was a Jewish orphanage. Perhaps, for a short time, there was such a school, but I can’t recall it from memory.

Were your friends mainly all Jewish?

Totally – my friendships were all Jewish friendships.

Did you, as children, feel any sense of “otherness” or hostility in the neighbourhood?

Yes, but I didn’t sense it directly. It was quite funny – I laugh talking about it now. My parents would have sensed it differently. I don’t know how it is now but, in the schools in my time, twice yearly, perhaps more often, the best students were honoured with distinctions. It was a public event with all students participating. People from each class were singled out. At that time, I’d hear, “Only Jews, nothing but Jews”. Others were also singled out, but when they were Jewish, attention was always drawn to that fact.

I understand that Jews were not given nicknames.

Of course there were nicknames. It’s good that you brought this up. My awareness about who I am came precisely from my encounters in the courtyard. I know that once I came home crying from the courtyard because someone had called me Źydówa (Kike). My dad told me to sit down. He said, “Yes, you’re Jewish, because I’m Jewish.”

I replied, “No, no, I’m not because I was born near Jasna Góra. Maybe you are Jewish!!” That was a time when I didn’t understand certain things. Later, when I began to understand, after school, I would go only to activities at the Jewish club. It was a wonderful time. It was like a second home, a cultural home. There was a drama group. In the beginning, it was called Źywego Słowa (The Living Word), led by actors from the Częstochowa theatre. There were classes in Yiddish and Hebrew, a music group, an art group led, in the beginning, by Jurek Duda-Gracza, a very well-known artist. At that time, he was a teacher at the graphic arts high school. He was not Jewish.

Do you remember his classes?

Of course. We even have a chronicle kept by the youth club. He illustrated some of the pages in it. Right now, the chronicle is on display at the Upper Śląsk Museum (Muzeum Górnośląskim) in Bytom. We also have photos of walls which he decorated. Only it’s a pity that they’re not in colour. At that time, photographs were only in black and white.

How do you remember the events of 1968?

At that time, I was at university outside of Częstochowa. Each visit home provided me with more information about who was no longer around. My mum used to greet me, one could say, joyfully and repeatedly saying, “It’s so good that you’re not in Warsaw”. Because I’d begun studying international commerce in Warsaw and I’d go to the club at Nowogrodzką 5. I’d grown up in a club, and my first steps as an adult were aimed at a club. It was all a terrible hotbed there, so probably ….

What do you mean by “all a terrible hotbed”?

The ringleaders of the student riot came from Club Babel. Among them were a group of my friends, so that I would have become entangled in it also. Perhaps, that’s not how I felt at the time. But years later, I tried to understand how I had …. But

But you didn’t leave the country.

At that time, my dad was already not leaving the house. We didn’t have family and I felt obliged to stay. I don’t hide the fact that, many years earlier, I wanted to leave because, much earlier, before March, many from my surrounding area were gradually disappearing.

What did the Jewish Częstochowa landscape look like at the end of the 1970’s and the 1980’s?

Very sad. That’s precisely how I summed it up – that all our youth left, all my friends. At one time, in my recollections, I compared it to this – my father was sitting, poring over a book published, in Yiddish, by Częstochowa Jews from New York. He was looking at pictures of Częstochowa from the past. My Jewish Częstochowa was also now history.

Your whole circle disappeared?

All of it, precisely. Even using the fingers of one hand, I can’t say how many remained in Poland or in Częstochowa. I only see them now in TSKŹ photographs from various parties. Only a few, a dozen or so, came to the Reunion of Częstochowa Jews in 2012.

As a Jew, how did you feel in the 1970’s and 1980’s?

You just had to live an ordinary life. In 1974, it was proposed that the Częstochowa TSKŹ branch be shut down because, according to the authorities, there were no funds to employ a secretary.

Was there any protest?

I’m getting to that. In October 1974, everyone got together and said that, even if they were unable to come, they still wanted to be assured that something like that was still there.

How many people were still here then?

Over seventy, maybe almost one hundred. I’m not now able to say exactly how many. It was usual, at that time, to only have one person per family on the list. To that you would have to add the spouse and the children.

And that was the year when you began to become active?

Yes. At that gathering, the question was asked, “Is anyone running the social club?” And I, being active in the community, raised my hand and, for 16-17 years, I ran the social aspect of the TSKŹ. So from there, I went from the TSKŹ period of my youth to an official position.

Let me ask this – what did the events in Poland in 1989 mean to you personally, as a Jew? Of course, I include your son in that.

What it meant is that, right now, he is away from me. I have to say that it was life-changing.

To me, that’s unusual. You are someone who was active in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Suddenly, something unexpected happens. What was that like? How did it affect you?

It was strange. I remember that, when I was a child, there was the Social-Cultural Association (Towarzystwo Społeczno-Kulturalne) and there was also a Jewish religious congregation (Kongregacja Wyznania Mojźeszowego) which provided all the basic things. There was a shochet (ritual slaughterer), there was matzo, and the deceased were buried. Perhaps twice a year, a children’s gathering was organised. I even have photographs. I still have the flags which I got and which were draped on a kind of bar around the candles. I already showed you the memorabilia from my childhood. However, nothing was done to educate the next generation. I know that two or three boys had their Bar Mitzvah, but I don’t know if they were prepared for it as required. For their parents, it was probably very important. I know those boys.

Are they no longer in Poland?

One is here, and guess where – in the TSKŹ!

In Warsaw?

Yes.

I realise that I knew little apart from what I’d experienced at home and from what I heard from my mums stories. I remember that dad took the poultry to the shochet and that we brought matzo home. Once a year, I went with my mum to the pseudo-synagogue, to the Congregation. Even then, I still didn’t know why mum and I would stand in the corridor. That was used as the separate “room” – the men used the real room. My knowledge deepened at the Lauder Foundation camp in Rychwałd.

In the beginning, how did it affect you?

It enriched me somehow. I felt good. I sometimes rebelled when there were discussions about who is a Jew or who could be a Jew. “I’m a Jew, whats the problem? I don’t know about certain things, but I do know that I’m a Jew”. However, I didn’t know about a lot of things. From home, I knew how to prepare a seder. My collision with the cuisine at the university hall of residence was bizarre. I didn’t know the principles of kashrut, but I did know that I couldn’t drink milk after meat because it would make me ill, and that stuck with me.

I began travelling to Rychwałd on account of my son, so that he would learn more than I could teach him, and now he’s centuries ahead of me when it concerns knowledge. And with him, it was as I described. When did I start speaking to him about his heritage? From kindergarten. He returned from kindergarten one day with this huge piece of knowledge, “Mum, tomorrow we won’t cook meat. We’ll go to church and the priest will sprinkle ashes on our heads.”

I said, “Kubuś, sit down, let’s talk. I don’t have to cook meat, we can have days without meat. You know, I don’t go to a church. Your dad will come, hell take you.”

“Why don’t you go?” he asked. I replied, “Because I’m Jewish”, to which he responded, “Is it only you?”

So, I started naming all of my acquaintances whom he had around him, whom he knew. We’d never spoken before on that subject. Later, when I would speak with anyone on the street, he would ask, “Do they know that we’re Jewish?

So I don’t really know how he sensed those things about which it wasn’t necessary to speak too loudly. He began to feel more and more comfortable about it, but when he was in second grade at school, the question was asked again, “When do we go to communion and in which church?” So, again, I had an issue to deal with. Until one day, he said that he wanted to be a real Jew, if he was already Jewish.

I asked, “And what, according to you, does it mean to be a real Jew?” He replied, “I want to be circumcised.”

That event took place when he was twelve years old, before his Bar Mitzvah. Due to the fact that I wanted to do at least one thing at the appropriate time, we went with Kuba to Kishinev where there was a yeshiva. Within the space of two months, he was prepared and had his Bar Mitzvah. Years later, however, he admitted that he was sad because it had not occurred in the presence of our friends. One day, Kuba came into contact with a group of Hassidim, among whom was a tzaddik. It was decided that Kuba should start going to a Jewish school. As a result, he found himself at the Lauder School in Warsaw. Now, he’s in a yeshiva in New York. Hes also studying psychology and teaching.

Thank you so much for the interview. I hope that one day we can do a sequel.

As well as being Chairperson of the Częstochowa branch of the TSKŻ, Halina is the mother of Yaakov Wasilewicz, whose story also appears in the “Lives and Legends” section of this website.

Like the TSKŻ itself, Halina was a true Jewish Częstochowa institution.

Sadly, she passed away suddenly on

29th January 2017

Webmaster’s Comment:

This interview, conducted on 15th October 2012, appeared originally, in Polish, on the Virtual Shtetl website of the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews.

Interviewer:

Piotr Kowalik

English translation:

Andrew Rajcher

It is reproduced here on this website with the POLIN Museum’s kind permission and also with the kind permission of Halina herself.

The Treblinka Extermination Camp

The Treblinka Extermination Camp

- Commemoration of 70th Anniversary of Treblinka Uprising (2nd August 2013)

Our World Society and its members feel a deep connection to this place – most of the Jews of Częstochowa and its surrounding areas, who perished during the Holocaust, were transported to the Treblinka extermination camp, this factory of death, and were never heard of again.

One Częstochowianin, Samuel Willenberg z”l (pic right), was the last survivor of the Treblinka extermination camp revolt which took place in August 1943. On 2nd August 2013, he was one of the honoured guests at the 70th anniversary commemorations of that revolt, together with our World Society President, Sigmund Rolat.

One Częstochowianin, Samuel Willenberg z”l (pic right), was the last survivor of the Treblinka extermination camp revolt which took place in August 1943. On 2nd August 2013, he was one of the honoured guests at the 70th anniversary commemorations of that revolt, together with our World Society President, Sigmund Rolat.

As well as the commemoration ceremony, a foundation stone was laid for the future Holocaust Education Centre to be located at the Treblinka extermination camp. Not surprisingly, Sigmund Rolat will be one of the major benefactors of this project.

Israeli architect, Orit Willenberg-Giladi, the late Samuel Willenberg’s daughter, will design the new Holocaust Education Centre.

The World Society gratefully acknowledges

and sincerely thanks

![]()

Telewizja Orion

and

Czarek Szymański

for permission to use the video

which appears on this page.

The Post-War Jewish Orphanage

The Post-War Jewish Orphanage

- located at ul. Krótka 23, Częstochowa

In November 1944, as Poland was in the process of being liberated from Nazi oppression, the Polish Committee of National Liberation established the Provisional Central Committee of Polish Jews. After Warsaw too was liberated, the Committee’s headquarters was moved to Warsaw and became the Central Committee of Jews in Poland (Centralny Komitet Żydów w Polsce – CKŻP).

One of the organisation’s aims was to provide care to children, particularly orphans, through the setting up of nurseries, kindergartens and orphanages. The CKŻP established a regional office in Częstochowa and, in 1945, it created a Jewish orphanage to take in children who had been orphaned, or semi-orphaned or who were awaiting the return of their parent(s) to claim them.

According to Liber Brener, Chairperson of the CKŻP in Częstochowa:

Children came from the camps and from bunkers. They came from their Polish carers and from convents. They came from having survived in the country, minding flocks of animals. There were those who had wandered from village to village, often in a poor physical, spiritual and emotional state. Several were severely disturbed, suffering from phobias. Some did not want to admit that they were Jewish. Some stole and were inclined to robbery. Children rescued from convents had adopted the Catholic faith and continued to secretly pray to the Virgin Mary, even once they were in the Jewish orphanage.

The new orphanage was set up in the building of the former Perec Workers Nursery School at ul. Krótka 23.

Following the pogrom in Kielce in 1946, Jews were worried that a similar event may occur in Częstochowa. Many Jews took up arms to stand guard over Jewish buildings, including that of the new Jewish orphanage.

The photographs above were provided by Helen Albert, daughter of Doba (Danuta) Ita Albert (nee Drezner). Danuta (whose picture as a young girl appears left) survived the War, thanks to the help of a Polish family.

The photographs above were provided by Helen Albert, daughter of Doba (Danuta) Ita Albert (nee Drezner). Danuta (whose picture as a young girl appears left) survived the War, thanks to the help of a Polish family.

Danuta was one of the children in the post-War Jewish orphanage.

Seventy years later, in 2014, she returned to Poland to meet and thank the family who saved her. More about that reunion can be read HERE.

SOURCES:

The Webmaster

thanks and acknowledges

the following for sources in

providing information for the

creation of this page:

DANUTA ITA ALBERT

(nee DREZNER)

and her daughter HELEN

Prof. Dr. hab. JERZY MIZGALSKI

THE POLISH RIGHTEOUS website

and KRZYSZTOF BIELAWSKI

THE JEWISH HISTORICAL INSTITUTE.

If anyone can provide more

information on, or additional

photographs of, the post-War

Jewish Orphanage in Częstochowa, please email the Webmaster

by clicking HERE

The Częstochowa Ghetto

The Częstochowa Ghetto

I. The Establishment of the Ghetto

The concept of enclosing the Jewish population in assigned districts became a reality after the Germans gave up such unrealistic plans as transportation to Madagascar.

In the Radom precinct, such districts were created relatively early. Indeed it was already possible to notice the first fruits of this German decision in the last months of 1940 (November – ghetto in Opocznie, December – ghetto in Tomaszów Mazowiecki). Having started only in the spring, by the summer of 1941 it had spread throughout the whole precinct.

In accordance with the general order of the Radom Lascha precinct boss, the biggest ghettoes were created in April 1941 – in Radom, Kielce and Częstochowa and smaller ones in Busk, Chmielnik, Ostrowiec, Rawa Mazowiecka, Starachowice, Nowe Miasto.

Already by 1939, the German authorities had created the new administrative districts of the Częstochowa region. As a result of these changes, the greater part of the Jewish population found themselves beyond Częstochowa on territory directly connected to the Third Reich. At that time, two towns – Krzepic and Kłobuck – had the biggest clusters of Jewish population in the whole administrative district. Jews who at that time, were living in areas of the new Reich apparently could remain – whilst the whole Polish population was to be transplanted to the General Government area.

However, SS Reichsfuhrer Himmler’s order (29/11/1939) that “Jews and Poles, who had been ordered to move from some area of the Reich to the GG and who despite this still remained in German Reich territory, were to be summarily shot”, caused an inflow of Jews into Częstochowa already by the beginning of 1940. Many of them also thought that they could adjust their lives to the change of location.

The German plan to exterminate Częstochowa’s Jewish population (and in other Polish towns) was based on the gradual preparation of the German “death machines” for the Final Solution.

In 1940, regulations were issued which became the legal basis for creating Jewish residential areas.

In Częstochowa, German preparatory work started at the beginning of 1941. Its goal was, as ordered by Stadthauptmann Wendler in March of that year, the creation of a Jewish residential district by 9th April.

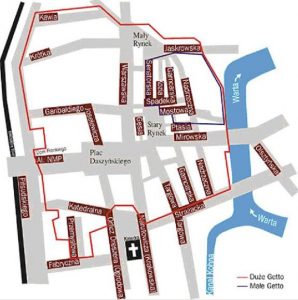

This order also specified the streets which were to be contained within this new adminstrative section of the town. The residential district to be enclosed extended around Daszynski Square, the Stary Rynek (Old Market) and the Warsaw Market. The railway line formed the boundary to the west; the Warta River to the east; to the north, ulicy Kawia, Kiedrzynska and Jaskrowska; and to the south, ulicy Fabryczna, Narutowicza and Strażacka. All Jews who lived outside this ghetto area were forced to move into the Jewish district by no later than 17th April 1941. At the same time, all Poles had to leave the area.

II. The “Big Ghetto”

This newly-created district was popularly known as the Big Ghetto. Its entrances were mainly guarded by OD-men, members of the Jewish police force. From the very beginning, the German authorities took extraordinary steps to isolate the ghetto inhabitants from the rest of the town.

Near the entrances to streets leading out of the ghetto were erected signs which warned Jews against leaving the district. They stated that leaving the ghetto without permission incurred the death penalty. Later, signs were also erected which threatened the death penalty to any Poles trying to enter the district. Black notices, on a yellow background, also warned of the risk of the contracting plague. The German authorities’ next move, by which they intended to hermetically isolate the ghetto, was to extract Katedralna and Strazacka Streets from the ghetto’s boundaries. In this way, the area of the ghetto became, on the one hand smaller and, on the other, considerably more densely populated.

It is difficult to determine the exact number of people living in the area of the ghetto. According to official statistical data, the number of Jews in Częstochowa at the time was around 40,000. In the summer preceding liquidation of the big ghetto, after the influx of Jews from the surrounding area, that number exceeded 50,000.

III. Extermination and Selections – The Liquidation of the “Big Ghetto”

After the Wannsee conference, the machinery was systematically prepared to serve one purpose – the extermination of European Jews. After all the organisational arrangements and the construction of the instruments of death in such camps as Auschwitz, Bełżeć, Majdanek, Treblinka or Sobibór had been completed, Himmler inspected them personally in the middle of July 1942. He then proceeded to the headquarters of “Operation Reinhard” in Lublin and discussed, with Globocnik, further plans for their genocidal activities in the General Government. As a result of these discussions, on 19th July 1942, he issued, from Lublin, secret orders to Wilhelm Krüger HSSPF in the General Government. That document determined 31st December 1942 as the beginning of cleansing the whole of the General Goverment of Jews

From that time, Jews only had the right to live in the so-called Stammlagern, i.e. collective camps located in Warsaw, Kraków, Częstochowa, Radom and Lublin. Only in specifically nominated places could selected Jews stay who were working for the requirements of the army.

In Częstochowa, preparations for extermination began prior to the events described above that had a more general scope. In June 1942, the Jewish Council (Judenrat) received, from the Stadthauptmann, an order to supply a precise new plan of the Jewish district with each individual home designated. They also nervously observed how the corners of homes and entrances to flats in cellars were being painted over with white paint. By the middle 1942, Jews were removed from a part of ul. Kawia, because there was to be established there a cemetery for future victims. Homes in ul. Garibaldiego were emptied to make room for future storehouses to contain plundered Jewish property.

The last stage of preparations to this final act of genocide was played out at the beginning of July 1942. The city authorities issued orders for a general roll call, designated for 3.00pm, at which all ghetto residents aged 16 to 60, from specified streets, were to be present – including members and associates of the Judenrat and the Jewish police. The order only excluded staff of the hospital within that region. As was later revealed, this entire exercise was a general trial exercise. prior to the planned September operation to liquidate the Big Ghetto of Częstochowa.

At 3.00am, 22nd September (on the Jewish holyday of Yom Kippur), the street lights were turned on, even though at that time, for reasons of economy they were dimmed at night to darkness. Jewish police units were summoned to immediately station themselves on the Metalurgia factory grounds at ul. Krótka 13. An hour later, with the police at the square, they received an order from the German officer in charge of the operation, for all residents from ulicy Kawia, Koszarowa, Krótka, Garibaldiego, Wilsona and Warszawsk, as well as parts of ulicy Garncarska and Nadrzeczna, to assemble by 6.00am in front of the factory.

They were required to bring with them their Work Card (Arbeitspass), in order to be checked by the German authorities. Shortly before 6.00am, panic broke out amongst those gathered. A group of forced labourers gathered near the exit of the ghetto. Herded from place to place by their guards and by soldiers in black uniforms, they attempted to move elsewhere. The first shots were fired, the first were wounded and killed. After a short time, the situation was brought under control. Soldiers from the Black Battalion slowly encircled the square. Methodically, they systematically finished off the wounded, even those who could still manage to stand and rejoin their companions.

After 6.00am, in ul. Krótka, a column of many thousands form. Women, men, children, the old and the young, the healthy and the sick – all wait with uncertainty for what fate will bring them. Nearly all hold their Arbeitspass. Each crosses the square where the selection happens – this takes several hours. Over 7,000 people were condemned to death. Around 350, thanks to their usefulness to the Third Reich armaments industry, would enjoy life for a while longer.

At midday, black-uniformed soldiers formed marching columns of five-abreast. Seven thousand people head towards the ghetto exit, crossing ul. Piłsudskiego in the direction of Zawódzie and only stop at the Częstochowa-Kielce railway line. A ramp had already been erected and a long train consisting of 60 cattle-wagons was waiting. An hour later, the doors to the wagons were closed and the train left in the direction of Treblinka.

On the ground, in puddles of blood, numerous corpses remain. At ul. Krótka 13, the square is cleaned. Numerous Jews gather approximately 200 bodies from the ground and, in wheelbarrows, cart them onto trucks. The bodies are then thrown into a large hole in ul. Kawia which had been prepared for the purpose earlier.

Further stages of this drama were played out on 25th-26th as well as 28th-29th September, barely a few days after the first “deportation”.

Subsequent operations take place faster and more easily than the first. Instead of gathering people as previously in the factory on ul. Krótka 13, specific blocks were combed by units of soldiers. The residents of designated homes were driven out into courtyards and, there, the final selection took place. The Germans informed members of the Judenrat that the deported Jews are bring taken to labour camps in Polish territory where they will work for the benefit of the Reich.

On 28th September, on the day prior to the third selection, green German police cars drive through the ghetto. Through megaphones, they announce that all Jews sent earlier by train had arrived safely at their destination, were feeling well and had commenced work. It was also officially broadcast that all Jews from the ghetto area, who were to assemble on the following day at the designated place, would receive half a kilogram of bread, marmalade and a bowl of warm soup.

That successful approach resulted in many hungry Jews reporting for selection of their own freewill on the 29th. This time, the authorities kept their word and distributed the promised food. However, there were many who did not believe the German authorities. These remain at home, but are removed from their homes amid screams and at gunpoint. During this third operation on 28th-29th September, the following streets were “cleansed”: Nadrzeczna, Garncarska, Targowa, Prosta and the Stary Rynek.

On 4th October, the next-to-last operation took place in the “Big Ghetto”. It encompassed, among others, “Dom Frankiego” on the corner of I Alei and ul. Wilsona, where the Germans, in April 1941, had housed the best Jewish artisans who were often forced to provide various services for the benefit of the Germans. (Jews called this building “The Artisan House”).

On that day, no more than 1,000 people were selected. A large number of ghettto residents, who had previously avoided being deported, were now caught, whereas earlier they had hidden in basements, in attics or behind fake walls in deserted apartments. The majority of those rounded up on 4th October were marched under guard to the train. With this transport, the last members of the Judenrat as well as half of the Jewish Police depart. The result of this Deportation Action was 40,000 Częstochowa Jews were transported to their deaths in Treblinka. The number killed on-the-spot was never accurately determined, but is estimated at around 2,000.

These specific operations actions were carried out on 22nd, 25th and 28th September, as well as 1st and 7th October 1942. The victims were transported by train to the camp at Treblinka.

In the Częstochowa area, the Germans left approximately 5,000 of the healthiest and strongest Jews alive, who were to be utilised for work in several factories, especially the HASAG munitions facfdtory, where several thousand Jews were forced to work.

V. The “Small Ghetto” – Częstochowa Forced Labour Camp

The Small Ghetto was created almost immediately following the deportations from the “Big Ghetto”. Approximately 5,200 Jews remained there – those who had survived the bloody events of the end of September and the beginning of October. They were squeezed into houses in a few streets which lay in the north-eastern section of the old Big Ghetto. The so-called Small Ghetto encompassed within its area ul. Koziaand parts of ulicy Nadrzeczna, Mostowa, Spadek and Garncarska.

|

It was located in one of the poorest and oldest districts of the city, long-inhabited by the city’s poor. All the houses in this area were small, toilets were mainly located in backyards and in many buildings there was a lack of running water. Only one street was asphalted, some were cobblestone, but most were covered in gravel.

The area of the “Small Ghetto” was surrounded by a barbed wire fence approximately 2 metres high. Houses located near the fence were emptied, as were the shops. |

The only exit from the ghetto was located at ul. Garncarska. Opposite the exit lay the Warsaw market to which, every morning, the Germans responsible for the work groups came in order to collect Jews who were designated for work.

In very centre of the ghetto, in ul. Garncarska, was the Jewish Police building and a small hospital. Officially, none of the Germans used the name Small Ghetto – in all German documents and noctices, the phrase Forced Labour Camp Częstochowa was used. It was only a matter of formality. The creation of a new Jewish residential district accompanied the “cleansing” of the old Big Ghetto. It took approximately two weeks.

At this time, the Germans concentrated their efforts on two types of operations.

The first of these was the gathering of property abandoned in Jewish homes.

In the big building at ul. Wilsona 20/22, which formerly had housed the Lewkowicz Furniture Factory, a large workshop was established.

From amongst the Jews, groups of trademen was chosen – painters, locksmiths, joiners, carpenters, electricians – who had the task of transforming one of the houses inul. Garibaldiego into a large warehouse.

The warehouse was divided into separate sections in which were later sorted clothing, shoes, furniture, lamps, sewing machines and type

writers, electrical appliances, sculptures, valuables and the like. This warehouse must have been huge as it was intended to contain the belongings of almost 50,000 people. The Germans also organised, from amongst the Jews, special groups called packers”. In the company of several German soldiers, each group drove through the streets of the former ghetto and loaded into the cars everything that had value which was found in the empty apartments.

The German soldiers’ other occupation was searching for Jews who were still hiding in the area of the old Big Ghetto. The city authorities – both civil and military – were aware that there were still many of them. The search for these Jews lasted practically the entire period during which the deportations occurred. The empty quarter was controlled by special patrols, after which they joined the next operation. In the initial period, soldiers of the Black Battalion” joined the Germans – later, the Germans did this alone.

(ul. Strażacka)

In the period after 7th October 1942, this task became easier. In the quiet, which prevailed in the houses and on the streets, it was easier to hear noises, rustlings, the cry of a child or coughing. Specially training dogs assisted the Germans in their task. They could sense a person hiding in a cellar, in an attic and even those hidden between double walls.

The majority of these people were discovered and shot on-the-spot or at the cemetery on ul. Kawia. There were also cases when the Germans were told about those hiding by other Jews who gave this information out of fear or under torture – or for the promise to allow the informer or his family to live.

Some hiding places had been prepared over several months, some had food stored within them to last up to two years and had access to running water. Unfortunately, the majority of these were discovered and the people who hid there were shot or deported to Treblinka.

The area of the Small Ghetto operated as a forced labour camp. Its inhabitants were subjected to life in barracks. Daily, columns of labourers proceded, under guard, to plants which lay outside the ghetto. A section of the Jews also worked in countless craftsmen’s workshops within the ghetto. The workers were not paid. For their labour, they received food ration cards – all numerically marked. Work commenced at 6.00am and was finished by 6.00pm.

V. The Final Liquidation

In January 1943, the Germans conducted further selections in the area of the Small Ghetto. The first of these took place on 4th January. That day, a police cordon encircled the entire ghetto area. Older people, women and children were principally singled out. The selection took place at the Warsaw Market. Its result was that approximately 350 people were sent to Treblinka, among whom were many children who had previously survived the pogrom in the Big Ghetto. That same day, during the course of the selection, a further 200 people were killed in the ghetto. They were later buried in the cemetery on ul. Kawia.

A further blow befell the inhabitants of the Small Ghetto in March 1943. The Germans advised the Council of Elders to prepare a list of people who had relatives abroad. Whispers spread that such people would be exchanged for Germans held captive in England. A fair number allowed themselves to be duped by this lie. On 20th March, many Jews gathered at the Warsaw Market square, ready for their promised departure. At the same time, the Germans issued an order for all remaining members of the Judenrat, doctors, engineers and the entire Jewish intelligencia to report to the square. When it was realised that this was, in fact, another selection, it was too late to turn back. The Germans had parked trucks on ul. Warsawska and loaded onto them the assembled prisoners. Under escort of armed soldiers, they were transported to the cemetery where a mass execution took place. Approximately 130 people were shot.

The policy of extermination was continued into April. On 23rd April, 25 Jews employed by the Ostbahn were killed. The Germans perpetrated this massacre after discovering a cell of the Jewish underground organisation operating within the station which had intended to carry out acts of sabotage on the trains. In June, bunkers and shelters of Jewish underground organisation members were uncovered in the Small Ghetto. This last discovery hastened the Germans’ liquidation operations in the Small Ghetto.

In the first half of June, approximately 50 people were murdered, including a leader of the Ghetto underground movement – a former Polish Army captain, Dr Adam Wolberg. However, the final tragic act in the ghetto played out during 23rd-26th June 1943. Over that period, cordons of various police formations surrounded the ghetto area.

The action commenced with the liquidation of bunkers belonging to fighters of the Jewish Fighting Organisation (ŻOB). The remaining few thousand ghetto inhabitants were gathered into the parade ground. They stood in the square for six hours waiting for the results of searches which

the Germans had commenced.

Accompanied by dogs, they penetrated underground the ghetto searching for bunkers. This operation was a major surprise for members of ŻOB (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa) such that they could not manage to camouflage the entrances to the bunkers or to hide themselves in time. Already by the ghetto gate, trucks were waiting. The Germans loaded a number of the fighters onto the trucks and into cars which drove off in the direction of the cemetery where they were executed – shot in the back of the head. The trucks made several such trips that day.

This time, the selection was carried differently – victims are not chosen individually, but by columns or rows. Again, the majority are the elderly, women and children. The sick in the hospital are killed where they lie. This “action” finishes in the late afternoon of 25th June. From 8th October 1942 to 25th June 1943, approximately 1,300 Small Ghetto inhabitants are murdered – aound 3,900 people remain alive. On 25th June, the remaining prisoners still standing on the parade ground were divided into smaller groups and transported to several factories in the Częstochowa area or in the vicinity: HASAG-Pelcery, Raków, Częstochowianka, Warta. They were to work there until January 1945 – with the quiet hope of survival.

The action in the Small Ghetto lasted almost a month. On 27th June, units of the army equipped with howitzers encircled the ghetto. Over many hours, shots are fired into the now empty buildings of the former Small Ghetto. The purpose of this was to scare those from the ruins who had, through some miracle, managed to avoid the fate of the others. On the following day, namely 28th June, German cars drive into the Ghetto area.

Through a megaphone, they announced that those who leave their hiding-places voluntarily will receive bread, marmalade and warm soup. They will also be included in an amnesty. The deadline to come forward was set as 30th June.

When the deadline had passed, it turned out that only a few Jews believed the promises of the Germans. On 1st July, soldiers enter the ghetto area covered with the ruins of homes. They find around 20 starving people – mainly elderly, women and children. They are then subjected to many hours’ interrogation, forced to reveal hiding places of other people or of valuables. After the interrogation, they are transported to the cemetery and shot.

Finally, on 20th July, minesweepers and explosives specialists enter the ghetto. Explosive charges are laid beneath houses. After a few hours, the Ghetto in Częstochowa is reduced to piles of rubble.

VI. Judenrat

The Judenrat was appointed on 16th September 1939 and had an identical role to that in other Jewish ghettoes. The Ghetto in Częstochowa was not an exception to the rule, so that the Jewish Council was an involuntary tool in the hands of the Germans. Through the Judenrat, the Germans squeezed high contributions from the Jewish populace. The Council was also obliged to meet quotas from the German authorities to provide workers for forced labour.

Firstly, in Częstochowa, a six-man representation was established for the Jewish population which was later replaced by a 24-man Council. Its Chairman was Leon Kopiński. By November 1939, the German authorities were already demanding of the Jews of Częstochowa contributions as high as 1 million złotych, for which a section of the Council members were detained as hostages. The amount of this contribution was eventually reduced to 400,000 złotych which could be paid off in instalments.

Over time, various offices were established within the Judenrat – commissions and departments such as the Labour Office, the Housing Office, the Requisitions Office, etc. The Council was composed of, among others, lawyers J.Gitler, Z.Rotbart and S.Pohorille; former athlete Bernard Kurland (as head of the Labour Office); former rector of the Jewish Gimnazjum Anisfelt (responsible for education); Kohlenbrenner (boss of the Housing Commission) as well as L. Bromberg and N. D .Berliner.

The Judenrat members, under the leadership of Kopiński, managed the ghetto day-to-day based upon German orders and regulations. They organised quotas of workers for forced labour, allocated newly-arrived Jews to apartments, collected contributions and provided meals for the poor and homeless. In 1942, when rumours spread through the Ghetto of proposed deportations, Council members travelled to Kraków and met with Hans Frank, delivering him a donation of 100,000 złotych in order to gain from him an assurance that no special operation was being prepared against the Jews of Częstochowa.

The Judenrat ceased to exist, in practical terms, in October 1942 following the liquidation of the Big Ghetto. Council members were among the last to be transported to Treblinka along with the entire Jewish Police. Council Chairman, Leon Kopiński, was shot on-the-spot on the charge of being disloyal to the German authorities. The only one who remained and who managed to live for a few more months was Bernard Kurland.

The Jewish Council was also responsible for the Jewish police in the ghetto. At its maximum in 1942, the Jewish Police numbered aound 250 people. Its first Commanding Officer was Maurycy Galster, but he was removed by the Germans after a short time. The task of organising the police fell to Anisfelt. He interviewed candidates with the aid of two other brigade members , and sometimes with the support of Kurland and Kopiński. The second Commanding Officer of police was a man by the name of Parasol – a former non-commissioned officer in the Polish army. Auerbach, a former Polish army officer and a certain lawyer became his closest associates.

Sources:

Text Author:

Radosław Butryński

His website is:

www.dws-xip.pl

We thank him sincerely

for his kind permission to

to reproduce his article here.

(The original text was translated

into English by Andrew Rajcher)

Photographs:

Many of the photographs

on this page come from a

discarded album found, in

Regensberg in 1945, by an

American soldier who was

serving in Company B, of the

56th Armoured Engineer

Battalion. The album had

belonged to a German soldier.

The album and its contants

were donated to the United

States Holocaust Memorial

Museum in Washington DC.

Our thanks to Dotty Grimes,

that US soldier’s daughter,

for this information.

"The Surviving Jews in Częstochowa"

"The Surviving Jews in Czestochowa"

- published shortly after the end of World War II

Shortly after the conclusion of World War II, the World Jewish Congress published a booklet entitled

“The Surviving Jews in Częstochowa”

based on lists supplied to it, at that time, by the Central Jewish Committee in Poland.

Please be aware that the listing is not strictly alphabetical.

Searching the Częstochowa Archives

Searching the Częstochowa Archives

Whether you are tracing your family history, conducting some genealogical research or obtaining the necessary information to claim your right to Polish citizenship, you can now obtain records from the Częstochowa Municipal Archives with the help of staff and students at the Jan Długosz University in Częstochowa.

Dr Julia Dziwoki (pic left) is an archivist and lecturer in the Department of Historical Methodology and Archives in the Faculty of Philology and History of the Jan Długosz University.

Within the University, Dr Dziwoki has now established the Centre for the Genealogical Research of Częstochowa Jews.

Together with her students, her Centre can create a genealogical tree of your family or simply search the archives for birth, wedding and/or death certificates of your family’s Częstochowa ancestors.

To take advantage of the wonderful service, email whatever information you have regarding family members (first names, family name, dates, etc.) to Dr Dziwoki at: jldziwoki@gmail.com