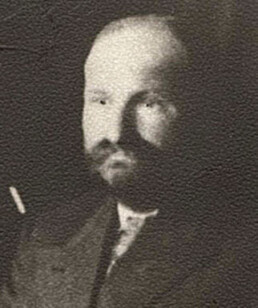

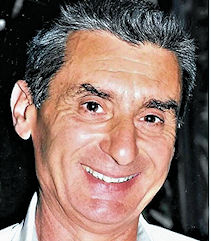

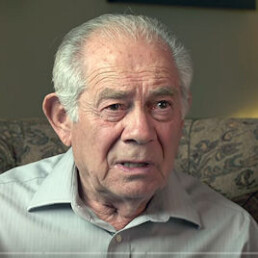

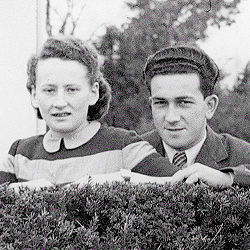

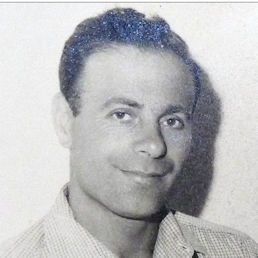

Machel Birencwajg

Machel Birencwajg

- craftsman, head of the Möbellager and a leader of the Jewish underground

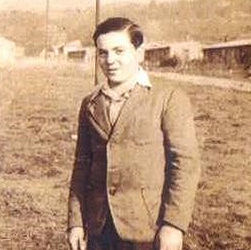

Machel Michał Birencwajg was born on 10th July 1907 in Częstochowa, the son of Icek Majer and Bajla née Kurnendz. He was a craftsman, communist and leader of the Jewish underground.

Machel Michał Birencwajg was born on 10th July 1907 in Częstochowa, the son of Icek Majer and Bajla née Kurnendz. He was a craftsman, communist and leader of the Jewish underground.

He received a traditional Jewish education in a cheder, after which he studied at the Jewish Gimnazjum. There, he joined the Zionist circle and was also a member of the Ha’Shomer Ha’Tzair scouting movement, as did his elder brother Pinchas and sister Mania (Ruchla). Machel was a charismatic, daring young man, full of energy and an accomplished skier. Very soon, he came to doubt the Zionist ideal and joined the illegal Communist Party

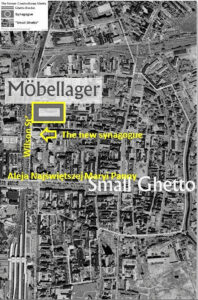

One of the most important forced labor camps in Częstochowa, during the German occupation of WW II, was the Möbellager (furniture warehouse) (ML) located at ul. Wilsona 20-22. It was on the outer edge of the ghetto, while the other side faced the “Aryan” part of the city. The grounds, spreading over two large yards, with storage facilities, belonged to Lewkowicz before the war, and Wajsberg also had his factory there. The Möbellager grounds were under the jurisdiction of the City of Częstochowa and Mayor Linderman assigned its supervision to Paul Lange.

Lange was a soft-spoken man and, amongst the few children in the Möbellager, they referred to him, “Those wearing a brown uniform they are nice guys, but those in a black uniform, oh boy, they are mean. He was nicknamed “Chazn”.

After the mass deportations to Treblinka, starting 22nd September 1942, almost all children his age had disappeared from the streets of Częstochowa. For this age group, the city had become  essentially “Judenrein”.

essentially “Judenrein”.

There was a rumor in the Möbellager that Lange, certainly, knew all the time about the “bunkers”, where mothers with their children were hiding, but probably for his own security he withheld his secret.

Lange would spend his days bored in his office. When he learned about Machel Birencwaig’s popularity among his fellow workers, he entrusted him with the management of the Möbellager. In essence, Machel became the Möbellager’s CEO much to the relief of Lange who, from time to time, could leave the city on a bird hunting spree.

Machel’s popularity reached outside the bounds of the Möbellager – people in the ghetto nicknamed the Möbellager the “Machel Lager”.

Lange’s decision, to hand over full powers to Machel, was a gift of Providence, as it gave Machel and his colleagues the opportunity to save many lives from the hands of the murderers. During the deportation of the Jewish population from the ghetto (in September and October 1942), Birencwajg and his companions saved hundreds of Jews and hid them in the Möbellager.

Following the opening of the “Small Ghetto”, they were smuggled there, despite the presence of Germans and two Jewish spies (“Kulibajki” and Gnata), who were specifically sent by the Gestapo. These activities were made possible due to Birencwajg’s determination and mental resilience. (Mothers, with their children, were transported inside wardrobes, sofas, and chests, and were hidden in shelters prepared by the underground.)

Workshops were built in the Möbellager, which employed professional Jewish tradesmen in many areas of competence – carpenters, locksmiths, electricians, sanitary specialists, automobile mechanics, painters, upholsterers, curtain decorators, etc.

When Machel took over, sixty craftsmen worked there but, following the 22nd September to 4th October 1942 deportations, when 40,000 people were sent to the Treblinka death camp, he negotiated with Mayor Linderman for more help, and their numbers soon doubled. They then called in the rest of their families from the ghetto, and the number grew to around 400.

After the deportations, teams of workers were sent out from the Möbellager to the ghetto, which had turned into a ghost town, to collect furniture and valuables from the now empty homes. This mission was assigned to Machel Birencwajg.

Carl Langner writes:

“One day, Machel learned that there was still a family hiding at Aleja 10. He sent a group, comprising his brother Pinchas and his cousin Jankev (Mojs) Rajch, to get them. They took a horse-driven platform charged with furniture and machines, found the family and smuggled them. The children were hidden in sacks surrounded with machines. On the way back to the Möbellager, they had to pass through German and Ukrainian control stations. One of them was corrupt, but another was not. They all risked immediate death if anything was uncovered.“

However, perhaps the most spectacular rescue occurred on that fateful Yom Kippur on 22nd September 1942, when the first “Akcja” took place, and a few thousand of the “selected” were sent to the Treblinka death camp. The route to the Umschlagplatz, the train station near the Warta River, led along ul Wilsona. As the crowd was passing the Möbellager, Machel and a group of workers, in a daring and heroic move, taking advantage of the turmoil, somehow distracted the Schutzpolitzei guards away from the gate. When the terrorised and panicked crowd of elderly people and mothers with their children came near, many rushed inside the open gate. Up to six hundred people were saved that day.

When the “Small Ghetto” was opened in November 1942, Hauptman Paul Dagenhardt ordered the Möbellager workers to move to there and live at ul Nadrzeczna 88. Immediately, Machel had them build there four new “bunkers”. This was important, as it allowed the transfer of the elderly and the children, when the “bunkers” in the Möbellager became too crowded. At the beginning of November, a large number of children were sent there.

One such smuggling is described by Leber Brener:

“Children were hidden in coal crates, furniture or wrapped in old clothes. The horse-driven cart was also loaded with a large pile of old clothes. At the entrance to the gate, Machel ordered the bundles of clothes to be unloaded and, while the guards were busy checking their content, Machel whipped the horse and the cart, with the children, rushed inside. This maneuver required steel nerves, and Machel was the man.

A detailed account of the activities in the Möbellager, and the role of Machel Birencwajg, is also provided in the testimony of Leon Silberstein:

“At that time, there was already a Möbellager for the plundered Jewish furniture. It was headed by Machel Birencwajg, who played an important role. My group also worked there.

“When furniture was brought inside the Möbellager, some Jews were also smuggled inside, especially children and elderly people, that is, those who were not able to work and risked being shot dead. Such people were brought in inside cupboards and we drove them inside the Möbellager. That is how we successfully saved a large number of children and elderly people, who for sure, would have been selected during an ‘Akcje’.”

At all times, Machel was in contact with the underground in the ghetto and was a key man of ŻOB (Jewish underground movement).

Clandestine activities, crucial for the underground, were carried out in the Möbellager. False identity cards (Kenkarte) were printed allowing people to escape to the “Aryan side”. Hand grenade parts were made there and, later, assembled in the “Small Ghetto” under the guidance of Heniek Wiernik. Some of these grenades had been smuggled out and sent to the Warsaw Ghetto, where they were used against the Germans during the 19th April 1943 uprising.

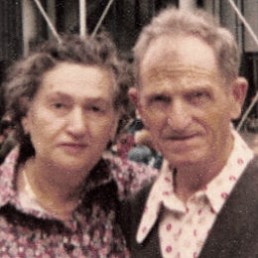

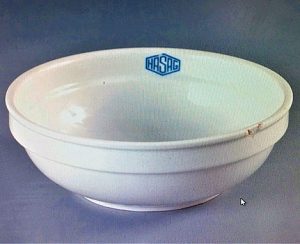

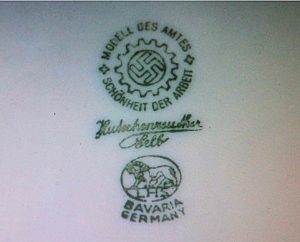

Living conditions in the Möbellager were not as drastic as in other forced labor camps, such as in the HASAG camps outside of the city. Nevertheless, food was rationed and every workshop worker received his meager daily portion. This posed a problem for the families hiding in the “bunkers”, since they were clandestine residents. It became even more critical after the 22nd September 1942 deportations, when a large number of people unexpectedly flocked into the Möbellager and Machel had to build new “bunkers” for them. Thus, after a hard day’s work, and waiting for darkness to fall, Machel and his elder brother Pinchas went from “bunker” to “bunker” and gave away a part of their food portion to those hiding, brought them fresh water and carried away their waste.

On the 8th June 1943, Hauptmann Paul Degenhardt, with his Schutzpolitzei, having been tipped by a Jewish informer, burst inside the Möbellager aiming to liquidate it. He shouted out an order to get Machel and his family. Machel quickly realised that he was in danger, and ran to the second yard to hide. “They’ll never get me alive”, he said to colleagues as he fled.

During their search, they found his 72-year-old mother Bajla, hiding in a public toilet in the second yard. They beat her cruelly, so she would reveal Machel’s whereabouts. People in the first yard heard her screaming “Bitte nicht schiessen, nicht schiessen”, as she desperately pleaded for her life – Degenhardt killed her.

They then found Machel’s wife, Hadassah (Hania) nee Feldman. They took her to the Zawodzie prison from where she was later taken to the Jewish cemetery and was murdered there together with friends.

Pinchas, with others, was standing in a row, while the search continued. He was eating his new Kenkarte with the Aryan name “Piotr Stanislawski” and trying to swallow it. If ever they had found that ID card, they would shoot him dead on the spot. A Schutzpolitzei officer came near and asked him about Machel, and punching him in the face and breaking his teeth. He then pulled out his gun, pointed it diretly at him, but he did not pull the trigger, saying, with a waive of his hand, “Ach, du kommst so wie so Um”, (You will perish anyway.). He put the pistol back into his holster. Pinchas was taken to the Gestapo. At night, he jumped out of the first floor window onto the top of a tree below and ran to hide in the “Small Ghetto”.

Colleagues decided that Machel would now be safest outside of the Möbellager. So they resorted to a well-tested technique – they smuggled him out inside an empty cupboard in a horse-driven cart. As they approached the gate, Machel shouted to friends below, “Ratujcie się, ratujcie się !” (“Save yourselves! Save Yourselves!”). He somehow felt that he would never see them again.

He went into hiding on the “Aryan side” of the city, in the apartment of a Pole whom he knew and trusted. This young man, ever since he was a teenager, worked for many years at the Birencwajg’s store and workshop on Aleja 10. He earned a decent living and was able to provide for his family. Soon after, however, he blackmailed Machel by asking him for money. At one point, Machel summoned Leon Zylbersztajn to bring him some jewellery to satisfy the Pole’s demands.

Even in such a desperate situation, the odds had been in Machel’s favour. He had a Kenkarte with a fake Polish name, allowing him to travel outside of the ghetto. He did not look Jewish, and he spoke and wrote Polish like a a non-Jew. Moreover, he underwent surgery so as to mask his circumcision. He could have easily survived the war, just like his cousin Jankev (Mojs) Rajch and Berek Wajsberg, who both fled to Switzerland and survived . But he stubbornly refused, saying that he would not abandon his beloved. So, he waited, hoping to get a chance to deliver Hadassah from the hands of the Gestapo.

On the 19th of June, a dramatic graffiti from ŻOB appeared on a wall in the ghetto. The scribbled words said, “MACHLA NIEMA , MÖBELLAGER DD, ODCIĘCI DN 19.VI.43”, meaning, “Machel cannot be found, the Möbellager is finished. We are cut off”, followed by the date above. Sometime later (date unknown), two Schutzwerk Politzei broke into the apartment of the Pole. They pulled Machel foutrom under a bed and took him to the Gestapo.

Machel was tortured. As a member of ŻOB, he took orders directly from Mojtek Zylberberg, and knew the names and the hideouts of colleagues, and the caches of weapons and money. Inmates saw him being brought back into his cell unconscious. On the 29th of July, Machel and several inmates, were loaded onto a truck, driven to the Częstochowa Jewish Cemetery and ordered to undress, as was the rule. A supreme humiliation. Machel refused and was cruelly beaten before he was shot dead.

Webmaster’s Comment:

The text on this page was prepared by

Mark Stanislawski-Birencwajg

– Machel Birencwajg’s nephew

and

Wiesław Paszkowski

– historian of the

Częstochowa Historical

Documentation Centre

Mark Birencwajg’s Story

At the time of the liquidation of the ghetto in September 1942, Mark was five-years-old and, together with a group of children, hid in the Möbellager.

One day, in the winter of 1942, he was with his grandmother Bajla, sitting next to the warm stove, when a man suddenly opened the kitchen door from the outside yard. His grandmother instinctively threw herself against him in order to protect him with her body. It was Lange, the Möbellager supervisor. He stood at the entrance showing his sore finger. Bajla went over and treated him with iodine and a band aid.

When the situation became dangerous, with the intention of saving him, Mark’s parents gave him to a Polish family.

Częstochowa Jews Under Communist Rule

Częstochowa Jews Under Communist Rule

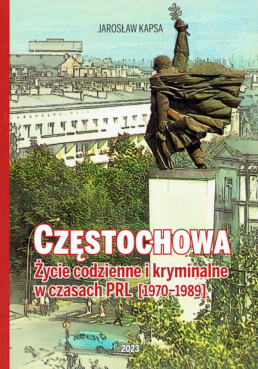

- an extract from "Częstochowa - Everyday and Criminal Life During the Polish People's Republic"

The following is an extract (pp. 72-75) from

“Częstochowa – Życie codzienne i kryminalne w czasach PRL (1970-1989)”,

by Jarosław Kapsa.

It was published in 2023

by Towarzystwo Galeria Literacka, Częstochowa.

This extract is published here with the author’s kind permission.

It has been translated into English by Andrew Rajcher.

People from national minorities were treated as suspicious. March 1968 showed that being a Jew, in the Polish People’s Republic, meant being suspected of being hostile towards the state. Sad testimony to this was the marginalisation of Częstochowa Jews.

After 1956, there was a revival of activity of the Częstochowa [branch of the] Cultural-Social Association of Jews [TSKŻ], with its headquarters in its building at ul. Jasnogórska 36. The Jewish Religious Congregation was also recreated in the building, which also held the ritual bath (mikvah), on ul. Garibaldiego.

The TSKŻ had 168 registered members, with Waksman as its chairman. It distributed 5,000-15,000 zł annually in aid to war victims. It organised cultural presentations. Excursions and summer camps were organised for the children, with social care provided by Dr. Bronisław Rozenowicz. The most active within the TSKŻ were Maurycy Baum, deputy director of “Papierni”, his wife Ewa, the Horończyk couple, Szymon Jesionowicz, Szymon Grunbaum (the famous furrier), the Prokurowski family and Tadeusz Altman (FJN activist).

The Jewish Religious Congregation had 23 members, including Helena Baum, Seweryn Dresler, the Kromołowski family and the Landman family.

This TSKŻ branch was one of the most active in the Katowice Province. In 1964, a youth congress was organised at the TSKŻ premises. Young people came from Katowice, Gliwice Myszków and Bielsko-Biala. It was accompanied by a music competition for bands and soloists. First place went to Alfred Pacanowski from Częstochowa.

In 1964, Stefan Laufer became the new chairman, vice-chairman Horończyk, secretary Leon Frank and treasurer Samuel Ajon. Those elected to the board of management were Dawid Albert, Henryk Grunbaum, Maria Klajn, Leon Hercberg, Chaim Segal, Ewa Baum and Liliana Romanczuk. Cultural, social and cemetery committees were established. There were 151 members and assistance was provided to 98 families (262 people).

A general meeting of the TSKŻ branch was held on 23rd January 1966, with the participation of 51 members, in the presence of the representative of the Municipal Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party [KM PZPR] Zygmunt Sobczyk and the head of the Department of Internal Affairs Zygmunt Marszałek. Motions were passed regarding the punishment of the ghetto executioner Degenhardt, the erection of a monument honouring the victims of the ghetto and the naming of a street in honour of Józef Lewartowski (pre-war Zionist left and KPP activist, co-founder of the Polish Workers’ Party and an organiser of the Warsaw ghetto resistance movement. He was killed in the April 1943 uprising.).

The board’s decision to hand over, to the city authorities, the property containing the ruins of the [New] Synagogue, for the construction of the Philharmonic Hall, was silently accepted.

In 1967, following the reaction of the USSR authorities to the war in Israel, the Częstochowa SB [Służba Bezpieczeństwa – Security Service] received, from the Ministry of the Interior, instructions on Zionism, background studies and an order to search for people who were hostile to the government or who had contacts with foreign countries.

Saturnin Limbach and Alfred Czarnota were identified as being among those maintaining contact with Israel. According to the SB, hostile views were expressed by Samuel Ajon – at a meeting of the KM PZPR, he criticised Laufer and distributed a book about the Jews in Częstochowa. It was noted that Warsaw University student, Ignacy Pacanowski, had submitted an application to go to Israel. Henryk Grynbaum had distributed texts in Hebrew. Alfred Kromołowski, a lawyer, had defended an injured Jewish woman and Zomersztajn, a rich man, had been convicted of currency trading.

In total, fifteen people left Częstochowa in 1968. In 1969, five families left, as did one individual, Helena, the daughter of Alfred Kromołowski. At the end of 1969, 182 people, who were identified as Jews by the SB, remained in Częstochowa. Of this group, twenty-eight tried to leave.

In 1969, the Jewish Religious Congregation had fifty members. Its chairman, Jakub Laderman left, as did his successor Leon Stawik. The [Czestochowa branch of the] TSKŻ had seventy members, but almost no one came to the meetings – its activists “sat on their suitcases”. As part of its surveillance, the SB established four evidentiary files and planned another four against “enemies”, including Zdzisław Skorupski, Dorota Hasenfeld and Tadeusz Unglik.

After 1970, the TSKŻ resumed its activities, with seventy people confirming their membership. Amongst them, the SB identified enemies and people who supported Israel – among them being Alfred Kromołowski, Ignacy Wajman, Bolesław Piętos and Jacek Zomersztejn. By a decision, on 31st December 1969, of the Department of Internal Affairs (WRN), the TSKŻ’s premises at ul. Jasnogórska 36 (now Help Centre for Disabled Children and Their Families) was expropriated, while allowing them to occupy another premises temporarily.

The Congregation found itself in an even more difficult situation. Fulfilling its religious function required having rooms for a synagogue and a ritual bath (mikvah). Following the expansion of its plant, the Steelworks [Huta] became located in the immediate vicinity of the Jewish cemetery.

In 1970, a development plan for the Steelworks was adopted, which included the cemetery within the Steelworks’ terrain. New burials were formally banned and it was decided to liquidate the burial site, allowing those interested to exhume and move the bodies of their loved ones.

This evoked a protest from amongst Jews, not only from Częstochowa. The Częstochowa cemetery was one of the largest [Jewish cemeteries] in Poland. In the Jewish faith, these places are sacred. They contained the graves of tzaddikim, which were visited by their followers from all over the world. The activity of the Częstochowa Congregation resulted in the wife of the Satmar chief rabbi, Faige Teitelbaum, becoming involved in the defence of the cemetery. The Chief Rabbi of Poland protested as did Jewish families from Kraków and other cities.

Despite the level of international protests, the authorities remained adamant. Some of the families concerned accepted the fate [of the cemetery]. According to the publication “Rzemieślnik” [“The Craftsman”], dated 21st April 1971, at the cemetery, the body of the tzaddik, the Gaon, was exhumed by the Szapiro family and the remains were transported to the USA. Other exhumations were also sporadically carried out. After the Holocaust, most of those buried there had no living family members and so there was no one to care for their final resting place.

Under pressure from the Jewish Congregation, the management of the Steelworks agreed to a compromise solution. The cemetery was incorporated into the Steelworks’ terrain. Only the part intended for the construction of a railway line was to be liquidated. The oldest graves and memorial sites, located in the cemetery, would be fenced off and protected.

Information sent from Częstochowa, to the Ministry of the Interior on 23rd September 1970, conveyed information about the mood of the Częstochowa Jews, that they fear for their Congregation’s building at ul. Garibaldiego 18. Indeed, the municipal authorities, without regard to any ownership right, had taken over occupancy decisions, introducing new tenants to occupy the building, without the knowledge or consent of the Congregation.

A note from the SB, dated 26th March 1971, advised that Jews, Majewska and S. Laufer, took part in a meeting of the KM PZPR, together with workers’ activists. This should not be surprising as Laufer was one of the founding fathers of the communist movement and, together with Majewska, was a member of the party’s authority. The SB’s information specifically highlighted his national origins {Jewish], when Laufer “aggressively attacked Feliks Kupniewicz, arrogantly attacking him of irregularities in the operation of a clinic, on ul. Kopernika, which treated party activists”.

Another SB note contains information about a teacher from Przybynów, a Jew, who criticised the party. People, who were applying for emigration, continued to be checked. Another note states that Janusz Archan, a Jew from Huta Stara, had bought a Fiat 125, had criticised the party and maintained contacts with the USA.

In 1973, only thirty-three families lived in Częstochowa whom the SB identified as Jewish. They continued to be treated as potential enemies of the Polish People’s Republic. Two separate cases were investigated.

Operation “Visitors” was regarding Leon Frank, born in 1899 in Częstochowa. He was retired. According to the SB, in 1975, Frank, as secretary of the TSKŻ, had received money from the TW. There is also information about personal conflicts in the Society’s board of management. The information about the dispute at the board meeting, on 16th August 1976, devoted to the preparation of the ceremony commemorating the anniversary of the “liberation of the ghetto”, is strange but, at the same time, it reflects the atmosphere of the times. Perhaps the official confused it with commemorating the “liberation of Częstochowa by the Soviet Army”. However, the effect was macabre – the liberation of the ghetto by the German army.

However, the dispute at the meeting was not about “liberation”. It was about the composition of the delegation that went to discuss, with the city authorities, the renovation of graves – places of national memory – at the cemetery. Ultimately, the delegation consisted of L. Frank, L. Stawik and S.Laufer.

In November 1976, a meeting of the Cultural Society of Częstochowa Jews was organised in Paris, according to the SB, at the initiative of Zionists. As Frank’s departure was blocked, Halina Wasilewicz, the TSKŻ’s new secretary, became the delegate. Unfortunately, she was also refused a passport. Ultimately, the SB’s efforts led to the elimination of Frank from the TSKŻ. He then submitted an application to go to Australia, Again, he was refused and, being ill, withdrew from public activity. He only asked authorities to allow his daughter Helena, a graduate of the University of Technology, to travel.

The second case was operation “Prezes”. It concerned TSKŻ branch president L. Stawik, who was born in 1911 in Warsaw and lived at ul. Garibaldiego 10. He was described as being uncompromising regarding the matter of moving the cemetery. Together with Leon Gongol from the USA, he visited the Town Hall in 1977, protesting against further plans to liquidate the remains of the cemetery.

It was noted that he had a son in the USA, Andrzej, and that he maintained contact with Zionists, obtained information and then disseminated it with the help of secret collaborators. Also that, while undergoing treatment in a sanitorium in Świnoujście and being influenced by his wife, he was baptised as a Catholic, which resulted in an atmosphere of distrust within the Jewish community and in Stawik’s social isolation.

The destruction of the few Częstochowa Jews, who remained after the Holocaust and the March [1968] riots, is a terrifying and, at the same time, shamefully hidden episode from the 1970s. If it were not for documents preserved in the archives of the IPN [Institute of National Remembrance], no one would have suspected that such a liberalising system was committing actions with such a nationalist tradition.

Perhaps it was a rational explanation for counteracting ideological enemies – clerics, supporters of national ideals, Social Democrats whose origins lay in the PPS and, even, disappointed Communists. In this case, however, the only criterion being considered was nationality. The enemy was both the traditionally religious Frank and the communist activist Laufer.

Even people, who gave up their Jewishness and were fully assimilated into the Polish environment, such as A. Czarnota or the Hasenfeld couple, were included amongst the ranks of enemies. No amount of working for the benefit of the city protected anyone if they had “bad” origins. Surveillance and the destruction of the community was carried out by the SB on behalf of the Ministry of Internal Affairs [MSW]. This does not mean, however, that such actions did not have public support.

A symptom of the antisemitism of the 1970s was the careful erasure of Jews from the space of collective memory. The cemetery, within the terrain of the Steelworks, was not the only one to be damaged. As recorded within the SB records, the Religious Congregation demanded the preservation of the cemetery in Olsztyn near Częstochowa. Even today, we do not know where it was.

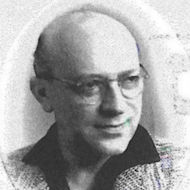

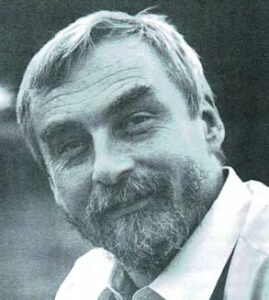

About the author:

Jarosław Kapsa (born 11th May 1958, Kraków) – writer, journalist, politician and local government official, former member of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland, opposition democracy activist.

He matriculated from the Mikołaj Kopernik High School in Częstochowa and graduated in history at the Śląsk University in Katowice (2010).

Under martial law, he was interned from 31st December 1981 until 13th December 1982. Following his release, he continued to be active within underground structures and worked with independent magazines, for which, in December 1985, he was again arrested – this time for a period of three months.

In 1989, he was elected to the Sejm. As a member of parliament, he was a member of the commission which investigated officers of the Security Service [SB] and also within the military secret services.

After withdrawing from political life in 1992, he took up journalism, working in “Zycie Warszawy”, “Życie Częstochowska” (deputy editor-in-chief), “Dziennik Częstochowski 24 Hours” and “Gazeta Częstochowska”. Since 2004, he has been a regular columnist in the regional weekly “7 Dni” and has worked with the Częstochowa Literary Magazine “Galeria”. Since 2002, he has been employed at the Częstochowa Town Hall.

In 1986, his radio play won an award in a Radio Free Europe competition and, in 1989, the Polcul Foundation recognised his journalistic activities.

His other awards include Medal of Merit as a Cultural Activist (2000), the Officer’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta (2011) and the Cross of Freedom and Solidarity (2015).

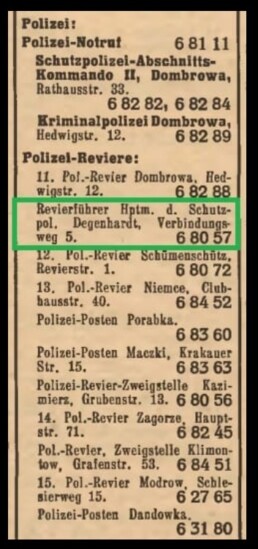

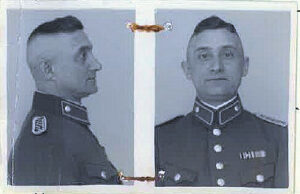

Hauptmann Paul Degenhardt

Hauptmann Paul Degenhardt

"The Lord of Life and Death" in Częstochowa

In the spring of 1942, Hauptmann Paul Degenhardt was transferred from Sosnowiec to Częstochowa, where he took command of the Schutzpolizei – the uniformed German Police Force. He remained in that position until the end of 1943, when he was transferred to the staff of the commander of the Ordungspolizei, in Corinth Greece, to combat local partisans.

The police department in Częstochowa, which Degenhardt took over, initially comprised 30-40 German officers. It was reinforced to 50-60 men by the summer of 1942. Over time, the name of this command was changed to the Schutzpolizeikommando (“Protection Police Command”). Its area of responsibility corresponded to that of a comparable agency within the Reich.

During his time in Częstochowa, he oversaw the “resettlements”, from 22nd September until mid October 1942, during which over 40,000 Jews were transported, by train, to their deaths at the Treblinka extermination camp.

During each selection for “resettlement”, with his riding crop in hand, Degenhardt would indicate to the left or the right – left meant death, right meant “able to work” and a little longer to live.

Degenhardt also oversaw the liquidation of the “Big Ghetto” and the creation of the “Small Ghetto”. He then also oversaw the liquidation of the “Small Ghetto” and the transfer of remaining survivors into barracks of the slave labour camps.

During that time, he also committed, or ordered to be committed, the murders of individual Jews, for which he stood trial in the Lüneburg District Court (Germany), beginning on 29th December 1965. On 25th May 1966, he was found guilty of twenty-eight charges of murder (involving seventy-one victims) and was sentenced to life imprisonment.

He served seven years in prison and was released on health grounds. He died not long afterwards.

CLICK ON EACH HEADING BELOW TO VIEW DETAILS

Paul Degenhardt, was born, on 5th January 1895, in Landeshut/Schlesien, into a large family of roofers. He and his five siblings were mainly raised by their mother (Anna nee Wit), as their father died in as work accident at the turn of the century.

He attended elementary school and then began work in a silk weaving plant where, through self-study, he became a pattern draughtsman.

In August 1914, he volunteered as a soldier. During the First World War, he was deployed on the Eastern Front and was twice slightly wounded by grazing shots. Following the end of the war, he joined the Freikorps, fighting in the east.

In November 1919, he joined the Sicherheitspolizei [Security Police] in Breslau. In 1920, after attending a police academy, he came to Oels and, after having worked in various commandos in Kreuzberg and Gleiwitz and taking part in other courses, he became a police sergeant in 1927.

On 23rd February 1931, in Gleiwitz, he married Charlotte Arn. They had three adult daughters came from this marriage. A son died soon after birth.

On 1st September 1932, Degenhardt became a member of the National Socialist Party – Membership No.: 1,330,601.

In the following years, he became actively involved in the party. In 1932-1934, he also belonged to the S.A. In 1938, as police chief, when he took over the local police station in Ackerfelde, he also became that town”s local NSDAP group leader.

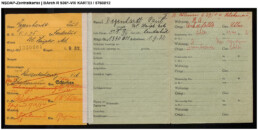

Ref: R 70 POLEN – 908

Ref: R 70 POLEN – 908

It is believed that this is Degenhardt’s civil service personnel file and that he appears in a policeman’s uniform..

It shows that he was married on 25th February 1931 and subsequently had four children, one of whom died after one day.

More details are shown in the English-language translation of this document.

On 1st June 1940, Degenhardt joined the general SS and, having been promoted to lieutenant in the Security Police, he immediately received the rank of SS-Untersturmführer. Around this time, for official reasons, he needed to change his place residence several times.

At the end of 1941 or the beginning of 1942, on 19th January 1941, he became an SS-Obersturmführer and, at about the same time, he was promoted to SS-Hauptsturmführer.

In the spring of 1942, Degenhardt was moved from Sosnowiec to Częstochowa, where he commanded the local police – taking over from Hauptmann Heutz, who was not a member of the SS. He remained in command there until the autumn of 1943.

During that time, he oversaw the deportation of over 40,000 Jews from Częstochowa to the Treblinka death camp. He also oversaw the creation and the liquidation of the Częstochowa “Small Ghetto”.

While in Częstochowa, he committed, or ordered to be committed, numerous murders. which are described in detail in the court verdict (the transcript of which appears on this page in both the original German and the English translation). In 1966, he was convicted on twenty-eight charges of murdering seventy-one Jews.

After leaving Częstochowa, Degenhardt returned to Sosnowiec for a short time – to the police headquarters, which had been established there in the meantime.

At the end of 1943, he was then transferred to the staff of the commander of the Ordnungspolizei in Corinth. One of his responsibilities there was to fight partisans.

When the Front was receding, he returned, via Vienna, to what was then Reich territory and ended up in northern Germany.

In April 1945, on the Elbe, he was taken prisoner-of-war by the Soviets – but he was soon able to escape. Shortly after, near Ludwigslust, Degenhardt was picked up by English troops, but escaped again

With “any” papers which he had been able to get hold of along the way, he went to Leipzig, where his brother-in-law gave him civilian clothes. He then made his way to Silesia [Pol: Śląsk], where he was arrested by Polish militiamen and was imprisoned in Ratibor [Pol: Racibórz].

After fleeing again, he took a job with a farmer in Thuringia, but then moved west, when American troops evacuated Thuringia. In Regensburg, he had papers issued in the name of his father-in-law and, as a construction worker, worked there and in the surrounding area. He then joined a refugee transport heading to Upper Bavaria and, still under a false name, worked as a farm hand until 1950.

Around this time, he found out that there was a police officer, living in Celle, who knew him from previous joint official activities before the war. Degenhardt went to see him – it was Hauptkommissar [Chief Inspector] Galonska. He told him that he had recently been released from Polish captivity. After Galonska confirmed his identity, he had the correct papers issued again. He remained in Celle, working in various jobs. From Celle, he again got in touch with his family, who had found shelter in the Ore Mountains.

Together with them, in 1951, he moved into an apartment in Unterlüss.

At the end of 1951, for the first time, Degenhardt showed signs of a mental disorder. He was admitted to the Lower Saxony State Hospital in Lüneburg by decision, on 18th November 1955, of the Celle District Court .

The medical officer’s report, dated 17th November 1955, contained the diagnosis that he was suffering from increasing mental and physical restlessness, which had increased to nocturnal “wanderlust” and that, according to his own statements, he was hearing voices that he had heard from his earlier experiences in fighting against partisans.

In addition, the medical officer had found an injury on Degenhardt, the result from an attempted suicide.

However, a final decision on his accommodation was not made, as Degenhardt agreed to remain in the hospital voluntarily. The “final improvement”, when he was released on 7th January 1956, did not last. On the advice of his family doctor, he returned to the Lüneburg State Hospital.

From there, on 7th July 1956, he was released as largely improved.

[Webmaster: There are opinions that Degenhardt was feigning illness in order to avoid prosecution.]

Almost three years later, namely on 11th May 1959, for a third time, Degenhardt entered the Lüneburg State Hospital for treatment of an “endogenous psychosis”.

It was here, on 14th December 1959, that an arrest warrant, dated 9th December 1959, was executed.

He was suspected of being an accessory to murder. Pre-trial detention was ordered to be carried out in the State Hospital because of Degenhardt’s state of health.

Another arrest warrant was issued, on 23rd October 1963, by an investigating judge of the Lüneburg District Court and was executed on Degenhardt on that day.

It was based on the suspicion of murder. It is believed that the delay, some four years, in issuing this warrant was due to the prosecution attempting to locate appropriate witnesses to the different charges.

The pre-trial detention was carried out on the basis of that warrant, after the first warrant was overturned by decision of the First Serious Crime Division of the Lüneburg District Court on 12th March 1965

According to the Lüneburg Public Prosecutor, after serving seven years in prison, due to his ailing health, Paul Degenhardt was freed by the Niedersachsen Minister-President – as an “act of mercy”.

[Webmaster: Ironic, since he showed no mercy towards his Jewish victims.]

On 24th May 1996, Degenhardt was sentenced to life imprisonment by the Lüneburger Schwurgericht (court) and was serving his sentence in the Strafvollzugsanstalt Celle [prison in Celle]. His health was already weak at the time of the trial.

He died not long after his release.

Acknowledgements:

The World Society

sincerely thanks

DR. ROMAN RADWAŃSKI

and

PROFESSOR JERZY MIZGALSKI

for their efforts in discovering this material and arranging to make it available for our website.

COPYRIGHT NOTICE:

Copyright of the original material contained on this page belongs to

BUNDESARCHIV in BERLIN

(German National Archive)

and

INSTYTUT PAMIĘCI NARODOWEJ (Institute of National Remembrance)

Copyright of the English language translations belongs to

ANDREW RAJCHER.

The material, on this page,

may NOT, either in part or as a whole, be copied, distributed or published without the prior written consent

of the copyright-holders.

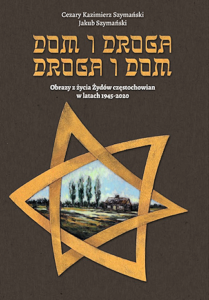

Home and the Road - the Road and Home

Home and the Road - the Road and Home

- a picture of the lives of Częstochowa Jews in 1945-2020

Dom i Droga – Droga i Dom, published in 2020, is the first synthetic work presenting an important and, at the same time, difficult research issue concerning the Jewish community in Częstochowa following World War II.

Dom i Droga – Droga i Dom, published in 2020, is the first synthetic work presenting an important and, at the same time, difficult research issue concerning the Jewish community in Częstochowa following World War II.

When Częstochowa was liberated on 17th January 1945, of the almost 30,000 pre-War Częstochowa Jews, 1,215 had survived. Much divided them, but one thing united them – a love for their home city. Their situation, due to the turmoil of history and politics was, for many years, extremely uncertain, especially in the context of the tragedy of the Kielce events in 1946 and, later, in March 1968 and the waves of emigration caused by it.

Against this background, the founding and activity, decades later, of the World Society of Częstochowa Jews and Their Descendants is an extraordinary phenomenon.

The contribution of Sigmund Rolat (a former prisoner in HASAG-Pelcery) is especially significant in the extensive restoration of the old cemetery and the commemoration of the time when Częstochowa Jews were transported to the extermination camp in Treblinka.

The symbols of the HOME (lost as a result of the Holocaust) and the ROAD (forced by the fate of emigration) intertwine, in a distinctive mosaic, overlapping within the subject of this well-written and broadly documented publication.

The authors present a pioneering and a long-awaited, by many, compendium of knowledge about the Jewish community of Częstochowa from 1945 to the present.

Click on any chapter heading icon to reveal text.

(The numbers in brackets, after each entry, correspond to the appropriate page numbers in the book.)

Authors:

Cezary Karzimierz Szymański

Cezary is the Director of ORION TV, the local Częstochowa television station.

For many years, he has been a strong and active supporter of our World Society and, through his television station, he has promoted all our Reunions, ongoing local Jewish community events and the Jewish community itself.

Jakub Szymański

Jakub is Cezary Szymański’s son and a practising lawyer in Częstochowa.

Since his teenage years, Jakub has taken an active interest in the Jewish history and legacy of his home city.

English translation:

Andrew Rajcher

IMPORTANT NOTICE

While this English translation is available for download, it may not, either in part or as a whole, be distributed or published without the prior written permission of Muzeum Częstochowskie and Andrew Rajcher, this English-language version copyright-holders.

Relevant Writings

Relevant Writings

by various authors

In this section of our website, we publish relevant research and academic papers, which we believe will be of interest to our website’s visitors.

In this section of our website, we publish relevant research and academic papers, which we believe will be of interest to our website’s visitors.

Papers will be listed here alphabetically by author.

Wherever possible, permission from the author is always sought prior to publication here.

(If you have any recommendations for the inclusion of additional material, please advise our Webmaster: aragorn@axiomcs.com.au).

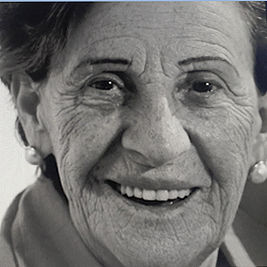

Jolanta Altman-Radwańska z"l

Jolanta Altman-Radwańska z”l

Jolanta Altman-Radwańska, following a long, debilitating disease, died on 18th January 2022 in Bonn on the Rhine. In her childhood and adolescence, she was involved with the Częstochowa branch of the Social-Cultural Association of Jews in Poland (TSKŻ).

Jolanta Altman-Radwańska, following a long, debilitating disease, died on 18th January 2022 in Bonn on the Rhine. In her childhood and adolescence, she was involved with the Częstochowa branch of the Social-Cultural Association of Jews in Poland (TSKŻ).

Her father was already a journalist by the inter-war period. He came from a well-known Jewish family, who had been associated with Częstochowa for over a century. Jolanta’s mother came from Lublin, from a patriotic, Polish, Catholic family.

In June 2020, she recorded her memories, filled with names and facts about the years spent in the TSKŻ. Asked to comment on these recordings, her husband, initially sketched her profile, attempting to recreate and understand her extremely interesting, though complex, identity.

Professionally, Jola graduated in history at the Śląsk University in Katowice (1976). Then for eleven years, she worked scientifically, including as the head of the Research Department at the Central Museum of Prisoners of War in Opole-Łambinowice. During those years, she established contacts with a group of several dozen former Polish officers from the World War II period, examining their fate as prisoners of war.

Professionally, Jola graduated in history at the Śląsk University in Katowice (1976). Then for eleven years, she worked scientifically, including as the head of the Research Department at the Central Museum of Prisoners of War in Opole-Łambinowice. During those years, she established contacts with a group of several dozen former Polish officers from the World War II period, examining their fate as prisoners of war.

Following the forced aggravated political situation in her country, she emigrated to Germany at the end of the 1980s. There, she resumed her work in the field in which she had begun. She continued collecting material for her doctoral dissertation at the University of Bonn, publishing numerous source articles on the fate of prisoners of war, as well as Polish, Ukrainian and Belarusian forced laborers in the Rhineland.

The network of contacts with this group of people, built up over the years, resulted in the organisation of several “Weeks of Meetings”, commissioned by the City of Bonn in the years 2000-2006. These was a strong media extraction and recalling of the difficult fate of these people during their forced stay in the city during the war years.

Submitted by:

Dr. Roman Radwański PhD.

English translation by

Andrew Rajcher

Post-War Abandoned Częstochowa Properties

Post-War Abandoned Częstochowa Properties

Presented, here, are scanned pages containing a listing of post-War, abandoned properties located in the city of Częstochowa.

This listing was prepared by the District Liquidation Office in Częstochowa, which operated from 1945 until 1951. The scans of this listing were obtained from the Polish State Archives in Kielce.

The Polish-language column headings, in English, are:

- L.p. = Line No.

- Ulica = Street [name]

- Numer domu = Building No.

- Rodzaj nieruchomości = Property Type

- Nazwisko i imię były właściciela = Surname & First Name of Former Owner

- Grupa = Group

- Reprywatyzowane = Reprivatised

- Przekazano Zarządowi Miejskiemu = Municipal Authority Notified

- Uwagi = Comments

Some other useful translations:

- i inni = and others

- dom = house

- plac = block of land

To search this listing by owner name,

click HERE.

Simply enter the surname at the top of the search engine.

The World Society sincerely thanks Daniel Kazez and the Częstochowa-Radomsko Area Research Group for making this listing and search engine available to us.

Please note: Some street names may have been changed since the time this list was created.

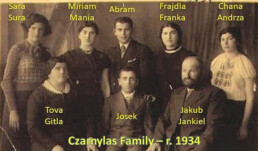

The Czarnylas Family

The Czarnylas Family

- a tribute to the maternal side of his family by Alon Goldman

The Czarnylas Family Before World War II

My mother was born on 1st April 1918 in Pajęczno, the sixth daughter of Jakub-Jankiel Czarnylas and Tova Gitla Czarnylas (née Rząśyńska).

Jakub-Jankiel Czarnylas, my grandfather, was also born in Pajęczno on 15th June 1886, to Icek Czarnylas and Frajdla Czarnylas (née Lipszyc), the fifth of their children.

From documents, which I found in the National Archives in Częstochowa, I learned that my grandfather Jakub-Jankiel had six brothers and sisters, who were all born in Pajęczno.:

Jakub-Jankiel, my grandfather, was born on 15th June 1886. His siblings were:

- Szandel, born 17th May 1873

- Abram, born 12th May 1875

- Esther, born 24th March 1878

- Hersz-Herszlik Fajbusz, born on 22nd January 1880

- Aron, born on 19th September 1882

- Nacha, born 1st May 1891

On 6th November 1908, my grandfather Jakub married Tova Gitla Rząśyńska, born 7th November 1886, in Pajęczno, the daughter of Gabriel and Mindla (née Buchman) Rząśyński.

I know nothing about the childhood of my grandparents and their family in Pajęczno, nor where they lived and what their parents did .

My great-grandfather Icek Czarnylas (my grandfather Jakub’s father) died at the advanced age of eighty-two in Pajęczno, on 16th February 1935 (Record No. 1/1935). he was buried in the local cemetery, of which no trace remained after World War II. From his death certificate, I learned that he was born in 1853 to Jakub-Jankiel Czarnylas and Sarah-Sura Czarnylas (née Bursztyn), both permanent residents of Pajęczno. I know nothing about my great-grandmother Frajdla-Freida (Icek’s wife) nor about when and where she died.

My grandparents, Jakub and Tova Gitla had seven children, all born in Pajęczno :

- Frajdla (Franka), born 16th February 1910

- Abram, born 14th November 1911

- Chana (Andrza), born 15th September 1914

- Bejnusz, born 1914, died 13th November 1915

- Miriam (Mania), born 13th December 1916

- Sarah-Sura, my mother, born 1st April 1918

- Joseph-Josek, born 20th April 1920

- Mosze, born July 1922, dec. 20th Sept. 1922

Due to the economic situation between 1920 and 1925, I do not know exactly when my grandfather Jakub and his family moved from Pajęczno to Częstochowa .

My grandfather Jakub was a successful businessman. He owned a sawmill, traded in lumber and, as well as other businesses. was a partner in a mirror manufacturing factory.

In Częstochowa, the Czarnylas family lived in a building owned by the family at ul. Katedralna 4, (on the corner of ul. Ogrodowa). In May 1939, together with two partners, Jakub Czarnylas purchased the building at ul Katedralna 8 in Częstochowa.

I know very little about my mother’s childhood in Czestochowa. Financially, the family was wealthy and lacked for nothing. A nanny lived with them, who took care of all their needs. Sara attended a high school for girl, and was a member of the Hashomer Hatzair Zionist youth movement. Her sisters, Mania and Franka, joined the Betar Zionist youth movement.

When she was 16 or 17 years old, she first met my father, Jerucham Goldman, who lived on the parallel street (at ul. Fabryczna 22 which, today, is ul. Mielczarskiego 22).

In 1933, her brother Abram immigrated to Israel in order to study at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

From research I carried out at the Pajęczno civil registry office, in the National Archives in Częstochowa and other places, I was able to find some information, in the period prior to World War II, about family members of my grandfather Jakub Czarnylas.

On 20th February 1893, in Pajeczno, his sister, Szandel Czarnylas, married Szaja Heller, who was born in Będzin on 23rd November 1869 and died on 10th September 1932.

In 1900, his sister, Esther Czarnylas, married Szlama Joskowicz, who was born in Będzin on 22nd November 1874. The couple had three children: Sarah born 23rd October 1902, Israel Lejbusz born 22nd April 1906 and Ruchla Frajdla born on 3rd October 1911. Esther and Szlama’s son, Israel Lejbusz married Ruchla Matla and, in 1934, they had a son David.

On 28th October 1903, in Pajeczno, my grandfather Jakub’s brother, Hersz-Herszlik Fajbusz Czarnylas, married Hanah Broda). Her family was also from Pajęczno and the couple had four children, all born in Pajęczno:

- Sara, born 28th October 1903

- Bejnusz, 10th April 1907 – 11th June 1910

- Miriam-Maria, born 30th June 1908

- Freida-Frajdela, born 28th September 1909

Hersz Fajbusz’ wife, Hanah, died on 21st January 1911 at the age of only twenty-eight. Two years later, on 22nd April 1913, Hersz Fajbusz married again, this time to Rebecca Minc of Zabkowice. This was also Rebecca’s second marriage. She had a son from her first marriage, Binem, who was born on 7th October 1907.

In Pajęczno, grandfather Jakub’s brother, Aron Czarnylas, married Chaja Ita née Abramowicz and, in Pajęczno, the couple had three children;

- Malka, born on 1st July 1900

- Frajdla, born on 8th May 1910

- Abram,born on 22nd May 1912

Grandfather Jakub’s sister, Nacha Czarnylas, married Jakub-Jankiel Lieberman, a merchant and one of the leaders of the Pajęczno Jewish community. In Pajeczno, the couple had eight children:

- Josef

- Isac

- Szmuel (Szmil)

- Frajdla born 24th June 1916

- Abram, born 10th March 1919

- Mosze Chaim, born 5th October 1921

- Aron, born 9th October 1922

- Meir, born 25th March 1925

The Holocaust

Luck did not play out for the Czarnylas family. On 3rd September 1939, Częstochowa was occupied by the Germans, who also occupied Pajęczno on 4th September 1939. From moment, the lives of the population, in general, and the Jewish population in particular, turned into Hell.

Shortly after the conquest of Częstochowa, in November 1939, my father said to my mother, “This will not end well and we must flee”.

Both, young and in their early twenties, were still unmarried. They came to their parents and offered to join them in escaping to the Russian side of the border, to Lwów, a city which my father had known from his electrical engineering internship, which he had completed just before the outbreak of the war. Their parents refused, claiming that the war would end soon and that there was no point in leaving Poland. In spite of everything, my parents decided to flee and, through difficult means, managed to escape to the Russian side of the border and to reach the city of Lwów. Grandfather Jakub Czarnylas tried to persuade them to return to Częstochowa and asked a rabbi to go on a mission to Russia to find them in Lwów and persuade them to return home to Częstochowa. The rabbi went to Lwów, met them and conveyed the message from their parents. He also gave them a sum of money which the parents had sent for them.

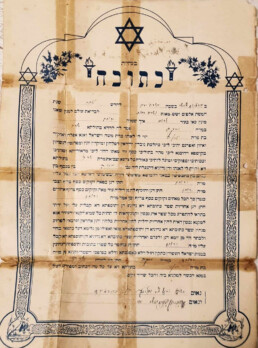

My parents, who were convinced that there was danger in Częstochowa, asked the rabbi to marry them in a Jewish ceremony. So, on 22nd December 1939, my parents were married in a Jewish wedding in Lwów. The rabbi returned to Częstochowa and informed their parents of their marriage.

In 1940, my father found work in a quarry and my mother also found temporary work which enabled them to survive. All the while, they were looking for ways to bring their parents to the Russian side of the border – but without success.

When the Germans invaded Russia in June 1941, my parents fled eastward towards Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan and, after some wandering, came to Tashkent and, from there ,to Samarkand.

In Samarkand, my father found a job in a beer factory. During his work, he fell ill. But, at that time, he could not afford to get sick and so he continued to work. It later turned out that, at that time, he had contracted tuberculosis. How he managed to overcome the disease no one knows .

Life in Russia was not easy to say the least. It was a Hell on Earth. In 1942, when word spread about the possibility that Anders’ Army (Polish Armed Forces in the East) would move westward outside Russia’s borders, my father took advantage of his profession as an electrical engineer and managed to enlist in Anders’ Army in the hope that he could leave Russia with the army .

After a long journey through Iran, Iraq and Lebanon, in May 1943, my father arrived in Mandatory Palestine (now Israel) with Anders’ Army.

My mother managed to leave Russia as the wife of a soldier in Anders’ Army and came to Mandatory Palestine with the Tehran children.

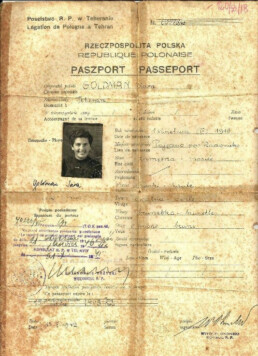

On her way to Palestine, in October 1942, the Polish consulate in Tehran issued her with a passport with which she was allowed to enter Mandatory Palestine .

Pic left: Passport, issued by the Polish consulate in Tehran on 15th October1942, in the name of Sara Goldman née Czarnylas.

In July 1943, Anders’ Army left Palestine for Egypt and, later, for North Africa, joining the Allied forces in Italy. At the end of the war, my parents met again in Palestine.

Arriving in Palestine, my mother met up with her brother Abram Czarnylas. At that time, he was the only family member known to have survived.

I do not know much about what happened to my family members who remained in Poland – in Pajęczno and in Częstochowa. I found the name of my grandfather Jakub Czarnylas on a list of forced labourers in the HASAG Pelcery forced labour camp in Częstochowa and, apparently, the rest of the family were also forced labourers in this factory, which manufactured ammunition for the German war effort.

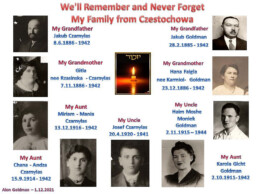

Almost the entirety of my mother’s family who remained in Częstochowa – her father Jakub, her mother Gitla and her sisters Miriam (Mania) and Hanah (Andrza) – found their deaths, during the liquidation of the “Big Ghetto” in September-October 1942, either in Częstochowa or in Treblinka.

According to testimonies from survivors, Jozef Czarnylas, my mother’s younger brother, was shot in the head by a German soldier in June 1941, when he lit a cigarette without permission while working at the Möbellager. This was a warehouse, on ul. Wilsona in Częstochowa, where the Germans stored furniture removed from Jewish homes in the ghetto.

Of the whole family, only one sister, Frajdla (Franka), survived the torment of the Holocaust. According to some documents, it seems that, for a certain period, she was in the Łódź ghetto, from where she returned to Częstochowa. From April 1940 until 16th January 1945, she toiled in HASAG Pelcery of Częstochowa. She was then sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, from where she was moved to the Burgau concentration camp, a sub-camp of Dachau. From there, she ended up in the Turkheim concentration camp, from where she was liberated on 27th April 1945.

Of the whole family, only one sister, Frajdla (Franka), survived the torment of the Holocaust. According to some documents, it seems that, for a certain period, she was in the Łódź ghetto, from where she returned to Częstochowa. From April 1940 until 16th January 1945, she toiled in HASAG Pelcery of Częstochowa. She was then sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, from where she was moved to the Burgau concentration camp, a sub-camp of Dachau. From there, she ended up in the Turkheim concentration camp, from where she was liberated on 27th April 1945.

Frajdla (Franka) was the only one of the whole family to return, after the end of the war, from the concentration camp to Częstochowa, only to see that no one from the Czarnylas family from Pajęczno and Częstochowa remained alive. As many did, Abram and Sarah in Israel and Frajdla (Franka) in Poland also began looking for survivors until they found each other. In 1948, Frajdla (Franka) left Poland and immigrated to Palestine to reunite with her brother and sister.

I was able to find very little information about the fate of the family members, brothers and sisters of my grandfather Jakub Czarnylas , who remained in Pajęczno.

During the German occupation, Jakub Lieberman, husband of Nacha Czarnylas (my grandfather’s sister) who was one of the leaders of the Pajęczno community, was appointed Chairman of the Judenrat. This was a thankless task, which required him to relate to all refugees from nearby villages and to supply the Germans with labour quotas.

From the beginning of the occupation, the Germans occasionally demanded work crews for camps in the Poznan area. More than once, the Judenrat succeeded in bribing German officials in order to cancel any deportation.

In 1941, the Pajęczno ghetto was established in the poorest part of the city.

Penalty taxes were repeatedly imposed upon the residents of the ghetto. The looting of Jewish property in the ghetto reached its peak in the spring of 1942, two weeks before Passover, when German police went from house to house, beating the residents, taking some as hostages and robbing them of their possessions. In the spring and summer of 1942, the Judenrat was required to hand over certain Jews to the Gestapo. In June 1942, the Chairman of the Judenrat, Jakub Lieberman was himself arrested along with eleven other Jews. They were all murdered by German policemen and, in their place, the Germans appointed the butcher Berl Mrówka to head the Judenrat. According to testimony given to Yad Vashem, Jakub Lieberman and other members of the Judenrat were taken to the Łódź ghetto, where they were executed by hanging.

The liquidation of the Pajęczno ghetto began on 19th August 1942. About 1,800 Jews of the ghetto were brought to a church and were held there for several days under extremely difficult conditions. During those days, another 140 Jews, who were found in hiding places in the ghetto, were forced to join them. On 21st August 1942, the Germans murdered all the elders in the churchyard, including Mrówka, the head of the Judenrat.

On 22nd August 1942, most of the Pajęczno Jews were deported to their deaths in the Chełmno extermination camp. The rest were sent to the Łódź ghetto. Of all the members of the Lieberman family, the only one to survive the Holocaust was Aron Lieberman. On 19th December 1939, he was imprisoned in Pajęczno, from where he moved about between concentration camps – to Monowitz, Fogenbord, Posen (Poznań), Buchenwald and Auschwitz.

Following his liberation in 1945, in a chance meeting with one of his townspeople, he realised that none of his family members had survived the Holocaust and so he had no reason to return to Pajęczno.

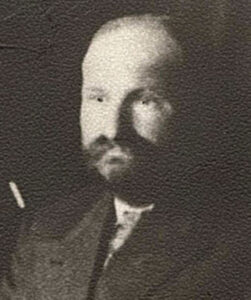

Pic below: Aron Lieberman’s ex-concentration camp identity card

Life After the Holocaust

Adapting to life in Israel was not easy for my parents, both in terms of housing and work. They had to cope with a new place, a new language and a difficult economic situation in those first years. On 9th July 1948, my older brother was born and was named Jacob, after his two grandfathers, who perished in the Holocaust. After his birth, my parents bought a three-room apartment in Ramat Gan, where they lived all their lives. I was born in this home on 8th August 1953 .

My father Jerucham began his career in Israel with occasional jobs in the electrical field. At one time, he ran a garage specialising in automobile electronics, until he found employment, in large factories, in his profession as an electrical engineer. In 1958, he was appointed Chief Electrical and Maintenance Engineer of the Beilinson Hospital, the biggest hospital in Israel. He worked until he retired in 1986. After retiring, he continued to work for several more years as a consultant to a network of nursing homes and a private hospital in Bnei Brak.

My father Jerucham began his career in Israel with occasional jobs in the electrical field. At one time, he ran a garage specialising in automobile electronics, until he found employment, in large factories, in his profession as an electrical engineer. In 1958, he was appointed Chief Electrical and Maintenance Engineer of the Beilinson Hospital, the biggest hospital in Israel. He worked until he retired in 1986. After retiring, he continued to work for several more years as a consultant to a network of nursing homes and a private hospital in Bnei Brak.

All those years, my mother was a housewife and, when my brother and I were already grown up, she operated a sewing shop in a large textile chain in Israel.

My parents were very happy when they saw the establishment of the next generation of the Czarnylas and Goldman families in Israel. My brother Jacob married Yehudit (née Mendelson) on 13th October 1971. They have two daughters, Liat and Karen, and four grandchildren. I married Dorit (née Sussman) on 16th October 1986. We have three daughters – Tal, Dana and Noa and currently three granddaughters.

My mother, Sarah Goldman (née Czarnylas), passed away on 8th October 1988 and my father Jerucham Goldman passed away on 1st December 2000.

Frajdla (Franka) (née Czarnylas), after immigrating from Poland to Israel, lived in Tel Aviv. She first married in 1950, a marriage that did not last. In 1957 she remarried. Throughout her life, she suffered greatly from health problems caused by everything which she had gone through in the concentration camps. She had no children. She died in Tel Aviv on 10th March 1978.

Abram Czarnylas, who came to Israel as a student, married Esther (née Ha’Ivri). They had three children – Prof. Josef Czarnylas (a cardiologist, named after his uncle, who was shot to death in Częstochowa), Nira and Nava. They have eight grandchildren and fourteen great-grandchildren. Abram was a businessman in the field of building materials and real estate. He died of a heart attack in Israel on 24th December 1960, at the age of only forty-nine.

Abram Czarnylas, who came to Israel as a student, married Esther (née Ha’Ivri). They had three children – Prof. Josef Czarnylas (a cardiologist, named after his uncle, who was shot to death in Częstochowa), Nira and Nava. They have eight grandchildren and fourteen great-grandchildren. Abram was a businessman in the field of building materials and real estate. He died of a heart attack in Israel on 24th December 1960, at the age of only forty-nine.

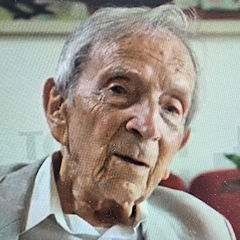

Aron Lieberman (son of Nacha Lieberman – née Czarnylas) was the only survivor of his family. After being released from Auschwitz and, after a chance meeting with his townspeople in a displaced persons camp, he realised that no one from his family was alive and so he went to Eindhoven, in the Netherlands. There, he was adopted by a Dutch family and found a job at Philips Electric. In 1954, he came to Winnipeg, Canada, and, in 1958, he married Dora Wise. Aron had two sons, Jeffrey and Gary, and five grandchildren. After searching for several years, the cousins Aron, Sarah, Abram and Freidla (Franka) found each other. In October 2021, he celebrated his 99th birthday.

Aron Lieberman (son of Nacha Lieberman – née Czarnylas) was the only survivor of his family. After being released from Auschwitz and, after a chance meeting with his townspeople in a displaced persons camp, he realised that no one from his family was alive and so he went to Eindhoven, in the Netherlands. There, he was adopted by a Dutch family and found a job at Philips Electric. In 1954, he came to Winnipeg, Canada, and, in 1958, he married Dora Wise. Aron had two sons, Jeffrey and Gary, and five grandchildren. After searching for several years, the cousins Aron, Sarah, Abram and Freidla (Franka) found each other. In October 2021, he celebrated his 99th birthday.

All these years, we have lived in the knowledge that, with the exception of the four, Abram Carnylas, Freidla-Franka (née Czarnylas), Sarah GOLDMAN ( née Czarnylas) and Aron Lieberman, all the other members of the Czarnylas family perished in the Holocaust.

Complete and Unfinished

In 2014, during one of my visits to Poland, I met Ms. Anna Przybyszewska, from the Genealogy Department of The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw, in order to try to find more information about my Czarnylas family members from Poland. Unfortunately, at this meeting, no new information was revealed.

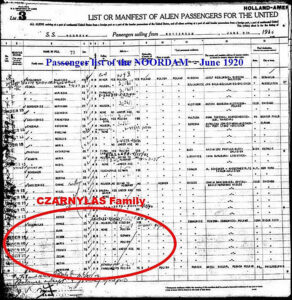

However, a big surprise awaited me in early 2015, seventy years after the end of World War II. I received an email from Anna Przybyszewska in which she wrote that she had come across a passenger list from a ship called the Noordam, which had arrived, on 9th June 1920, at Ellis Island in the United States from Rotterdam in the Netherlands. One of the passengers on this ship’s manifest was Rebecca Czarnylas (aged thirty-five). She was a native of Zabkowice, who had lived in Pajęczno and had arrived with six children – Sarah (aged 17), Binem (13), Maria (11), Frania (10), Zelma (8) and Motka (7). Her husband, Harry Lass, a baker, who lived at 603 Iowa St., Sioux City, Iowa, was waiting for her on the platform, and he was the one who paid for the passage.

However, a big surprise awaited me in early 2015, seventy years after the end of World War II. I received an email from Anna Przybyszewska in which she wrote that she had come across a passenger list from a ship called the Noordam, which had arrived, on 9th June 1920, at Ellis Island in the United States from Rotterdam in the Netherlands. One of the passengers on this ship’s manifest was Rebecca Czarnylas (aged thirty-five). She was a native of Zabkowice, who had lived in Pajęczno and had arrived with six children – Sarah (aged 17), Binem (13), Maria (11), Frania (10), Zelma (8) and Motka (7). Her husband, Harry Lass, a baker, who lived at 603 Iowa St., Sioux City, Iowa, was waiting for her on the platform, and he was the one who paid for the passage.

Another look at Ellis Island’s website, of records of entry to the US, yielded another surprise. On the passenger list of that same ship, the Noordam, arriving in the USA from Rotterdam on 29th October 1920, was Hanah Czarnylas (35) from Pajęczno. She appears with with three children – Malka (aged 18), Frida/Trailo (11) and Abram (9). Her husband, Archie Lass, a baker, who lived at the same address as Harry Lass, 603 Iowa St., Sioux City, Iowa, is also listed as waiting for her on the platform and he also paid for the family’s trip.

Are Harry Lass and Archie Lass, brothers of the Czarnylas family from Pajęczno? Is Harry Lass perhaps Hersz Fajbusz Czarnylas and is Archie Lass perhaps Aron Czarnylas, the brothers of my grandfather Jakub Czarnylas?

In an attempt to solve the mystery, I went back to check the certificates (birth, marriage) of Czarnylas family members from the National Archives in Częstochowa. Given that the passenger list records the age of the passengers when arriving in the United States, together with the place of birth and husband’s occupation, I reasoned that we could compare the details and then determine if the immigrants to the USA were possible family.

From the examination of the documents in my possession, I understood very quickly that the three children (Sarah, Maria and Frania), who came with Rebecca, WERE the children of Hersz Fajbusz Czarnylas, from his marriage to Hana Broda, and that Malka, Frida and Abram were the children of Aron Czarnylas from his marriage to Hana Ita Abramowicz.

I also discovered that Hana Czarnylas (nee Broda) had died in Pajęczno on 21st March 1911 and that Hersz Fajbusz Czarnylas remarried Rebecca Minc of Zabkowice on 13th April 1913. (She was the woman who came to the United States with the children.)

But who were the other three children on the list who came with Rebecca? How do I verify beyond any doubt that Harry and Archie are the brothers of my grandfather Jakub Czarnylas?

My search on the JewishGen website led me to Katherine Lass from St. Louis, USA, who was looking for information about the Czarnylas from Zabkowice. I contacted her and, after an email exchange and phone calls, the mystery was solved. She told me that Binem (one of the children) was Rebecca’s son from her first marriage and was Katherine’s father. According to what Binem had told Katherine, they were from a small town in Poland and that their family name in Poland was “Black Forest” which, in Polish, is “Czarnylas”. Katherine’s grandmother Rebecca was from the Minc family and Zalma (Sam) and Motke (Max) were children born from Rebecca’s marriage to Harry. In response to my question if she had contact with the rest of the family, she answered that she had no contact, but knew that one cousin, Kenneth Lass, was living in Nashville, Tennessee.

My search on the JewishGen website led me to Katherine Lass from St. Louis, USA, who was looking for information about the Czarnylas from Zabkowice. I contacted her and, after an email exchange and phone calls, the mystery was solved. She told me that Binem (one of the children) was Rebecca’s son from her first marriage and was Katherine’s father. According to what Binem had told Katherine, they were from a small town in Poland and that their family name in Poland was “Black Forest” which, in Polish, is “Czarnylas”. Katherine’s grandmother Rebecca was from the Minc family and Zalma (Sam) and Motke (Max) were children born from Rebecca’s marriage to Harry. In response to my question if she had contact with the rest of the family, she answered that she had no contact, but knew that one cousin, Kenneth Lass, was living in Nashville, Tennessee.

According to Jewish tradition, it is customary to write the Hebrew name and the father’s Hebrew name on a person’s cemetery gravestone. On the one hand, I have the Polish documents with the Hebrew names that were used in Poland but, on the other hand, I have the names that were often written incorrectly when arriving in the US, along with the new names which they adopted. In order to further my investigation, I had the idea to try to locate the burial places of Harry and Archie and to see what is written on their gravestones, and whether the name of their father Isac appears on their gravestones.

My efforts bore fruit and in the Independent Farane Jewish cemetery in Sioux City, Iowa, I found their graves. With the help of Ms. Rhonda Menin, the cemetery director, I obtained pictures of the three graves:

Harry P. Lass – died 7th March 1952 – Section A, Grave 1411

On his tombstone, written in Hebrew, is Zvi Hersz son of Isac/Yitzchak, next to the name Harry, the name which he adopted in the USA. Zvi is Hersz, so Harry’s Hebrew name, year of birth and father’s name matched the documents from Poland.

Harry’s wife Rebecca Lass – died 23rd May 1958 – Section A, Grave 1412

Rebecca’s father’s name, David, which appears on the tombstone, is the same as her father’s name which appears on her marriage certificate to Hersz Fajbusz (Harry) from Poland .

Archie Lass – died 4th November 1941 – Section A, Grave 1414

On his tombstone is written, in Hebrew, Aron son of Isac/Yitzchak Lass.

Exactly when Hersz Fajbusz and Aron, my grandfather’s older brothers, immigrated to the United States, I do not know.

My mother never talked about family in the USA and I guess, until the day she died, she did not know about all of it. So all these years we lived thinking that the whole Czarnylas family had perished in the Holocaust. In my estimation, they left for the USA sometime after 1913 and, after establishing themselves, in 1920, they brought their wives and children.

Thanks to difficult genealogical research, I found some of the Czarnylas descendants all over the United States in such places as Dallas, Houston, El Paso, Plano, Chicago, Springfield, Nashville, Beverly Hills and Los Angeles.

When I contacted them, it was a huge surprise and big shock for them – the discovery of an unknown chapter in their family history which begins in Pajęczno in Poland, about which they knew nothing.

This is where my story ends – the story of the Czarnylas family from Pajęczno and Częstochowa, Poland. I do not know everything and there are many things which I will never know .

Webmaster’s Comment:

The contents on this page,

about the maternal side of his family

has been supplied by

Alon Goldman,

Chairman of the

Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel,

Vice-President of the World Society of Częstochowa Jews & Their Descendants.

Below, he writes a little about himself:

As in many homes of Holocaust survivors, in my home, my parents hardly talked at all about the Holocaust. In fact, we, the second generation, were not so interested in the subject.

As a child, at home, I spoke to my parents in Polish as a first language, which I had learned from my mother and father naturally (a language I speak to this day, even though I never formally learned it in school and which I call “Intuitive Polish”, because I can’t explain why I say things the way I say them).

We lived in our world, as Israelis proud of the free State of Israel, and facing the needs for its existence, seeing as how it is surrounded by Arab countries wishing to destroy it.

Like most youth in Israel, I grew up in a modest home. At the age of 18, I completed my high school education and, in 1972, I enlisted in the Israeli army like most Israeli youth. During the Yom Kippur War in 1973, I served as an officer in the 401 Tank Brigade in Sinai and, after my release from regular service, I continued in the reserve service for many years, from which I was discharged with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel.

At the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, I studied for a Bachelor’s Degree in Economics and, at Tel Aviv University, I completed a Master’s Degree in Business Administration. Concurrently with my studies, I worked at Bank Leumi, where I was promoted to very senior management positions.

When my mother passed away in 1988, I suddenly realised that I knew almost nothing about my roots and that I also had no one to ask, since almost her entire family perished in the Holocaust and those of her family members, who survived, had already passed away.

This was the beginning of my journey to discover my roots and identify as part of the heritage left to me by my father and mother. The journey continued in earnest several years later.

In 2006, I was invited to join the Association of Częstochowa Jews in Israel. In 2011, I was elected Chairman of the Association and then also to the office of Vice-President of The World Society of Częstochowa Jews and Their Descendants.

During this time, my ties with Poland have strengthened and so the journey to discover my roots has intensified .

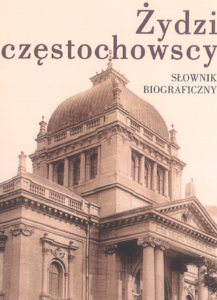

Częstochowa Jews - a Biographical Dictionary

Częstochowa Jews - a Biographical Dictionary

- edited by Dr. Juliusz Sętkowski

This book contains almost 600 biographies of Jews, who were associated with Częstochowa in the 19th, 20th and early 21st centuries. It includes those who were born and lived permanently in Częstochowa, as well as those who were associated with the city for a short period or even for several years.

What determined their inclusion in the publication was their professional and creative activity or social service within the community. Some of the distinguished individuals in this dictionary were born in Częstochowa, but left at a young age and their contributions became well-known elsewhere – in Israel and abroad.

Included are profiles of Jews who were significant in the history of the city and the state. They include the names of Jews active in the economic, political, local, social, religious and scientific fields, as well as in education, health, law, sports, culture and art.

This book is the result of research by many people over many years – in archives, published bibliographies and press reports – as well as efforts to obtain information directly from families. The work makes extensive use of necrology, documenting information about deceased people, as well as broader memories describing the activities of a given person. Much information was taken from inscriptions engraved on the cemetery tombstones. The book makes use of the extensive material contained in the first volume of the cemetery book by Wiesław Paszkowski, “The Jewish Cemetery in Częstochowa”, which was published in Częstochowa in 2012.